Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Andrea Jean Baker, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, Monash University

Santiago Felipe/Perth Festival

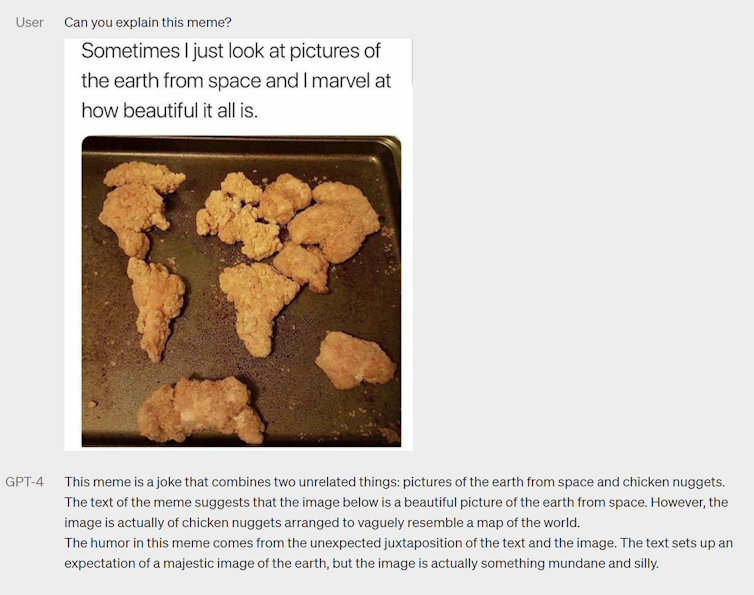

Kathleen Hanna yells like she did in the 1990s, pushing the toxic male patriarchy out of the moshpit at Melbourne’s The Forum on the eve of International Women’s Day.

Hanna’s band Bikini Kill rampages through hits such as Suck My Left One, thrilling a happy, bopping crowd of parents with their teenaged children laced with a mixed gender of preppie and diehard punks, goths and curious spectators.

Across town at the Northcote Theatre the next day, Peaches comes out with a walking frame, wearing breast-shaped slippers with bright red erect nipples.

The popular sexual exhibitionist is still hoarsely rapping about abortion, and now the debate over the end of Roe vs Wade, with songs like Boys Wanna Be Her. She later wades into the beloved audience inside a large inflatable penis.

In Perth, a few days later, Björk’s echo-filled, childlike voice is as harrowing and powerful as ever.

These artists, all now aged in their 50s, are popular provocateurs, pulsating with rage. Feminism, ageism, sexism, transphobia, racism, capitalism and environmentalism are their musical agenda.

Do-it-yourself ethos

As Gen X, third-wave feminist icons, Peaches (Merrill Nisker), Bikini Kill and Björk grew up during the punk movements of the 1970s and ‘80s.

Based in Olympia in Washington State, Bikini Kill was part of the Riot Grrrl movement in the early 1990s, funnelling the do-it-yourself punk ethos into zines, songs like Rebel Girl, and confrontational live shows.

Bikini Kill encouraged women and girls to start bands as a form of “cultural resistance”, challenging masculine toxicity long before #MeToo.

During the 1990s in Canada, Nisker formed a Riot Grrrl band, Fancypants Hoodlum.

By 2000, aged 33 and recovering from cancer and a heartbreak, she renamed herself Peaches. Her solo electro-pop album The Teaches of Peaches became a feminist classic, with singles like Lovertits.

Mona/Jesse Hunniford. Image courtesy of the artist and Mona Foma

Recording music since the age of 11 in Iceland, in 1992 Björk left The Sugarcubes, the alternative rock band she co-formed in 1986.

Björk’s first solo album came out in 1993, with huge hits like Human Behaviour about the way humans act and interact.

Thirty years on, they are all still making music.

Read more:

Harder, faster, louder: challenging sexism in the music industry

Women supporting each other

Bikini Kill are killing it during their all-ages gigs at The Forum.

The Forum’s iconic roman statues look down from the ceiling. Lead singer Hanna wears a khaki green, girly dress with pink punky tights, backed up by Kathi Wilcox on bass and Sara Landeau (from The Julie Ruin) on guitar. Drummer Vail is sick tonight, so Lauren Hammel from Victoria’s Tropical Fuck Storm is filling in.

Photo Credit: Mona/Jesse Hunniford. Image courtesy of the artist and Mona Foma

Hanna tells us she has “a gratitude journal” now, but remains Riot Grrrl-fuelled about the Trump era, rape, abortion, trans rights and Black Lives Matter.

She tells how during the 1990s audiences once spat in her face and threw things at the band on stage. These days they rarely do.

