Though the Oslo Accords and its signatories made many promises to the Palestinians, in reality, it carved Palestine up into bantustans and ghettos with limited self-autonomy for Palestinians on a minuscule portion of their homeland.

By Yumna Patel

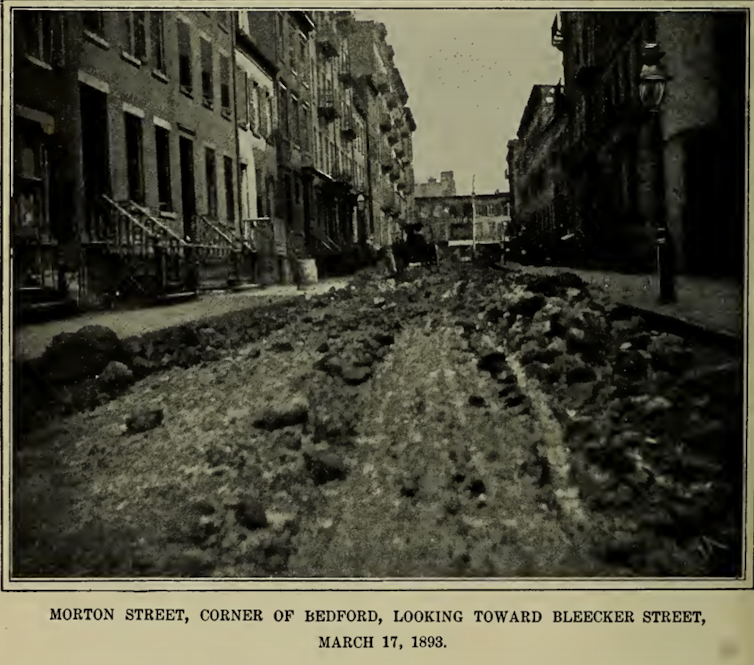

On September 13, 1993, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) Yasser Arafat shook hands in front of an elated US President Bill Clinton on the White House lawn.

The image capturing that handshake came to be one of the most famous images of all time, representing one of the most defining moments in recent Palestinian history.

It was the day that the Declaration of Principles (DOP), or the first Oslo Agreement (Oslo I) was signed, kicking off the so-called peace process that was meant to culminate with “peace” in the region and resolve the so-called “conflict”.

But the Oslo Accords never actually promised an independent Palestinian state, or even something that remotely resembled it. In reality, it carved the occupied Palestinian territory up into bantustans with limited self-autonomy for Palestinians on a minuscule portion of their homeland.

It paved the way for Israel to swallow up more land, resources, and tighten its grip on the borders and the people living within it.

Even the promises that were made — halts on settlement construction, withdrawal from certain areas of the occupied territory, and the eventual transfer of control of the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority (PA) — never happened.

Wednesday marked 30 years since the first Oslo Accords were signed. And though final status negotiations have failed repeatedly over the decades, the Oslo Accords have remained in effect, creating a unique situation on the ground for Palestinians.

The PA, which was set up as an interim government, has become permanent, and its leaders have remained unchanged for 17 years. Both the Fatah-dominated PA in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza have evolved into authoritarian regimes, causing many young Palestinians to declare their governments as “subcontractors of the Israeli occupation”.

In the meantime, Israel has a tighter grip than ever before on Palestinian life and land, with Gaza under tight blockade and the West Bank carved up into small cantons, or apartheid-style “bantustans,” as analysts put it.

With each passing year, the Israeli government has become increasingly right-wing, breaking its own records on violence against Palestinian communities and the construction of illegal settlements deep in the occupied West Bank and Jerusalem.

To say that the reality on the ground is desperate would be an understatement. And many Palestinian youth, who grew up in the shadow of the accords and all its false promises, blame the accords, or “Oslo” as it is locally called, in large part for the situation they find themselves in today.

Setting the stage

Before that fateful day on the White House lawn in 1993, there was a lot happening for Palestinians both at home and abroad.

From 1987-1993, the Palestinian streets were in upheaval. It had been two decades since Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, and Palestinians were fed up.

The First Intifada, or the first Palestinian uprising, took Israel and the world by surprise. A mass civil disobedience campaign swept the country, and turned into years of protests and subsequent repression by the Israelis.

Despite the violence that plagued the Palestinian streets, many Palestinians found themselves hopeful — that by standing up to the occupation, they could change their reality.

