Analysis by Keith Rankin.

- Representative Democracy

On 26 June, I attended a zoom webinar called ‘Modern politics – 20thC to MMP’, run by Auckland Libraries and Ancestry.com. The speakers were politics’ academics Grant Duncan and Toby Boraman, from Massey University. Duncan is a well-known political scientist, and Boraman is a specialist in Labour History. (An edited recording of the webinar will become available via Auckland Libraries, at some time.)

My first main ‘takeaway’ from the webinar was Grant Duncan’s observation that – since the advent of multiparty proportional representation in New Zealand – while there has been much more gender, religious and ethnic diversity among MPs, the parliament as a whole is increasingly ‘middle class’. Re gender, faith and ethnicity, this change has clearly been accelerated by the 1990s’ advent of proportional representation. Re ‘class’, the change clearly began in the 1980s with the bourgeoisisation of the Labour Party and its voter base. (Today the ‘salariat’ substantially votes Labour, and the ‘precariat’ is fertile political territory for National. Possibly the average income of Labour voters now exceeds the average income of National voters.)

The major implication of this is that Parliament in general – and Labour in particular – is overwhelmingly ‘socially liberal’ but ‘economically conservative’. Further, the journalism profession tends to follow the same socio-economic profile as parliament. It means that whatever new economic problems arise, thinking that may address those problems suffers constant and intellectually lazy pushback. And, within the catchphrase ‘economically conservative’, we may read ‘financially ultra-conservative’.

My second takeaway arose from a question asked of Toby Boraman, who presented a standard left-wing account of the rise of poverty and inequality in New Zealand. A question from the floor was: “What do you think of Universal Basic Income?”. The answer given was that UBI covers a whole spectrum of proposals. On the extreme right, Boraman said, are the minimalist proposals which offer a relatively small amount to all adults in place of all other welfare benefits. This would aggravate inequality. On the extreme left, he said, were proposals to pay a universal benefit equivalent to a living weekly wage; this would be very expensive and would be far from the best way to spend that amount of money.

Boraman, having dismissed the extremes, then dismissed the whole UBI concept without any mention of the practical centrist versions. He went on to argue for an anti-poverty program along the lines of that recently announced by the Green Party. He argued for benefit levels to be substantially raised, and for marginal rates of income tax on high earners to be raised likewise. Thus, he wished to create a left-wing version of the redistributive welfare state. I note here that the redistributive welfare state supplanted the universal welfare state in New Zealand after 1985, under the auspices of ‘Rogernomics’. Welfare targeting in New Zealand took on its present distinctly right-wing form in 1988 (the movement to low marginal tax rates) and in 1991 with the cuts to welfare benefits and the Employment Contracts Act.

It is less than academically honest to dismiss a concept by dismissing the most extreme examples of that concept; it is even less honest when the extreme examples cited do not properly reflect the concept that is supposedly being dismissed. Likewise, it is less than honest to advocate a strengthening of the existing redistributive mechanism and call the result ‘reform’. The redistributive welfare state attempts to transfer income from the people at top of the income spectrum to people who are not employed. Increasing the scale of existing transfers is not ‘reform’. And the retention of means-testing systems which dehumanise those in need of income support is not reform either.

- Universal Basic Income – Public Equity Dividend

The universal basic income moves income tax and benefit policy in the opposite direction from that of redistributive proposals. It’s a distributive mechanism, not redistribution. And, as with the right to vote, it directly applies to adults only. It’s a democratic mechanism.

When I first used the name ‘universal basic income’ in 1991, I wrote about a mechanism, not an unfunded benefit. Since that time – especially in the twenty-first century – the name ‘universal basic income’ has come to mean, in the public mind, an unconditional universal benefit divorced from any specific funding mechanism. So, I tend not to use the name ‘universal basic income’ so much these days, except in a very general sense. I prefer universal income flat tax (UIFT) when referring to the mechanism and public equity dividend when referring to the specific benefit proposed.

The mechanism is, firstly, to take the top marginal income tax rate (33% in New Zealand) – or for countries with a top marginal rate above 40%, take the highest rate that is not above 40% (eg 37% in Australia) – and tax all market income at that rate. In New Zealand, this would mean that taxpayers earning $70,000 or more per year would incur $9,080 more in income tax ($175 more each week) than they do now. Then, secondly, every economic citizen (of New Zealand, for example) would receive an annual public equity dividend of $9,080 (payable weekly at $175 per week or fortnightly at $350).

This means that all persons presently earning $70,000 or more per year would experience no change to their disposable incomes (ie incomes after deduction of taxes and addition of benefits). These people – persons earning $70,000 or morewhom for present purposes we call ‘high income’ people – benefit, however, by knowing that they would retain their $9,080 dividend if their annual income falls below $70,000.