Hanna’s demeanour softens when a young female audience member gives her a carboard sign reading “Kathleen please draw my next next tattoo based on [the song] Feels Blind”.

At Peaches’ performance, the eclectic crowd is enthusiastically cheering her on.

Photo Credit: Mona/Jesse Hunniford Image courtesy of the artist and Mona Foma

Leaning towards us, Peaches asks what The Teaches of Peaches meant to everyone when it was released, “and what does it mean collectively together now?” The crowd cheers louder as if their favourite footy team has won the grand final.

Her encore Fuck the Pain Away, with Melbourne feminist punk singer Amy Taylor, has the floorboards of the colonial theatre thumping.

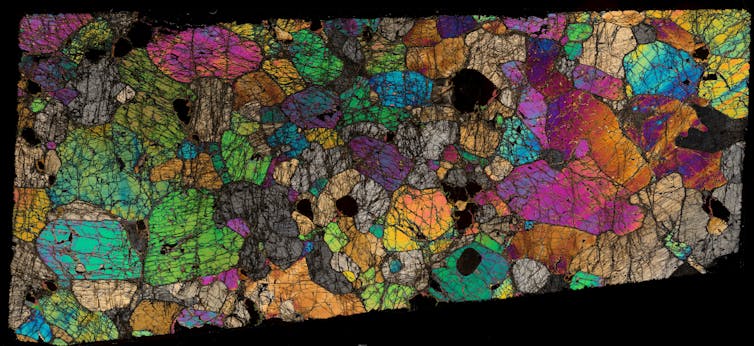

For Perth Festival, Björk is performing her sci-fi pop extravaganza Cornucopia in a purpose-built 5,000-seat stadium.

Presented only a few times globally, Cornucopia is Björk’s most elaborate performance to date. Based on her 2017 album Utopia, she has described the show as “about females supporting each other”, our connection to Earth, and a plea to act on climate change.

In Perth, we have IMAX-sized visuals and a 54-channel surround system to garner an immersive multimedia experience in an Eden of bird sounds.

Argentinian filmmaker Lucrecia Martel directs the futuristic screens of lush green plants, live organisms, expanding fungus and blooming blood red and pink-tinged flowers.

An 18-person Australian choir, Voyces, opens and closes the concerts. Björk is also joined on stage by harpist Katie Buckley and the multi-talented Manu Delago on the Aluphone percussion instrument, keyboards, other electronics and water drums.

For Body Memory, the seven female flautists of Viibra are dressed in fairy costumes, circling Björk. A hula-hoop-like circular flute descends over Björk and down to the flautists, requiring four of them to play it.

Santiago Felipe/Perth Festival

The sound is spellbinding.

Two songs, Ovule and Atopos from her new album Fossora have their live global premiere at the concerts. They pay tribute to her mother, the Icelandic environmental activist Hildur Rúna Hauksdóttir, who died in 2018.

Towards the end of the concert, a video of 20-year-old Swedish climate change activist Greta Thunberg looms before us:

We need to keep fossil fuels in the ground and we need to focus on equity. If the solutions in the system are so impossible to find, then maybe we should change the system itself.

Much as Hanna and Wilcox from Bikini Kill said during their All About Women talks at the Sydney Opera House, Björk is optimistic in the young people advocating for change.

Read more:

Björk, digital feminist diva, helps cure our wounds in a visceral Sydney show

Changing the script

When I heard Bikini Kill, Peaches and Bjork were performing almost in the same week, I grabbed tickets immediately. I scored a trifecta of my favourite female artists.

It had been many years since I saw them perform live. Seeing them this time was an empowering reminder that women in their 50s are still out there, oozing with vibrant creativity, worthiness and relevance.

We are about the same age: creative, rebellious youths who grew under the shadow of the boy’s club in the punk movement.

Their performances continue to challenge a male-dominated industry defined by fleeting talent, youthful beauty and voyeurism.

Their voices are stronger than ever. Their musicianship is tight, and the onstage antics are imaginative, playful, colourful and fun. Their messages are uplifting and clear, intelligent and thought provoking, now tinged with a softened version of empathetic rage about social injustice.

I have been seeing music gigs for more than 35 years, but these performances left me breathless.

Read more:

At Mona Foma, I encountered death rituals, underwater soundscapes, worship – and transcendence

![]()

Andrea Jean Baker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Sexual exhibitionism, Riot Grrrl and climate change activism: 30 years of raging by Peaches, Bikini Kill and Björk, still going strong – https://theconversation.com/sexual-exhibitionism-riot-grrrl-and-climate-change-activism-30-years-of-raging-by-peaches-bikini-kill-and-bjork-still-going-strong-201388