Report by Dr David Robie – Café Pacific. –

|

| West Papuan envoy John Anari in New York … “moral and legal obligation” for the UN over West Papua. IMAGE: John Anari FB |

By DAVID ROBIE

A WEST Papuan envoy who was gagged while addressing the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues two years ago has been blocked again while trying to speak out.

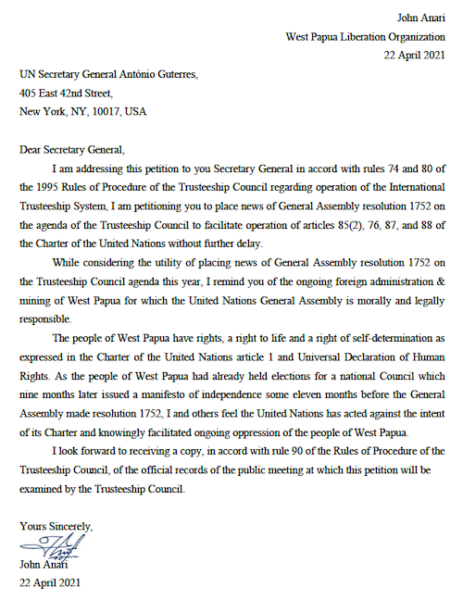

For six years, John Anari, leader of the West Papua Liberation Organisation (WPLO) and an “ambassador” of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), has been appealing to the forum to push for the Indonesian-ruled Melanesian region to be put on the UN Trusteeship Council.

He was speaking for the two groups combined as the West Papua Indigenous Organisation (WPIO), or Organisasi Pribumi Papua Barat, when he attempted to give his address at the forum last Thursday.

- READ MORE: West Papuan speaker ‘silenced’ when trying to raise UN agenda issue

- The PFII session – Anari gagged again

“I believe West Papua has been a UN Trust Territory since 1962 when the

General Assembly authorised [the] United Nations and Indonesia’s administration of West Papua,” he tried to say in his short declaration.

“I believe there is a moral and legal obligation for news of the authorisation, General Assembly resolution 1752 (XVII), to be placed on the agenda of the United Nations Trusteeship Council so that the Council can then ask the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for its advisory opinion on the proper status of West Papua in relation to the Charter of the United Nations.

“To restore United Nations awareness of the sovereign and human rights of our people, for

six years I have been asking this Permanent Forum [UNPFII] to advise the Economic and Social Council that it can and should place the missing agenda item on the agenda of the Trusteeship Council.

“Not only has this forum failed to relay our request, two years ago the moderator attempted to stop my reiteration of our request. This year I am also petitioning the Secretary-General to put news of the United Nations subjugation of West Papua on the agenda of the Trusteeship Council.

“If this forum will not relay our request, I ask you to explain to the international news media why this forum has not told the Economic and Social Council about General Assembly resolution 1752 under which West Papua is still suffering foreign administration and looting.”

The petition was presented to the Secretary-General, António Guterres.

Feed was silenced

A commentator on West Papuan affairs, Andrew Johnson, writes: “GAGGED Again ! ! ! John was allowed to introduce himself and the second he began saying what the United Nations does NOT want the public to hear, his feed was silenced!

“No doubt the UNPFII will claim it was a lucky gremlin, but John’s video feed was up and working and only went silent as he called attention to the United Nations own responsibility for the on-going oppression, deaths, and looting of West Papua for these past 59 years!”

After Anari was gagged again, a small group of Papuan protesters staged a Morning Star demonstration outside the UN headquarters in New York.

Attack on journalist Mambor

Meanwhile, Suara Papua has published an article exposing the “terror” campaign being waged against leading Papuan journalist Victor Mambor, the founder of Tabloid Jubi and who visited New Zealand in 2014.

A car that he owns which was parked on the road near his home in the Papuan capital of Jayapura was vandalised on the night of Wednesday, April 21.

The windscreen and side windows of Mambor’s Isuzu Double Cabin DMax were smashed by a blunt object.

The left-side front and back doors were also defaced with orange spray paint.

The Jayapura branch of the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) chairperson, Lucky Ireeuw, denounced what it regarded as a “terrorist” vandalism act over Mambor’s reporting on Papuan issues for Tabloid Jubi, The Jakarta Post and other media.

Tabloid Jubi and its website have frequently reported on human rights violations in Papua.

Before the vandalism, Mambor had suffered other attacks.

“Digital attacks, doxing, and disseminating a flyer on social media the content of which painted Tabloid Jubi and Victor Mambor in a bad light, playing people off against each other and threats of criminal attacks on the media and Victor personally,” said Ireeuw about the types of attacks.

He appealed to attackers to respect media freedom in the “land of Papua”.

.jpeg?1619180548)