At the low end of the income spectrum we have people who can be called ‘beneficiaries’: public beneficiaries, private beneficiaries, and hybrid beneficiaries. Public beneficiaries in New Zealand receive cash ‘transfers’ from the Ministry of Social Development (MSD), and/or ‘family tax credits’ tax credits from the Inland Revenue Department (IRD). Private beneficiaries are fully supported by other family members, child support payments, and/or student loan living allowances. Hybrid beneficiaries receive a mix of public and private support, with (in the New Zealand example) their public income support being less than $175 per week.

For current public beneficiaries in New Zealand, under the universal income flat taxmechanism the first $175 per week becomes their public equity dividend. (The remainder of their present benefit becomes a means-tested supplement.) Thus, public beneficiaries neither gain nor lose. However, when their circumstances change, they retain their public equity dividends. These people – public beneficiaries – may be categorised as ‘low income’. Persons who by these definitions are neither ‘high income’ nor ‘low income’ can be called ‘medium income’. Thus, for our purposes, economic citizens fall into one of three categories.

The universal income flat tax mechanism has been fully described for New Zealand in the short third paragraph of this section. Anything else tagged onto a specific universal basic income proposal is exactly that, something else. Thus, the removal of existing public benefits is not a part of the universal income flat tax concept. Nor is any proposal to raise other taxes or introduce new taxes a part of the core concept. Such conjoint proposals, if advocated by some writers, remain secondary proposals and should be critiqued separately. (While some additions tagged onto a universal basic income proposal may be worthy policies, they need to be part of a separate discussion, and should not deflect attention from the core concept.)

(Two points to note. First, as defined, some New Zealand Superannuitants may find themselves, as public beneficiaries, defined as both ‘low income’ and ‘high income’ earners. There is an argument that high-earning public superannuitants should be worse off than they are at present. That argument is addressed in my Universal Dividends and Universal Superannuation. Second, given the housing crisis and the paltry state of housing subsidies in New Zealand, payments made by MSD under the rubric ‘Accommodation Supplement’ should probably not be classed as public benefits.)

- Equity and the Three Income Categories

In the above section, I have defined ‘high income’, ‘low income’ and ‘medium income’ economic citizens. Under the UIFT mechanism, ‘high income’ and ‘low income’ people neither lose nor gain disposable income. However, both groups stand to gain if changing circumstances take them into the ‘medium income’ group. In effect, both high and low income recipients already receive public equity dividends.

The targeted redistributive welfare state largely ignores the ‘medium income’ group, making this a financially insecure group. The most insecure of these people represent the ‘cracks’ in targeted welfare, the most mistreated people at present. It is the poverty trap created by conditional and means-tested welfare that strongly discourages people from moving out of ‘low income’ status. In the case of the Green Party version of redistributive welfare, the poverty trap becomes a ‘ghetto trap’; less poverty, more trap.

Rights-based public equity dividends practically target the insecure ‘middle income’ group. By definition, all people in this group gain; although for many the gains will be small. The bigger gain for many will be the security of the equity dividend. This represents a second income stream, a component of personal income that is not diminished when a worker’s weekly wages fall.

Under the pure UIFT proposal, how can we afford benefits that stop financially insecure people falling through the ‘welfare cracks’? Under normal circumstances – for example, a growing economy as in January 2020 – many adults in New Zealand are in or close to the ‘high income’ category. There are minimal additional financial costs associated with their public equity dividends. Further, most people in the ‘low income’ category are there for reasons other than unemployment, so there will be many of these people, even in a strong economy. Their incomes are unaffected.

The remaining ‘middle income’ group can gain higher government-sourced payments in lieu of a traditional pre-election round of tax cuts or benefit increases. In other words, this would be tantamount to a ‘tax cut benefit increase’ policy that targets the ‘medium income’ group rather than the ‘high income’ or ‘low income’ groups who are normally targeted.

Other economies arise. The administration deadweight costs for a universal dividend are substantially lower than for a redistributive process. And there are few opportunities for economically inefficient ‘moral hazard’ behaviours such as tax avoidance. Further, many people – especially young single people – once receiving a public equity dividend may still qualify for a small additional benefit. But they may choose to get on with their private lives rather than incurring time-costs engaging with the Ministry of Social Development. The Ministry would both downsize and focus on the people whose needs cannot be met through a combination of wages and equity dividends.

