Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michael Plank, Professor in Mathematics, University of Canterbury

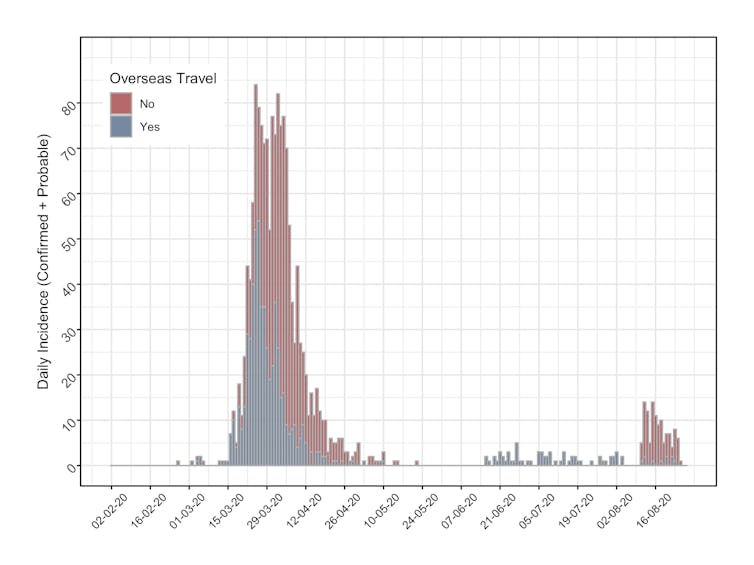

As Auckland prepares to relax restrictions on Monday, contact-tracing data show the rapid decision to place New Zealand’s largest city under alert level 3 lockdown has undoubtedly prevented an explosive outbreak of COVID-19.

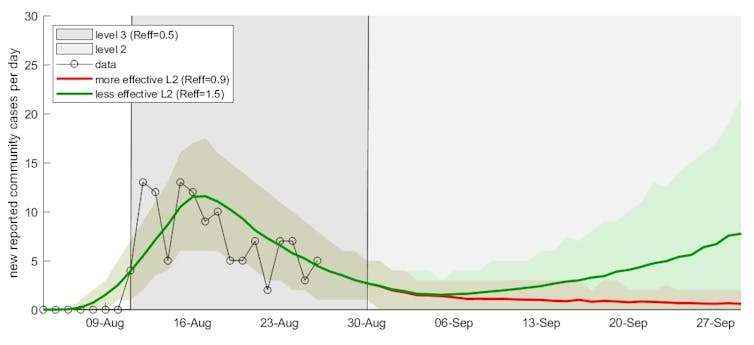

Our model of COVID-19 spread in New Zealand shows the extension by an extra four days at level 3 until Monday has also increased our chances of eliminating community transmission of the virus by about 10%.

Auckland has been at alert level 3 since August 12, less than 24 hours after the first new community cases of COVID-19 in more than 100 days were reported.

Contact-tracing data show that before Auckland’s move to level 3, the reproduction number was between 2 and 3. This means that on average each new case passed the virus on to two or three other people.

If we hadn’t acted quickly, we would have had hundreds of new cases by now, and it would have become far more difficult to bring the outbreak under control.

New Zealand’s largest cluster

The Auckland outbreak is New Zealand’s largest and most complex cluster to date, with 159 people, including 85 who have tested positive and their household contacts.

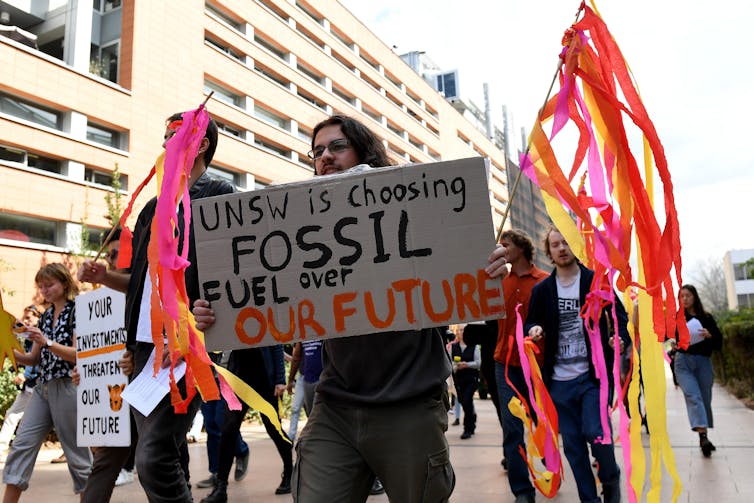

We have seen transmission in workplaces, churches, public transport and shops, as well as within households.

