Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Marcus Carter, Professor in Human-Computer Interaction, ARC Future Fellow, University of Sydney

The Australian government has announced a plan to ban children under the age of 16 from social media. With bipartisan support, it’s likely to be passed by the end of the year.

While some experts and school principals support the ban, the move has also been widely challenged by social media experts and children’s mental health groups.

In a press conference on Friday, Communications Minister Michelle Rowland suggested the ban would include platforms such as TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. An exemption would be considered for some services, such as YouTube Kids.

Some media reports raised concerns about online games like Minecraft, Fortnite and Roblox falling under the ban, because people can communicate with others on these platforms. Platforms like Xbox Live or the PlayStation Network would potentially be in scope, too.

A government spokesperson told Australian Community Media that a new, robust definition of “social media” would be forthcoming in the legislation. Games and messaging platforms are likely to be exempt, but we don’t know for sure at this stage.

As experts in children’s online play, we argue it would be a mistake to ban children from social games. Games are crucial to children’s social lives and learning, and for their personal growth and identity development.

What do young people gain from games?

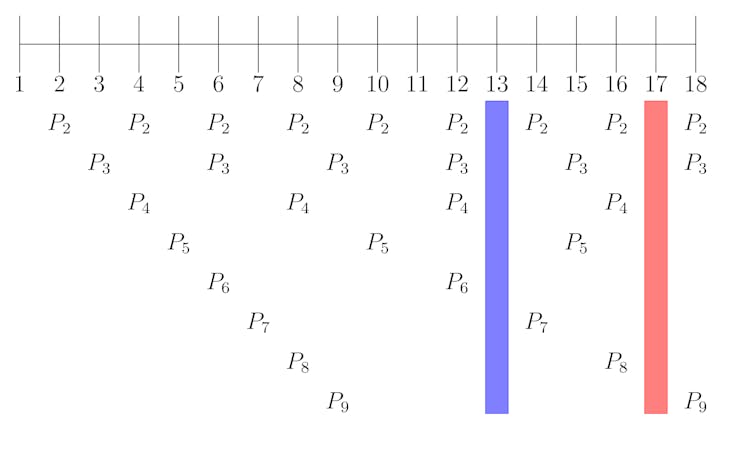

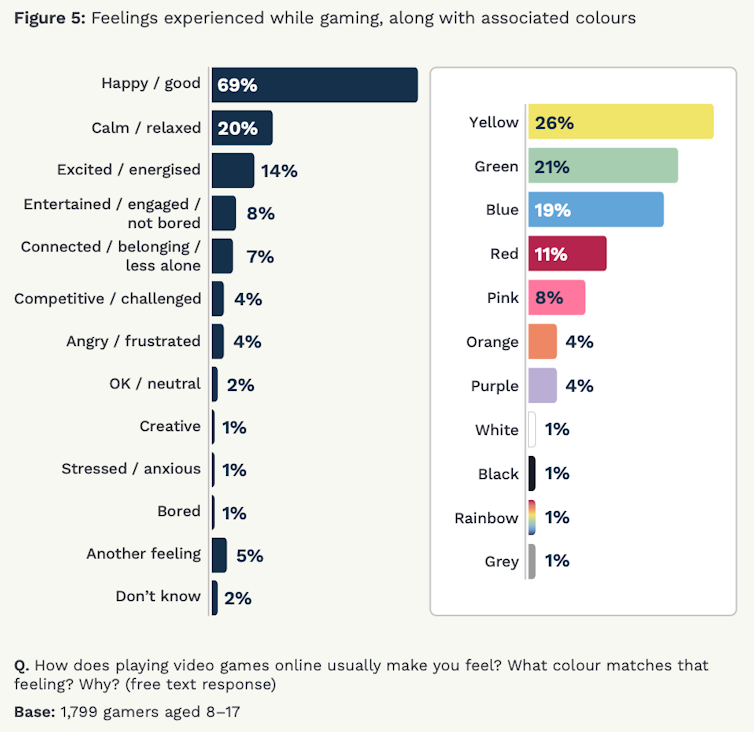

Games are widely popular, and 93% of Australian children aged 5–14 play videogames regularly. Two-thirds of children in Australia aged 9–12 play Minecraft at least once a month. Children and young people feel overwhelmingly positive about their online gameplay.

