ER Report: Here is a summary of significant articles published on EveningReport.nz on June 10, 2025.

Why won’t my cough go away?

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By David King, Senior Lecturer in General Practice, The University of Queensland Mladen Zivkovic/Shutterstock A persistent cough can be embarrassing, especially if people think you have COVID. Coughing frequently can also make you physically tired, interfere with sleep and trigger urinary incontinence. As a GP, I have even

Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Illume is spectacle with heart and spirit, a thrilling manifestation of Country

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Erin Brannigan, Associate Professor, Theatre and Performance, UNSW Sydney Bangarra/Daniel Boud The stage is covered in stars that fill the depth of the space. When the 18 dancers slowly gather, they move through a night sky. This sky, and the scenes that unfold in Bangarra’s Illume are

Starlink is transforming Pacific internet access – but in some countries it’s still illegal

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Amanda H.A. Watson, Fellow, Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University Solomon aligning the Starlink dish on the roof of his friend’s home in Vanuatu. Paul Basant In the past few years, Starlink’s satellite internet service has become available across much of the Pacific. This has created

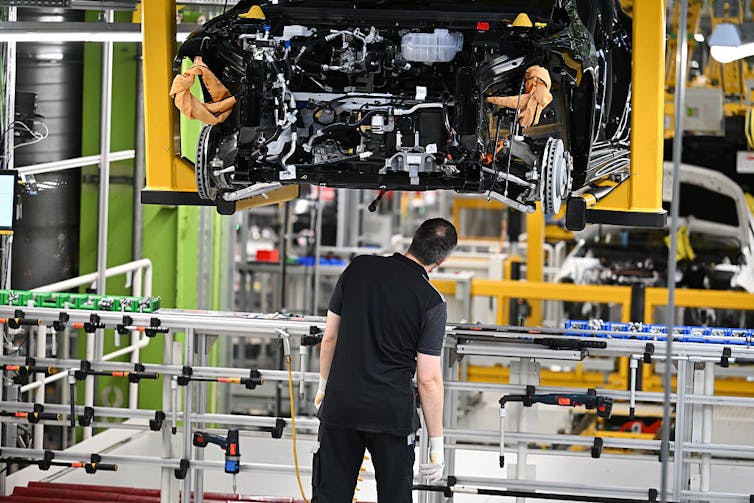

9 myths about electric vehicles have taken hold. A new study shows how many people fall for them

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Christian Bretter, Senior Research Fellow in Environmental Psychology, The University of Queensland More people believe misinformation about electric vehicles than disagree with it and even EV owners tend to believe the myths, our new research shows. We investigated the prevalence of misinformation about EVs in four countries

Keith Rankin Analysis – Remembering New Zealand’s Missing Tragedy

Analysis by Keith Rankin. Every country has its tragedies. A few are highly remembered. Most are semi-remembered. Others are almost entirely forgotten. Sometimes the loss of memory is due to these tragedies being to a degree international, seemingly making it somebody else’s ‘duty’ to remember them. This could have been the case with the Air

A 10-fold increase in rocket launches would start harming the ozone layer – new research

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Laura Revell, Associate Professor in Atmospheric Chemistry, University of Canterbury Han Jiajun/VCG via Getty Images The international space industry is on a growth trajectory, but new research shows a rapid increase in rocket launches would damage the ozone layer. Several hundred rockets are launched globally each year