It has affected Auckland’s Pacific population, who are at higher risk of severe outcomes from the disease. The risks associated with this cluster are higher than those in the first outbreak, reinforcing the need to take a precautionary approach.

Read more: 6 months after New Zealand’s first COVID-19 case, it’s time for a more strategic approach

The contact tracing system has been a significant help in containing this outbreak, with more contacts traced faster than earlier in the year. But contacts between strangers are harder to trace, and some could slip through the net.

The fact that the infection was passed between strangers on bus journeys shows how stealthily this virus can spread. It also emphasises how rapidly it can move around the city.

Melbourne attempted to contain its COVID-19 outbreak by locking down certain postcodes, but the virus was always one step ahead and ultimately this tactic didn’t work. The Auckland-wide lockdown has proven to be the right approach.

Avoiding closed, crowded spaces

Although level 3 restrictions have been effective in preventing exponential growth of the cluster, active cases almost certainly remain in the community. These could easily spark a new outbreak if we relax too soon.

The extra time at level 3 will give us more confidence that the cluster is contained, but it is unlikely we will have completely eliminated the outbreak by Monday.

The Mt Roskill mini-cluster, which now has eight cases, shows we haven’t completely closed this outbreak down yet. But the fact this has now been genomically linked to the main Auckland cluster means it is unlikely to be part of a much bigger outbreak.

How we behave as we go into alert level 2 next week will be crucial in preventing a resurgence. If we can keep the reproduction number below 1, we will eventually eliminate the virus. But if the reproduction number goes above 1, there is a high chance the outbreak will flare up again.

Restrictions on gatherings of more than 10 people and compulsory mask use on public transport will help. But the best way to prevent a resurgence of the virus at level 2 is if we all avoid the three Cs: closed spaces, crowded places and close contacts.

Read more: Genome sequencing tells us the Auckland outbreak is a single cluster — except for one case

Likelihood of regional spread

So far the cluster has remained largely contained within Auckland. Restrictions on travel in and out of the city have certainly helped to stop the cluster from spreading to other regions.

From Monday, people will be able to travel to and from Auckland freely, and although we have reduced the number of cases in Auckland over the last two weeks, there is a risk of spreading COVID-19 around the country.

The virus could still pop up anywhere and it is essential all New Zealanders stick to level 2 rules, whether they live in Whangārei, Invercargill or anywhere in between.

We don’t necessarily have to get to zero new cases before lifting the level 3 restrictions. As we have seen before, case numbers bounce around from day to day. We may get zero or one cases one day, and four or five the next. What is more important is the type of cases we are seeing.

Last time we were at level 2, from May 14 to June 8, we had a handful of new cases but these were all acquired from a known source. If we get new cases with no apparent link to the cluster, or cases who have been in high-contact situations while potentially infectious, this will be a red flag. It would tell us that there could be many more cases we have missed.

But if most of our new cases are close contacts of existing cases, and ideally already in isolation, this is a good sign that the cluster has been successfully ringfenced.

What next

The criteria for moving to level 1 should be a high probability of elimination. Our previous modelling shows this requires a period of at least ten consecutive days with no new cases, along with widespread testing of anyone with COVID-19-like symptoms.

Once we reach this stage, we should review our level 1 settings. We need to find a way of enabling our economy and society to function while staying ready for the next outbreak. Regular testing of people staying and working in quarantine facilities is one part of this.

But as long as the global pandemic continues to rage, we can’t rely solely on our border — we all need to play our part. Mass masking, precautionary physical distancing and widespread testing at level 1 are low-cost interventions that give us a better chance of detecting an outbreak before it grows too big.

This will minimise the risk of another lockdown next time the virus appears in our community.

– ref. Auckland’s rapid lockdown has given New Zealand a better chance of eliminating coronavirus – again – https://theconversation.com/aucklands-rapid-lockdown-has-given-new-zealand-a-better-chance-of-eliminating-coronavirus-again-145011