Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Clare Littleton, Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the Centre for Healthy Sustainable Development, Torrens University Australia

The “social determinants of health” is a fancy way of describing a simple idea: that a person’s health is influenced not just by what they eat or do but also by social factors.

These include:

-

access to education (including in early childhood)

-

your parents’ income

-

being able to afford fresh fruit and vegetables

-

access to decent housing and healthcare

-

whether a child or their family face discrimination.

There’s growing awareness among researchers and policymakers that addressing the social determinants of health is crucial to tackling inequities in Australia.

And it’s during childhood these factors start greatly influencing a person’s life trajectory.

However, this growing awareness of how social factors affect children’s health is not always reflected in policy.

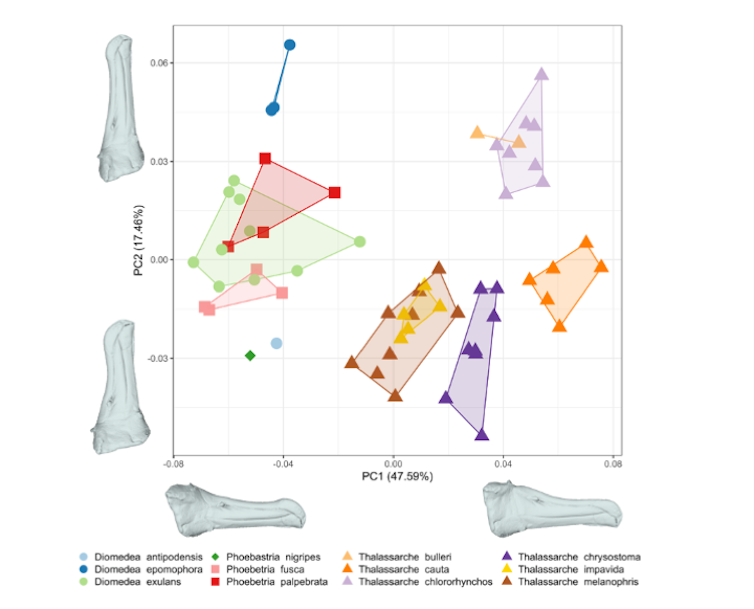

Our study, published in BMC Public Health, involved analysis of the strategies at the heart of 26 Australian health and education wellbeing policies. We found just 10% addressed the social determinants of health.

This is troubling. Failing to tackle the social determinants of health means reproducing disadvantage again and again.

Shutterstock

Read more:

The social determinants of justice: 8 factors that increase your risk of imprisonment

What we did and what we found

Our study involved analysis of 26 state and national strategic health and education wellbeing policies:

CC BY

We selected these policies by reviewing all publicly available federal and state/territory health department strategic policies, and selecting key education wellbeing policies dated from 2009 on.

We picked out policies with a title that addressed the issues of children, youth, paediatric, adolescent, youth health, or families, as well as education policies that included “wellbeing” in the title.

We also selected whole-of-government policies addressing child and youth health issues, and health promotion or disease-prevention policies with a chapter or extensive section dedicated to children.

What we found was disappointing. Just 10% of the 26 policies we analysed suggested action on the social determinants of health.

And while Australian governments broadly acknowledge the importance of addressing social factors contributing to health and that some groups of children are left behind, there was an imbalance towards an acute care approach.

In other words, we saw a focus on dealing with problems once children are sick rather than looking at what needs to be addressed to prevent problems emerging in the first place.

It is the most vulnerable children who present more often in emergency departments. Addressing this means taking action on the social factors we know will make things fairer for all children.

The good news

The good news is we saw Australian policymakers were paying attention to some of the social determinants of health. For example:

Early childhood and education: many policies included a focus on the first 1,000 days of a child’s life, and the different levels of education. This is good news because we know if children are engaged in childcare, kindies, and schools during childhood they will have better health outcomes throughout life. Several policies also suggested strategies for children who are disengaged with the education system.

Parental workplace conditions: across the policies we analysed, there was recognition parental employment conditions contribute to the health of children. However, more work needs to be done in this area. One area often missed is the need for affordable childcare.

Healthy regulatory settings: several policies suggest we need to address marketing directed at children in close proximity to schools, playgrounds and

childcare centres. This is positive but we still see junk food marketed to children across Australia, especially in sport. We see an opportunity for more regulation in this area.

Healthy spaces: we could see work is underway across a range of policies to make sure children and families have green space to play in, and that cities are more walkable and bike-friendly.

Housing: some policies, especially when talking about youth, are starting to understand housing is crucial to health and wellbeing. This is welcome, but there’s also an opportunity to expand this area, as housing grows more unaffordable for many.

Including children’s voices: we were excited to see acknowledgement across several policies that it’s important for children and youth voices to be heard in the policy design process. This reflects a commitment to Article 12 of the United Nations Rights on the Convention of the Child, specifically that “Children have

the right to have their views taken into account in matters that affect them”.

Mental health: we were also pleased to see a stronger connection between health and education departments when addressing mental health. This could be a key part of tackling the increasing levels of psychological distress some children and youth are experiencing.

Shutterstock

Where to from here?

Our study looked at just a snapshot of policies but represents a possible starting point for a broader discussion about how Australian policymakers could expand their focus on the social determinants of health.

We need a health system that balances both acute care and prevention. This could help toward the goal of ensuring all children living in Australia have better health outcomes and a fairer start in life.

Read more:

New asthma medicine restrictions will hurt the poorest children the most

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Who gets to be healthy? The ‘social determinants of health’ can reduce inequities, but many policies neglect them – https://theconversation.com/who-gets-to-be-healthy-the-social-determinants-of-health-can-reduce-inequities-but-many-policies-neglect-them-210961