Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mehmet Aslan, Honorary Fellow, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong

Australian universities are expected to lose billions of dollars in revenue due to the impacts of COVID-19. The estimated lost revenue from international students alone is A$18 billion by 2024. While all universities are affected, regional universities and communities are the most vulnerable.

Regional communities have limited resources, so their universities play a pivotal role in their economies. These universities must adjust to the rapidly changing circumstances and government policy changes, or risk jeopardising regional economic growth and jobs. Without targeted government support for these smaller universities, the long-term impacts on regional communities could be devastating.

The Regional Universities Network (RUN) includes CQUniversity, Southern Cross University, Federation University Australia, University of New England, University of Southern Queensland, University of the Sunshine Coast and Charles Sturt University. CQUniversity, where 39% of students are international students, has a revenue shortfall of A$116 million for 2020. Charles Sturt University (32% international students) faces a loss of about A$80 million.

Read more: COVID-19: what Australian universities can do to recover from the loss of international student fees

What are the regional economic impacts?

All universities face job losses as a result of COVID-19. But the impacts of these job losses are greatest for regional economies.

RUN chair Helen Bartlett told a federal parliamentary committee hearing in May:

Job losses from regional universities have a significant impact on regional communities when there are few alternatives for professional employment locally.

She called on the government to double the annual regional loading funding of A$74 million.

Regional universities educate around 115,000 students each year. That’s about 9% of enrolments at Australian public universities.

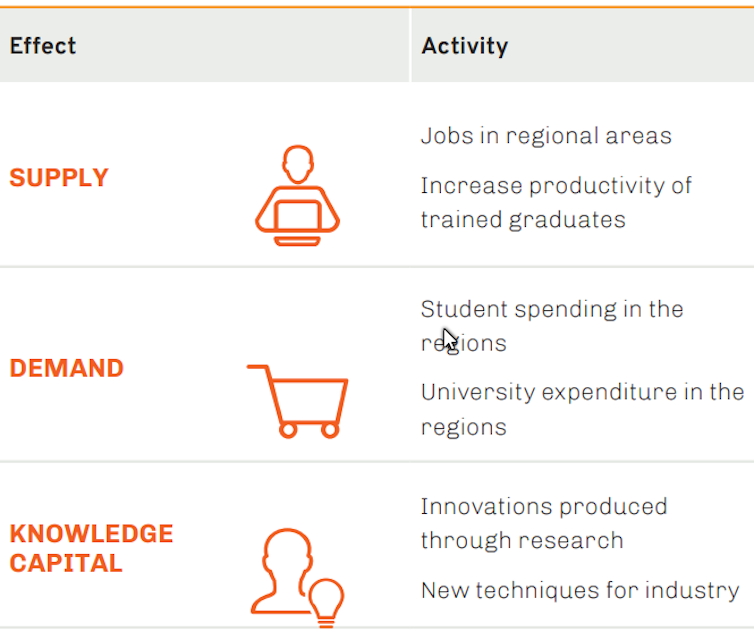

A 2018 study found regional universities inject A$1.7 billion a year into their local economies. And seven out of ten graduates go on to work in regional areas.

Regional universities also contribute over A$2.1 billion and more than 14,000 full-time jobs to the national economy.

What is the government doing?

In April the federal government guaranteed A$18 billion in university funding this year to help the sector through the coronavirus crisis. It also provided A$100 million in regulatory fee relief.

The chair of Universities Australia, Deborah Terry, welcomed this as a “first step”. However, she warned an estimated 21,000 jobs would still be lost.

In June, the government announced the Job-ready Graduates Package. It plans to lower student fees for selected courses (and raise others) to encourage study for what the government deems to be jobs of the future.

Extra support announced for regional universities includes:

-

3.5% growth in Commonwealth Grant Scheme funding to regional and remote campuses

-

A$5,000 payments for students from outer regional, remote and very remote areas who transfer to Certificate IV study or higher, for at least one year

-

a new A$500 million-a-year fund for programs that help Indigenous, regional and low socioeconomic status students get into university and graduate

-

A$48.4 million in research grants for regional universities to partner with industry and other universities to boost their research capacity

-

A$21 million to set up new regional university centres

-

guaranteed bachelor-level Commonwealth-supported places to support more Indigenous students from regional and remote areas to go to any public university.

The government has also promised a A$900 million industry linkage fund. The aim is to help universities build stronger relationships with STEM industries and provide work-integrated learning opportunities.

Read more: New modelling shows the importance of university research to business

What does this mean for regional universities?

The Regional Universities Network welcomed the package. Bartlett said:

Lowering the cost of the student contribution for courses such as nursing, allied health, teaching, agriculture, engineering, IT and maths should encourage greater uptake by regional students in these areas. It is estimated that there should be more places in the regions. More graduates from our universities will produce more graduates to work in regional Australia in areas of skills need.

As the COVID-19 economic battle is ever evolving, the tertiary education sector must be vigilant. Spending should be prioritised to make it equitable for all universities and their communities. Decision-makers need to be aware of the key issues affecting the success of tertiary education in the regions and their dependent communities.

Regional engagement activities and programs, backed by increased funding, improve the prospects of successfully weathering the COVID-19 storm. Regional universities can deliver national benefits, by overcoming skill shortages and meeting local workforce needs, while contributing to public and private community services such as schools and health services.

The government package is important for all universities, but this support is the only means of regional universities surviving. If they are not supported and are forced to close, regional education and economies will suffer for many years.

– ref. Why regional universities and communities need targeted help to ride out the coronavirus storm – https://theconversation.com/why-regional-universities-and-communities-need-targeted-help-to-ride-out-the-coronavirus-storm-143355