Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By David Smith, Associate Professor in American Politics and Foreign Policy, US Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Butch Dill/AP/AAP

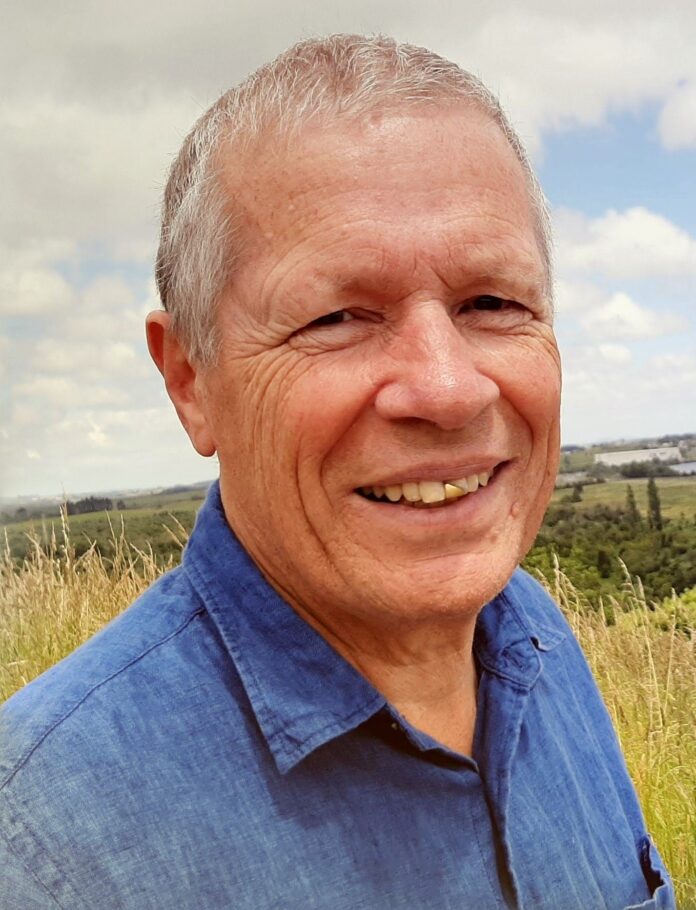

Ron DeSantis’s re-election as governor of Florida was one of the few bright spots for Republicans in an otherwise disappointing 2022 midterm election. DeSantis originally won the governorship by less than half a percentage point in 2018. in 2022, he defeated his Democratic opponent (and former Republican governor) Charlie Crist by more than 19% of the vote.

For the first time in years, Donald Trump may have a serious challenger to his domination of the Republican Party. Donors, media figures and other conservative elites are flocking to DeSantis.

The contrasts with Trump are obvious. DeSantis won re-election while Trump lost, and many Republicans hold Trump responsible for their losses this year. DeSantis’s allies also point to his policy victories, something largely missing from Trump’s presidency.

But winning a Republican primary requires winning over large numbers of evangelical Christians, and for them the calculus of victory is more complex than “check out the scoreboard”. Trump has always promised them a victory much bigger than legislative triumphs or even election wins. While DeSantis represents the orthodox conservative Christian uses of political power, Trump appeals to those who believe that only an apocalypse can save America.

The Kingdom of God

One of the most important Christian narratives is triumph over death, embodied in the resurrection of Jesus Christ and promised one day to all God’s people. Death is not just beaten, but humiliated. In the New Testament book of 1 Corinthians, the Apostle Paul taunts “O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?”

There will be other reversals of earthly fortune, because God’s grace does not follow established social convention. In the parable of the vineyard workers, Jesus tells his followers that in the Kingdom of God “the last shall be first, and the first last”.

Read more:

After Trump, what is the future of the Republican Party?

This passage has historically inspired enslaved and oppressed peoples to find a message of liberation in the gospels. But it has also encouraged relatively well-off people to imagine themselves as the persecuted “last” who will one day be first by God’s grace.

For orthodox Christians (referring not to Eastern Orthodox churches, but all adherents to core Christian creeds), politicians are not supposed to promise the Kingdom of God. The state and the Kingdom of God are separate realms, as Jesus himself explains. Nonetheless, political power has had important uses for Christians ever since Emperor Constantine made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire.

The Kingdom of DeSantis

Ron DeSantis exemplifies the orthodox American use of political power for conservative Christian ends. While he uses the updated language of fighting “wokeness”, DeSantis has used the governor’s office to pursue a time-honoured culture war agenda in Florida, reasserting the primacy of traditional family structures and gender roles and keeping children away from material that may conflict with their parents’ beliefs. DeSantis’s message of victory on election night was “Florida is where woke goes to die”.

DeSantis learnt from Trump that evangelical Christians don’t care much about the personal piety of their candidates. They want fighters, not Sunday school teachers. He taps into the idea that secular authorities are persecuting Christians in America, an old claim that has also been a centrepiece of Trump’s appeal to evangelicals.