Then, in the fall of 1991, the world convened in Madrid for a “peace conference”. Sponsored by the US and the Soviet Union, it was the first time Israel and the Palestinians were to engage in direct negotiations.

The PLO, which is internationally recognised as the representative of the Palestinian people, was operating in exile in Tunisia, and was barred from attending the conference. In its place, a joint Jordanian-Palestinian delegation was tasked with representing the Palestinian people instead.

Dr Hanan Ashrawi was one of the advisors to the delegation.

“We went with a sense of mission that we are representing a people who have dignity, who have rights, who have courage, who have defied this military occupation. And we are going to present ourselves to the world, and we are going to extract our rights,” Ashrawi told Mondoweiss, reflecting on the moment in history that propelled her onto the global stage.

“So we were confident, and there was a spirit of optimism, maybe naivete, if you will,” she said.

The Madrid conference set the stage for years of peace negotiations facilitated by Washington and Moscow. Despite its flaws, those involved in the Madrid conference, like Ashrawi, seemed hopeful that political negotiations could really lead somewhere.

“That was a period, albeit a short-lived period, of hope, of optimism, of confidence,” Ashrawi said.

“And when we came back, people believed that they could achieve liberation through a political process, but that these were dashed afterwards completely.”

Backchannel negotiations

While public negotiations were being held on the global stage in the months after the Madrid conference, a different set of negotiations were being held behind closed doors between two unlikely partners.

In 1993, in Oslo, Norway, Israel and the PLO engaged in backchannel discussions that resulted in an unprecedented conciliation.

The PLO, a militant liberation organisation, recognised the state of Israel and its “right to exist in peace and security”. In exchange, Israel recognised the PLO as a “representative of the Palestinian people,” falling short of actually recognising the Palestinians’ right to sovereignty.

After months of secret negotiations, and in a shock to many Palestinians, Rabin and Arafat shook hands in September 1993, as the Declaration of Principles (DOP), or first Oslo Accords (Oslo I), were signed.

The move came as a shock to many Palestinians, including those who had been engaging in public peace negotiations for years, and were seemingly unaware of the secret deal that was materialising behind the scenes.

“The signing of the DOP was a real disappointment,” Dr Ashrawi told Mondoweiss. “I wasn’t upset or disturbed because there were backchannel discussions that we weren’t part of, or that it was signed behind our back.

“I said then very openly, that I don’t care who signs it or who negotiate it. I care about what’s in it, what’s in the agreement.”

When Dr Ashrawi saw the agreement, she said she was “extremely disappointed” and concerned over what she described as “built-in flaws,” which she said she felt at the time would end up backfiring on the Palestinians.

“Because [the accords] did not challenge the reality of the occupation, and they did not deal with the real issues, with the core issues, with the causes of the conflict itself. The totality of the Palestinian experience was excluded. The fragmentation was maintained, the phased approach was maintained, the Israeli actual control on the ground was maintained, and all the postponed issues had no guarantees, no oversight.”

Dr Yara Hawari, a political analyst for Palestinian think tank Al-Shabaka, said the Oslo Accords “were always set up to fail”.

“[They were set up] to make Palestinians lose out on what was supposedly peace negotiations, and so many decades on we’ve seen that actually, it has been complete capitulation for the Palestinian people.”

What did the accords say?

The Oslo Accords were a number of agreements, signed between 1993 and 1995, that laid the foundation for the Oslo process — a so-called peace process that, over the course of five years, was to culminate in a peace treaty that would end the Israeli-Palestinian “conflict”.

So, what exactly did the accords say? And why were they so controversial?

“The Palestinians were told that the Oslo Accords would be a peace process, and that over an interim period, Palestinians would be led to eventual statehood. And it was designed to be a phased process.

“So at each stage, Palestinians would be granted more and more sovereignty,” Dr Hawari said.

“But in reality, what we saw was that the West Bank was completely divided up into bantustans. The Gaza Strip and the West Bank were completely separated from each other, and the Palestinian leadership was turned into this service-functioning body, and Palestinians were deprived of complete autonomy.”

While they outlined economic and security agreements, the creation of the interim Palestinian National Authority (PNA), and limited Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza, the accords never actually agreed upon any of the major issues plaguing the Palestinian struggle: the borders of a future state, illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank, the return of the Palestinian refugees to their homes, and the status of Jerusalem as a future capital.

“The totality of the Palestinian experience was excluded. The fragmentation was maintained, the phased approach was maintained, the Israeli actual control of the ground was maintained, and all the postponed issues had no guarantees, no oversight, no arbitration, and no accountability,” Dr Ashrawi said.