In a recent study by the eSafety Commissioner, over three-quarters of young gamers indicated that “gaming had helped them with skill development, such as learning something new, using digital technologies, solving problems and thinking faster”.

Minecraft has received particular attention for fostering creativity, collaboration and socially connecting young people.

In 2021, the Minecraft: Education Edition was being used in schools in 115 countries, including Australia. This version of the game contains free lessons on various subjects. In a study across six schools in Queensland, researchers found children who learned with Minecraft: Education Edition “overwhelmingly identified themselves as better mathematics students”.

eSafety Commissioner (2024) Levelling up to stay safe: Young people’s experiences navigating the joys and risks of online gaming, Canberra: Australian Government

Games offer rich spaces for play, which is critical for children’s identity formation, social lives and imagination. For instance, playing as a different character in an online game is an important form of playful identity exploration for children. (It’s valuable for adults, too.)

Two decades of research have also shown us that children derive enormous social benefits from playing digital games with other people. In a 2015 report by the Pew Research Center, 78% of teenagers said online games help them feel more connected to their friends.

A UNICEF review of research literature from earlier this year concluded that videogames can boost children’s wellbeing by making them feel competent, empowered and socially connected to others.

This is particularly important for vulnerable children. For instance, Autcraft, a parent-created Minecraft server for neurodivergent children, has been enormously successful in providing children with a comfortable and safe digital space to socially connect with their peers.

What about the risks?

However, games are not always safe spaces for young people.

Gaming culture is pervasively misogynistic, and games have played a role in mainstreaming far-right ideology by promoting meritocratic, racist and discriminatory ideologies.

Gaming platforms like Roblox – where over half of players are under the age of 13 – have also come under fire for not doing enough to protect their users from online grooming and child abuse material.

Increasingly, we’re also seeing the gamblification of games. In recent years, predatory monetisation models such as gambling-like lootboxes have become normalised.

In Australia, the Classification Board recently banned “in-game purchases with an element of chance” for children under 15. According to the definition, these are “mystery items players can use real money to buy, without knowing what item they will get”.

Incidentally, this decision demonstrates the ineffectiveness of blanket ban approaches. According to our yet-to-be-published research, numerous games with paid chance-based features such as lootboxes remain available on storefronts like Apple’s App Store, despite not complying with the new regulations.

A ban can’t make children’s online lives better

Just as all internet use isn’t bad, all games aren’t bad either. Parents may feel overwhelmed and under-informed about the videogames their children play, but bans can be easily circumvented. Australia’s eSafety Commissioner has expressed concerns that “some young people will access social media in secrecy”.

The risk is that a ban will take away the onus on these platforms to make them safer for children. Why design for users who aren’t legally allowed to be on the platform?

The government should be working in partnership with social media and online gaming platforms to ensure they are designed in children’s best interests, while allowing children the freedom to play and to access safer and richer digital lives.

![]()

Marcus Carter is a recipient of an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (#220100076) on ‘The Monetisation of Children in the Digital Games Industry’. He has previously received funding from Meta, TikTok and Snapchat, and has consulted for Telstra. He is a current board member, and former president, of the Digital Games Research Association of Australia.

Taylor Hardwick is employed under funding by the Australian Research Council (Future Fellowship #220100076; DECRA #240101275). She is a board member of Freeplay, a Melbourne-based independent games festival.

– ref. Online games should not be included in Australia’s social media ban – they are crucial for kids’ social lives – https://theconversation.com/online-games-should-not-be-included-in-australias-social-media-ban-they-are-crucial-for-kids-social-lives-243374