But there are limits to how much DeSantis can emulate Trump. While DeSantis sounds like a politician with a law degree, Trump sounds like a tent revival prophet. Rather than rearguard culture war actions, Trump promises the redemption of America.

The Kingdom of Trump

In his first presidential run, Trump was notable for his scathing “American carnage” speeches about the fallen state of the nation. It was rare to hear an American politician talk his country down like that, but it appealed to Christians who thought that even their own leaders didn’t understand how bad things were.

His speeches this year are even darker. While DeSantis complains about “woke corporations”, Trump talks about “cesspools of blood”.

Trump’s vows to restore America’s glory and punish its enemies without mercy resonate with evangelicals, who long for a day of reckoning when everyone will be held to account. As president, Trump always hinted that bigger things were around the corner. In the words of Kimberley Guilfoyle at the Republican National Convention, “the best is yet to come!”.

In contrast, Trump warned that if Joe Biden won the 2020 election, “there will be no God” in America.

Even Trump’s “stolen election” claims fit a death and resurrection narrative. Remembering his remarkable 2016 victory in defiance of the polls, Trump’s most ardent supporters expect him to ultimately triumph, one way or another, despite the appearance of defeat in 2020.

Orthodox Christian politicians do promise such things, but Trump is not an orthodox Christian.

Trump’s original pool of evangelical Christian supporters included many Pentecostal and Charismatic Christians. Pentecostals and Charismatics are huge in number, but have often been marginalised by more powerful evangelical groups because of their physicality and their beliefs in personal prophecy and spiritual warfare. Some evangelical leaders have denounced Trump’s “spiritual adviser” Paula White as a heretic.

For many Pentecostals and Charismatics, Trump was such a radical break from political norms that he represented the fulfilment of biblical prophecy. They likened him to biblical figures like Cyrus the Great, a pagan king who was nevertheless chosen to save God’s people.

A subset of evangelicals known as Premillennial Dispensationalists saw Trump’s decision to move the American embassy in Israel to Jerusalem as a necessary step for bringing about Christ’s rule on Earth and the final confrontation with Satan.

This apocalyptic style does not appeal to all conservative evangelicals, but in 2016 more orthodox-minded Christians couldn’t unite around a single candidate in opposition to Trump. Now, after six years of Trump influencing evangelical subculture and bringing previously marginal views to the centre of it, any challenger to Trump seeking evangelical votes faces a daunting task.

Lynne Sladky/AP/AAP

How abortion could make or destroy the 2024 Republican candidate

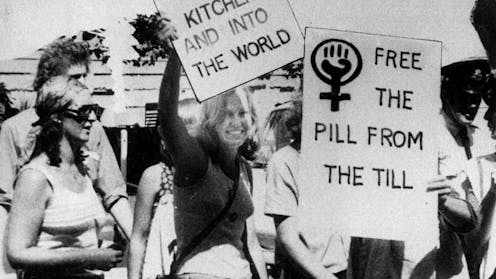

The most complicated issue in any contest between Trump and DeSantis could be abortion.

In 2016, Trump promised to appoint Supreme Court justices who would overturn Roe v Wade, the framework that had kept abortion legal in all states for nearly five decades. The Dobbs decision in 2022 overturning Roe was a direct consequence of Trump’s three appointments.

Read more:

The end of Roe v. Wade would likely embolden global anti-abortion activists and politicians

Trump’s supporters can point to the fulfilment of this longstanding conservative dream as far more significant than anything DeSantis has achieved, and Trump quickly claimed credit for it. But he reportedly also worried that Republican legislators were going too far for voters with abortion bans, and that the issue could hurt him politically in 2024.

He was right to worry. The abortion issue is widely recognised as one of the main reasons Republicans did so poorly in the midterm elections.

Before the Dobbs decision, DeSantis signed a law prohibiting abortion after 15 weeks in Florida, with no exemptions for cases of rape or incest. The law survived a legal challenge and DeSantis suspended a state attorney who refused the enforce the law.

After Dobbs, which allows for even more extensive abortion bans, DeSantis said Florida would “expand pro-life protections” but has so far declined to say what these would be. Some Florida Republicans may push for tougher restrictions after making big gains in the state legislature at the midterms.

Both Trump and DeSantis would have difficult decisions to make about whether to try to outflank each other on the abortion issue, or to distance themselves from Republican extremism. Abortion bans are increasingly unpopular even in the Republican Party, but these are among the most prized goals of religious activists who vote in Republican primaries.

Primary contests are highly unpredictable, and there is little current polling on how evangelical Christians compare the two most likely candidates. Trump secured 81% of the white evangelical vote in the 2020 election, but a contest with DeSantis could open deep divides among evangelical conservatives – at least until the winner faces a Democrat.

![]()

David Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Evangelical Christians are crucial voters in Republican primaries. Would they support DeSantis or Trump? – https://theconversation.com/evangelical-christians-are-crucial-voters-in-republican-primaries-would-they-support-desantis-or-trump-194914