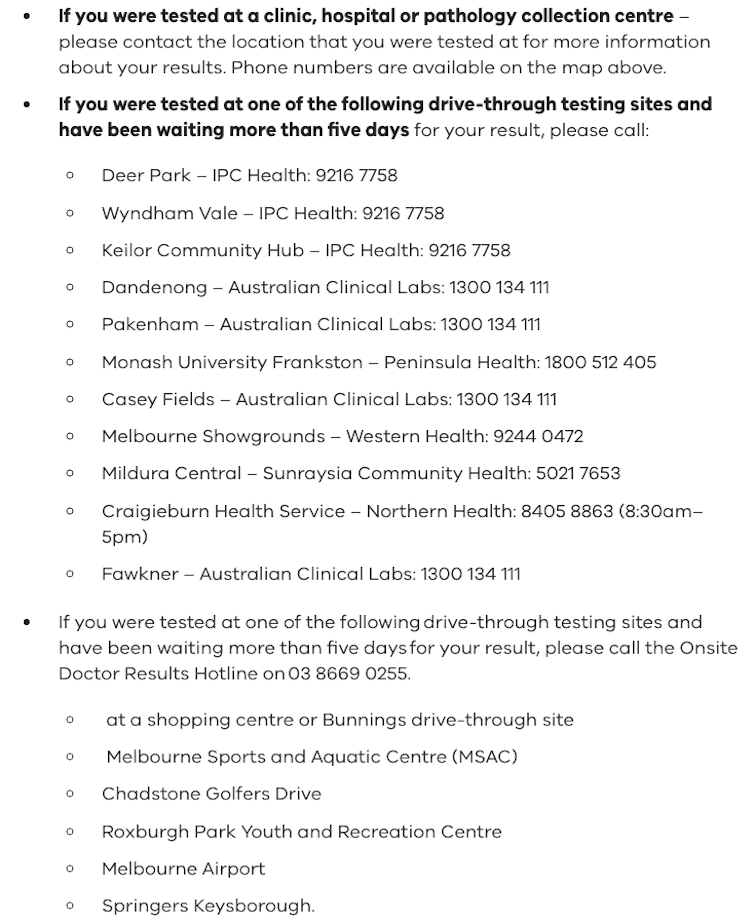

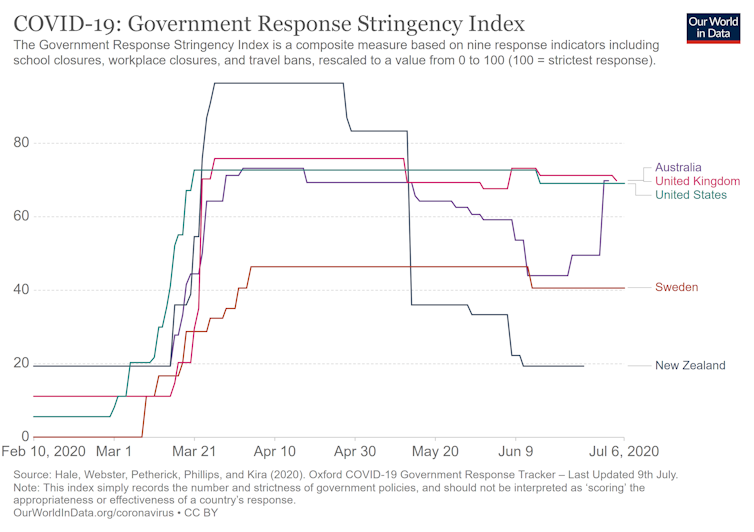

In situations of public health emergency – such as the present Covid19 crisis – there will be many more people falling into in the ‘middle income’ category, and falling within that income category. The total contribution of public equity dividends to household budgets would be higher at such a time; a time when total taxable income is lower than usual. During such times, economies cannot function without substantial deficit funding – the creation of new money which we owe to ourselves. The funding requirements of a public equity dividend during such a crisis are neither higher nor lower than the requirements of any alternative support mechanism. Universal income flat tax represents the most efficient automatic stabilisation mechanism available; a mechanism that minimises job losses in a recession and inflation in an overheated economy.

- Children

The universal income flat tax mechanism itself says nothing about children. We may note, however, that financially secure parents are best placed to care for their children. (The key idea is that of the aeroplane oxygen mask; parents must be supported first, in order that they may best care for their children.)

The UIFT concept – as applied to New Zealand – would ensure that all caregivers would receive at least $175 per week of publicly sourced income. Those caregivers already receiving more than that – for example, caregivers of large families – would continue to receive what they already receive.

It may well be desirable to return New Zealand to a system of universal family benefits – that is, as existed in New Zealand from 1946 to 1986, universal benefits paid to caregivers on behalf of all children. This is what some people call a universal basic income for children. With an adult universal basic income (aka public equity dividend) paid to all caregivers, the need to additionally pay child universal benefits to caregivers is not so clear. It may be that the additional cost of universal chid benefits is not worth the additional benefit.

- The Opportunities Party (TOP)

Last week I spoke at a public meeting organised by The Opportunities Party. TOP’s principal policy is a universal basic income; further, TOP’s proposal is pitched to the political centre rather than to left-wing or right-wing voters.

