Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Martien Lubberink, Associate Professor of Economics, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

Getty Images

With the transfer this week of Kiwibank’s assets to a state-owned company, the New Zealand crown has now taken full control of the bank. At an estimated cost of NZ$2.1 billion, the change of ownership has all the hallmarks of a government bailout.

Former owners NZ Post, the Accident Compensation Corporation and the New Zealand Superannuation Fund could be considered justified in wanting to get out. It was an ailing bank in the making.

The main capital ratio dropped from a healthy 13% in 2018 to 10.5% this June – the minimum level the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority requires banks to meet in order to be seen as unquestionably strong.

Return on equity lingered at around 6% per year, while the bank’s larger competitors offered a return twice as high. Added to this were the high capital requirements announced by the Reserve Bank in 2019 and which are now being phased in.

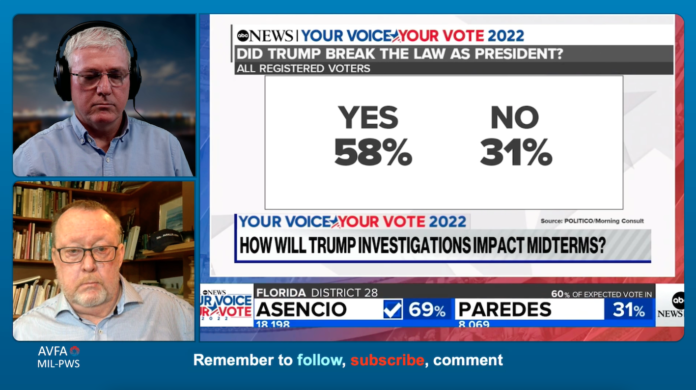

Fiona Goodall/Getty Images

Too important to fail?

The government has promised to recapitalise the bank to help it grow. Whatever the bailout is called officially, it was the only realistic option. That said, the government cited several reasons for its decision to transfer control.

Read more:

Hostage to fortune: why Westpac could struggle to find the right buyer for its NZ subsidiary

One was to keep the bank in New Zealand hands. The government has also pledged its full commitment to support Kiwibank to be a genuine competitor in the banking industry. And lastly, the transfer allows “all future profits to stay in the country – unlike the Australian-owned banks.”

But these justifications should not be taken at face value, and it is worth looking at them one by one.

Keeping profits in the country

The idea that keeping profits in the country automatically creates value for New Zealanders is by no means a given.

Kiwibank’s latest reported profits were $136 million, or $25 per New Zealander. This pales in comparison to the profits reported by the big four Australian-owned banks: in total, about $6 billion, or $1,200 per head of population.

Other banks either keep their profits or they pay them out to their owners and shareholders. In practice, these are institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies – some of them New Zealand-based.

Moreover, New Zealanders who own shares in Australian banks will receive dividends. Unlike the owner of Kiwibank, these Kiwi investors will benefit directly from their investments.

Lastly, it should be noted that banks have accumulated profits in New Zealand because of the increasing capital requirements. Since 2018, the four Australian-owned banks in New Zealand retained profits worth $12 billion. These would otherwise be transferred to their parents across the Tasman.

Again, these banks contribute to a stable financial system, keep profits in the country and do not need support.

Local ownership

In practice, all New Zealand banks are locally incorporated because of Reserve Bank requirements. Foreign-owned banks operate largely independently from their parents. This has led to inconveniences.

For example, ASB bank cannot freely use new technologies developed by its owner Commonwealth Bank, even though there would be efficiencies of scale if they were allowed to do so.

Also, creditors cannot hold a foreign parent bank liable when its New Zealand subsidiary fails. It’s therefore unlikely that foreign ownership would significantly change Kiwibank’s operations.

But the prospect of foreign ownership could add value. It could encourage its management to step up efforts to grow and compete.

Viability and competition

With a 5% market share, Kiwibank is small and lacks the critical mass required to thrive and compete effectively. Its small size is already problematic, as the bank cannot serve large clients. The government, for example, does not rely on Kiwibank for its banking.

The growth opportunities for Kiwibank are further limited because the New Zealand banking market is tightly regulated and conservative. European banks, for example, are much further ahead when it comes to the adoption of new technologies. Money transfers between European bank accounts are executed in real time, while such transfers still take hours in New Zealand.

Read more:

Crypto platforms say they’re exchanges, but they’re more like banks

The government claims that the banking market has become more competitive since the establishment of Kiwibank. According to Finance Minister Grant Robertson, Kiwibank continues to put pressure on the big four.

That may be so, but other small competitors would do that too. Rabobank, for example, is competitive in farm lending. Other small banks remain well-capitalised and don’t face the same challenges as Kiwibank.

The risks ahead

The most likely way forward for Kiwibank is to further increase lending to riskier clients. Robertson has already alluded to this, arguing Kiwibank could be a disruptor in the industry by focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises.

The problem is that Kiwibank needs the expertise to do this. Adding capital is not enough. And the government will want to avoid Kiwibank taking on too much risk because that will put the future of the bank itself at risk.

On top of this is the risk of Kiwibank’s owner wanting to meddle with its operations. While the present government promises to respect operational independence, who knows what a future government might do.

Finally, there is the question of moral hazard – setting a precedent for other banks. What if one of the other, smaller banks finds itself in trouble? Will the government step in? Again, the decision to save Kiwibank suggests the future could be uncertain indeed.

![]()

Martien Lubberink does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The government taking full ownership of Kiwibank is a bailout in all but name – what are the risks now? – https://theconversation.com/the-government-taking-full-ownership-of-kiwibank-is-a-bailout-in-all-but-name-what-are-the-risks-now-189378