Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

One potentially solid proposal came out of Scott Morrison’s extraordinary news conference, held on Tuesday morning against the backdrop of the fresh revelations about appalling behaviour in Parliament House.

Morrison said he was open to a conversation about having Liberal Party parliamentary quotas, and had been “for some time”, as his colleagues knew.

“I have had some frustrations about trying to get women preselected and running for the Liberal Party to come into this place,” he said.

“I have had those frustrations for many years going back to the times when I was a state director where I actively sought to recruit female candidates, whether it was for state or federal parliament.”

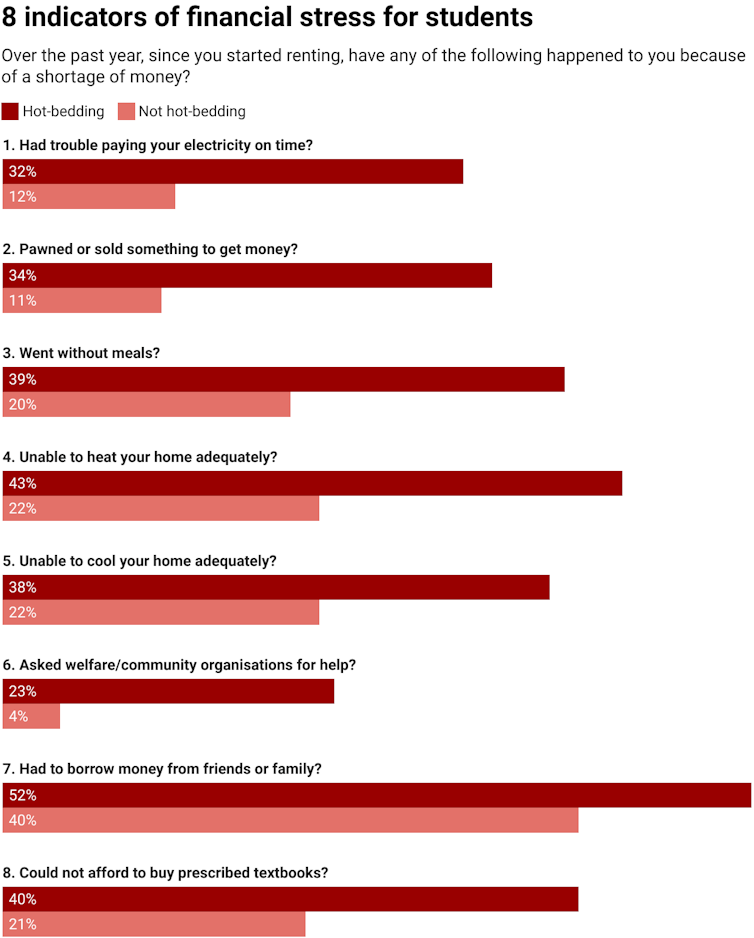

At present women form just over a quarter of the federal parliamentary Liberal Party (including both houses); in Labor, they are a little under half of caucus.

If Morrison is serious about quotas, he should immediately take action to have the Liberal Party, and its state divisions, advance the proposal.

It will also be up to women in the party who support quotas to seize the moment, while the PM is desperately searching for initiatives.

But even if this important debate takes off, it won’t be an easy one within the party, which has stood firmly against quotas, vociferously rejecting Labor’s embrace of them.

One well-placed source says there’s a growing minority in the party for quotas but there would still be a larger proportion against, including opposition from some of the female MPs.

Quotas also go against the democratisation push in the party. And they would take a long time to make a substantial difference to the ratio of men and women.

Tuesday’s news conference put on display the different faces of Morrison.

In part, his performance was a mea culpa and explanation for what critics attacked as his mishandling of the debate over the past weeks, notably when he recounted his wife’s advice, and he contrasted Australia’s peaceful women’s protest with the shooting of demonstrators in Myanmar.

In part and more broadly, he was trying to relate to women, to say he had heard their messages, understood their pain.

“I acknowledge that many have not liked or appreciated some of my own personal responses to this over the course of the last month, and I accept that,” he said.

“People mightn’t like the fact that I discuss these [traumatic events] with my family. They are the closest people in my world to me. That is how I deal with things, I always have.

“No offence was intended by me saying that I discuss these issues with my wife. […] that is in no way an indication that these events had not already dramatically affected me.

“Equally, I accept that many were unhappy with the language that I used on the day of the protests. No offence was intended by that either. I could have chosen different words.”

He acknowledged “many Australians, especially women, believe that I have not heard them” and said “that greatly distresses me.”

He had “been doing a lot of listening over this past month”, which was “not for the first time”. He listed what he’d heard, ranging from women clutching their keys as weapons as they walked, to being talked over in boardrooms, staff rooms and even cabinets. There was much else that was “not OK”.

Morrison was at times highly emotional – as he was also in the joint parties meeting, where the official briefing noted he’d found it difficult to get out his first words in an address canvassing the recent times.

But amid his strong pitch at projecting empathy during his news conference, suddenly attack-dog Morrison broke the leash.

Sky News’ Andrew Clennell had asked, “if you’re the boss at a business and there had been an alleged rape on your watch and this incident we heard about last night on your watch, your job would probably be in a bit of jeopardy, wouldn’t it? Doesn’t it look like you have lost control of your ministerial staff?”

Instead of batting the question away – a tactic he’s adroit at – Morrison let fly.

This exchange followed.

PM: I will let you editorialise as you like, Andrew, but if anyone in this room wants to offer up the standards in their own workplaces by comparison I would invite you to do so.

Clennell: Well, they’re better than these I would suggest, Prime Minister.

PM: Let me take you up on that, let me take you up on that. Right now, you would be aware that in your own organisation that there is a person who has had a complaint made against them for harassment of a woman in a women’s toilet and that matter is being pursued by your own HR department.

This outburst was a bad misjudgment.

It wrongly implied the matter involved Sky News – Morrison had got his facts wrong about its nature. News Corp later put out a statement saying it was an exchange “about a workplace-related issue, it was not of a sexual nature, it did not take place in a toilet and neither person made a complaint”. The matter had now been resolved.

Morrison had distracted from, and undermined, the whole message he was trying to get through – that he understands and is focused on the problems women endure and on finding solutions.

One notable characteristic of Morrison is how his mood can turn on a dime. That reinforces the unsettling feeling one has of never being sure whether, on any particular day, we’re seeing the real deal, or the practised political actor.

– ref. View from The Hill: Scott Morrison opens door to Liberal quotas, but don’t hold your breath – https://theconversation.com/view-from-the-hill-scott-morrison-opens-door-to-liberal-quotas-but-dont-hold-your-breath-157693