The other invited speakers were Sue Bradford (former Green Party MP) for a left-wing version of UBI, and Don Brash (former leader of National and Act) for a right-wing version. Unfortunately, Bradford had to send her apologies at the last minute. Don Brash, in his short presentation, gave the classic right-wing version. He was looking at a UBI of $9,000 per year and an income tax rate of 30%. (Compare the $9,080 and 33% in the above discussion.) What made Brash’s version distinctly right-wing was his assertion that “logically”, once a UBI was in place there would be no need for other benefits.

I could see no logic in Don Brash’s ‘logic’. While all UBI proposals emphasise rights-based ‘horizontal equity’ over needs-based ‘vertical equity’, redistributive welfare is underpinned by vertical equity principles. The Brash UBI is based solely on horizontal equity principles. I can see no logical reason why all forms of needs-based income support should be abandoned once a rights-based mechanism is introduced. This desire by Don Brash to remove needs-based benefits is the reason why his proposal is not politically viable, easily able to be picked off by sceptics.

Extreme left-wing proposals also deemphasise needs-based supports. Instead they tend to advocate a universal benefit that is high enough for people with divergent needs to live something like a normal life without any market-sourced income (eg without needing wages); it’s a one large size fits all approach. These left-wing versions usually advocate large wealth taxes to pay for the high level of universal benefit.

Such left-wing versions are not politically viable because of the spectre of high taxes (with ‘big government’ connotations), and, especially, because they lack an ‘incentive to work’. Enough people believe that many other people will only contribute economically to their society if coerced to via an implicit threat of poverty; enough people think like this to render an overly generous UBI politically non-viable.

In general, if a policy concept is good, it should not be presented with politically non-viable add-ons. Further, too much change in one single policy sweep – the big-bang policy approach – should be understood as politically non-viable. It means that any UBI policy on offer should stick to the core concepts, and should pay an initial public equity dividend that is seen to be inadequate as a sole income; seen as complementary to market income rather than as an alternative to market income. Set initially at modest levels, public equity dividends free people to seek employment – including precarious employment and risky self-employment – rather than encourage people to become employment-averse.

What of the TOP proposal? It is a good policy, based on the core concepts, and very much pitched at the political centre. A particularly important theme of TOP’s universal basic income policy is that people should not have their economic rights curtailed on account of personal relationships formed. Any liberal policy should emphasise individual rights, while also facilitating shared initiatives.

There are three main points of difference to note between TOP’s policy, and the core concept outlined here:

- The TOP dividend is $13,000 ($250 per week). Thus, it requires additional funding. A form of wealth tax on real estate is proposed. The policy can be understood as a core dividend of $175 per week funded by income tax, plus an extra $75 per week funded by other means. Thus, any critique of the ‘other means’ of funding – the proposed wealth tax – should apply only to the extra $75 of the proposed weekly dividend.

- The TOP proposal pays, additionally to adult dividends, a $40 child dividend, 16% of the adult dividend. This may be an unnecessary complication, which muddies the concept of economic citizenship. Is a child 16% of an economic citizen? It means that a non-employed caregiver in a two-parent family – a traditional homemaker/caregiver – would receive at least $250 per week plus $40 per child. While some additional funding may be required for this, in practice many recipients of these payments would already be getting as much through Family Tax Credits.

- While TOP plans to keep paying traditional benefits (as ‘top-ups’) to people whose benefit entitlement would exceed the dividend, they also talk of closing the Work and Income section of the Ministry of Social Development, the agency that presently pays most benefits. TOP could be more clear about who instead would pay such benefits. It seems to me that one agency – maybe a new agency – could manage and pay all supplementary benefits, including ‘top-up’ family tax credits. This agency should not be Inland Revenue (IRD); the IRD should not hold any information about clients’ personal relationships.

- Finally

Once a public equity dividend – based on core universal income flat tax principles – is in place, then any other mechanism would seem to be ridiculously inefficient. Once such a mechanism is in place, then right-wing political parties would tend to favour lower public equity dividends coupled with a lower income tax rate. And left-wing political parties would tend to favour higher equity dividends with a higher income tax rate. More precariously employed people would tend to vote left; and people with more established and reliable incomes would tend to vote for right-wing parties. (Politics of course would be much wider than this! Politics would still be politics.)

This would see a reversal of the trends to political representation shown by Grant Duncan. The political left would once again become the side of politics that represents the financially insecure.

Further, if labour becomes increasingly automated – done more by mechanical slaves than by people – then the ensuing problem of income maldistribution would be practically resolved by regular incremental increases to both public equity dividends and the income tax rate.

Likewise, a need for growth to slow down to save the planet from environmental distress could also be addressed by incrementally higher public equity dividends. Employed and self-employed people would be encouraged to gradually reduce their labour supply, raising productivity, and maybe producing a bit less and buying a bit less.