There was never any intention to accept any kind of sovereignty or self-determination for the Palestinians.

The fallout

In the years after the first Declaration of Principles was signed, the new Palestinian Authority went into full swing, forming their new interim government and welcoming back home hundreds of Palestinians who had been living in exile.

But by 1999, when the 5-year-interim period laid out by the accords had ended, little had been accomplished in terms of final status negotiations.

Israel had not followed through on its promise to fully withdraw from certain areas of the West Bank and Gaza, and despite promises to halt settlement construction, Israel was still building Jewish-only settlements on Palestinian land.

And in 2000, spurred on by Ariel Sharon’s inflammatory visit to the Al-Aqsa mosque, the Second Intifada erupted. Israel’s military forces reoccupied the West Bank, and the next few years were marred by mass killings, arrests, and the construction of an illegal wall that separated families and annexed more Palestinian land.

Whatever fragments had remained of a peace process vanished.

The settlements and shrinking spaces

In the midst of the Second Intifada, America’s attempts to revive a peace process with the Camp David summit in 2000 proved to be futile. And yet, though the peace process was dead in the water, the framework laid out by the Oslo Accords remained in place.

That meant Palestinians were left with a government that was intended to be temporary but with no independent state for that body to govern. And Israel, through military force, still had control over the borders, resources, and effectively, the lives of millions of Palestinians

“The key promise of Oslo was Palestinian statehood, and we know that has obviously not been achieved,” Dr Hawari told Mondoweiss.

“Instead, what we see is these little pockets of false Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank. There were many other promises that were made as well: economic promises, promises to do with control over resources, and actually, none of those have been fulfilled.

“The only people that have won from the accords, or who have actually gained, are the Israeli regime, which now controls the West Bank in its entirety, has Gaza under siege, and basically has looted all of the Palestinian resources.

“And this was laid out in the Oslo Accords.”

In the years following the signing of the Oslo Accords, Palestinians witnessed their spaces shrinking rapidly, as Israel promoted vast settlement construction deep within the occupied West Bank and Jerusalem.

Between the signing of the Oslo Accords and the outbreak of the First Intifada, the number of Israeli settlers in the West Bank increased by almost 100 percent.

In the year 2000, the settler population in the West Bank stood at just over 190,000. Today, that number has surpassed 500,000 settlers, all of whom are living on Palestinian land, in violation of international law.

Including settlers living illegally in East Jerusalem, the settler population in the occupied Palestinian territory has surpassed 700,000.

An increase in settler population, coupled with an extreme right-wing Israeli government, has meant a significant increase in settler violence, with Palestinian civilians on the frontlines.

In the first eight months of 2023, the UN documented more than 700 settler attacks against Palestinians. The attacks have resulted in damage to homes, property, farmland, physical injuries, and even death.

Because of the maps drawn by the Oslo Accords, the PA only has security jurisdiction over 18 percent of the West Bank, meaning that in the event of a settler attack, most Palestinian civilians are left to fend for themselves.

A disillusioned youth

In the wake of the Oslo Accords, a new generation of Palestinians was born that would come to be known as the “Oslo Generation” — whose youth would be defined by false promises and loss of life, land, and the power to choose their own future.

“We witness our own family and friends being killed and arrested on a daily basis. We get humiliated at military checkpoints whenever we’re trying to leave or enter our cities or villages.

“And we witness our people being expelled from their land while more and more settlements are being built in their place,” Zaid Amali, a Palestinian activist in Ramallah, told Mondoweiss.

When asked what he thought of Palestinian and international leaders still promoting a two-state solution and “peace negotiations” on the global stage, Amali responded:

“It may be more convenient for them to stick to that framework, but it’s very unrealistic and naive to still hang on to it because Israel has systematically destroyed the two-state solution.

“And to us as well, it feels insulting and disrespectful to keep talking about this in theory, when in reality, on the ground, it’s the complete opposite of what’s happening.”

In the 30 years since the first accords were signed, the Palestinian Authority, which was intended to be an interim government, has become permanent. And yet, elections have only ever been held twice in 3 decades. Any attempts over the last 16 years at holding elections or reviving reconciliation talks between rival factions have been squandered.

PA leaders in the West Bank and Hamas authorities in Gaza have consolidated power in the hands of a few elites while growing increasingly authoritarian, cracking down on dissent, censoring the media, and jailing and even killing dissidents.