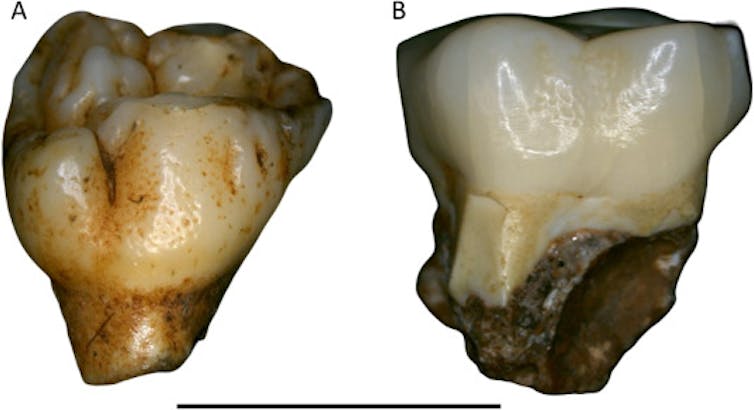

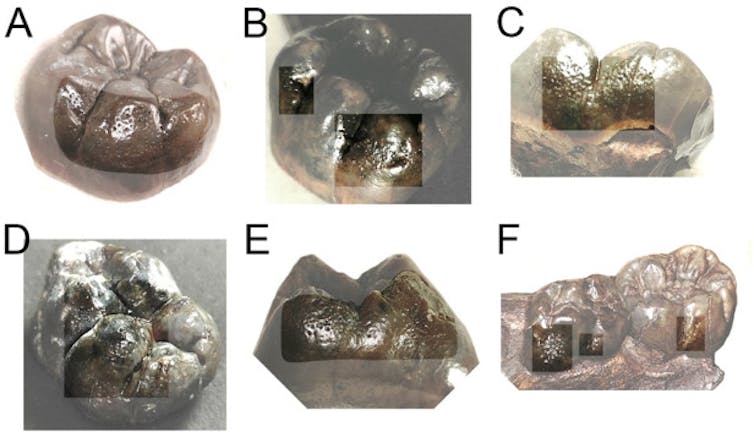

For the first time, fossil stomach contents of a sauropod dinosaur reveal what they really ate

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Stephen Poropat, Research Associate, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University Artist’s reconstruction of Judy. Travis Tischler Since the late 19th century, sauropod dinosaurs (long-necks like Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus) have been almost universally regarded as herbivores, or plant eaters. However, until recently, no direct evidence –

The Racial Discrimination Act at 50: the bumpy, years-long journey to Australia’s first human rights laws

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Azadeh Dastyari, Director, Research and Policy, Whitlam Institute, Western Sydney University On June 11, Australia marks 50 years since the Racial Discrimination Act became law. This important legislation helps make sure people are treated equally no matter their race, skin colour, background, or where they come from.

Fake news and real cannibalism: a cautionary tale from the Dutch Golden Age

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Garritt C. Van Dyk, Senior Lecturer in History, University of Waikato The Corpses of the De Witt Brothers, attributed to Jan de Baen, c. 1672-1675. Rijksmuseum The Dutch Golden Age, beginning in 1588, is known for the art of Rembrandt, the invention of the microscope, and the

Some economists have called for a radical ‘global wealth tax’ on billionaires. How would that work?

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Venkat Narayanan, Senior Lecturer – Accounting and Tax, RMIT University Rudy Balasko/Shutterstock Earlier this year, I attended a housing conference in Sydney. The event’s opening address centred on the way Australia seems to be becoming like 18th-century England – a country where inheritance largely determines one’s opportunities

Australia’s whooping cough surge is not over – and it doesn’t just affect babies

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Niall Johnston, Conjoint Associate Lecturer, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney Tomsickova Tatyana/Shutterstock Whooping cough (pertussis) is always circulating in Australia, and epidemics are expected every three to four years. However, the numbers we’re seeing with the current surge – which started in 2024 – are higher than

As livestock numbers grow, wild animal populations plummet. Giving all creatures a better future will take a major rethink

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Clive Phillips, Adjunct Professor in Animal Welfare, Curtin University Toa55/Shutterstock As a teenager in the 1970s, I worked on a typical dairy farm in England. Fifty cows grazed on lush pastures for most of their long lives, each producing about 12 litres of milk daily. They were

Johannesburg’s problems can be solved – but it’s a long journey to fix South Africa’s economic powerhouse

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Philip Harrison, Professor School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand South African president Cyril Ramaphosa met senior leaders of Johannesburg and Gauteng, the province it’s located in, in March 2025 to discuss ways to arrest the steep decline in South Africa’s largest city. Ramaphosa announced

Albanese says the government’s focus on delivering commitments is essential to reinforce faith in democracy

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra Prime Minister Anthony Albanese says his second term government is “focused on delivery” of its commitments, declaring this is important not only for the economy but also for Australians’ faith in our democracy. In a speech to the National Press

Why Israel’s ‘humane’ propaganda is such a sinister facade

COMMENTARY: By Cole Martin in Occupied Bethlehem Many people have been closely following the journey this week of the Madleen, a small humanitarian yacht seeking to break Israel’s illegal blockade of Gaza with a crew of 12 on board, including humanitarian activists and journalists. This morning we woke to the harrowing, yet not unexpected, news

Trump has long speculated about using force against his own people. Now he has the pretext to do so

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Emma Shortis, Adjunct Senior Fellow, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University “You just [expletive] shot the reporter!” Australian journalist Lauren Tomasi was in the middle of a live cross, covering the protests against the Trump administration’s mass deportation policy in Los Angeles, California. As

Palestinian supporters in NZ accuse Israel of ‘state piracy’ and condemn silence

Asia Pacific Report Israel’s military attack and boarding of the humanitarian boat Madleen attempting to deliver food and medical aid to the besieged people of Gaza has been condemned by New Zealand Palestinian advocacy groups as a “staggering act of state piracy”. The vessel was in international waters, carrying aid workers, doctors, journalists, and supplies