“The way the system became, in a sense, right now is quite disappointing,” Dr Ashrawi told Mondoweiss. Without naming names, Ashrawi continued, “People became more concerned with power, with control, other than with service.

“[They became] more concerned with self-interest, influence, and the trimmings of power rather than the whole idea of contributing and serving the people.”

When asked how things deteriorated into the present-day situation, Dr Ashrawi attributed it to an overall “abuse of power.”

“There were gradually constricting spaces for freedoms and rights that ultimately, now you don’t even have a legislative power. Even the judiciary was subjugated to the executive.

“The executive became concentrated in the hands of the few, and so we have distorted any semblance of democracy that we may have had and that we have tried to establish even under occupation,” she said.

“I don’t blame the occupation for everything. There are things under our control that were abused and distorted.”

The concentration of power in the hands of authoritarian figures like President Mahmoud Abbas has meant that an entire generation, like Zaid Amali, is now nearing or surpassing the age of 30 without ever having participated in a national election.

Amali, 25 years old, said it’s an extremely frustrating reality for young Palestinians like him.

“It’s frustrating because we should be able to elect our own government in a democratic way,” he said.

“This government should reflect our interests and manage the needs of the Palestinian people and represent us in a true way.”

“But on the contrary, it’s actually serving the interest of the few at the expense of the majority in Palestine. And when we talk about Palestinian youth, they do form the majority of the Palestinian population.

“So, for us young Palestinians, it is, again, very frustrating to see that this government is not really working in our interest. But oftentimes, unfortunately, [it is] against us.”

Turning to armed resistance

In 2023, the Palestinians who were born the year the Oslo Accords were signed turned 30. Until today, none have had the opportunity to participate in political life on a national level. Economically, their opportunities are few and far between.

Unemployment in occupied Palestine is close to 25 percent — while in Gaza alone, that number is closer to 50 percent.

All the while, Israel’s grip on Palestinian life grows ever tighter. 2022 and 2023 marked record-breaking years for Israeli violence against Palestinians, as well as settlement expansion. The situation on the ground has grown desperate, causing many young Palestinians to take matters into their own hands.

Since 2022, the West Bank has seen a resurgence in armed resistance, with militias led by Palestinians as young as 18 years old. Many of the armed resistance groups, some of which operate under a banner of unity and defiance of factional rivalries, have seen massive popular support.

But both the Israeli and Palestinian governments have deemed these armed militias as a threat to the status quo cemented after the Oslo Accords. As part of its policy of security coordination with the Israelis, which was outlined in the accords, the PA has in recent months jailed dozens of Palestinian fighters, along with political dissidents, activists, journalists, and university students.

While some fighters have accepted clemency and handed over their weapons willingly, those who haven’t are being hunted down and arrested.

“We don’t know who’s against us, the [Palestinian] Authority or the Israeli army,” one young man in the Jenin refugee camp told Mondoweiss, just days after a visit by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to the camp — his first visit in 11 years.

“For four years before my arrest [by the Israelis], I was also wanted by the PA. We don’t feel safe at all with the presence of [the PA].”

“Right now, they are actually working against us,” the young man said, referring to the PA’s arrest campaign targeting fighters in areas like Jenin, as part of an ongoing joint security cooperation effort between the PA and the Israeli government.

“It’s all one operation, one operation with the Israeli military and intelligence. When the army comes to attack us, the PA goes and hides away in their stations.

“They [the PA] are trying to get us to turn ourselves in and hand over our weapons, and give up this cause that we are fighting for. But we won’t give it up, no matter what.”

But the PA’s attempts to curb resistance only seem to be backfiring. Public opinion polls from this year show that 68 percent of Palestinians support armed resistance groups, and close to 90 percent believe the PA has no right to arrest them.

Additionally, more than half of Palestinians believe that the continued existence of the PA serves Israel’s interests, not the interest of the Palestinian people.

“This is a leadership that has led us to a situation where we live in bantustans and essentially in ghettos in the West Bank, Gaza, and colonised Palestine,” Dr Hawari said.

“So we have to reckon with that, and that is internal work that Palestinians have to focus on.

“For us to have a brighter future, we have to take a very good look at our leadership and reassess what we want that leadership to look like.

“Do we want it to be a leadership that capitulates and collaborates with our oppressors? Or do we want a leadership that is revolutionary and centers our freedom in their narrative?”

Republished under a Creative Commons licence.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

![]()