REVIEW: By Philip Cass, editor of Pacific Journalism Review

One of the joys of travelling the world and collecting books is the historical oddities that turn up in the most unexpected places.

I have a splendid copy of the complete works of Shakespeare dating to the Second World War, completely re-set, so the frontispiece notes, due to the original plates having been “destroyed by enemy action”. One wonders at the perfidy of the Luftwaffe in trying to blow up the Bard.

I have a copy of Grove’s encyclopaedia of music from the 1930s which notes with disdain that attempts to make jazz respectable by using an orchestra have failed—and this written several years after Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The same volume also contains a section on the influence of Jews in classical music, noting such important ‘Hebrew’ composers as Mahler.

Both these volumes came from a secondhand bookseller near the bus station in Suva: relics, I suppose, of a long departed British colonial administrator.

Each of these volumes is a window into the past and into attitudes and ideas that have long vanished.

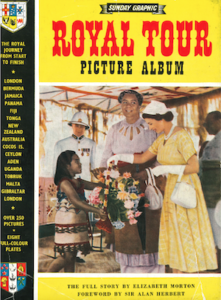

In the year of the Platinum Jubilee of the late Queen Elizabeth II—who died yesterday aged 96 after a 70-year reign—it was therefore timely to find a copy of the Royal Tour Picture Album, a lavishly illustrated record of her 1953 tour of the Commonwealth in my local Salvation Army shop.

The 1953 tour seems to have been a strange affair, a tour of places rarely visited by royalty alongside some more important but equally far-flung outposts of the Commonwealth. It was rather like Iron Maiden playing in Christchurch or Caracas.

Pacific and other places

The Queen and Prince Philip visited Bermuda, Jamaica, Panama, Fiji, Tonga, New Zealand, Australia, what was then Ceylon, Aden, Uganda, Tobruk (Libya), Malta and Gibraltar.

The African segment seems to have been beset by security issues and Britain would eventually be expelled from Aden and Libya, where the Queen paid tribute to the defence of Tobruk during the Second World War.

What is intriguing is the concentration on the small island states in the Caribbean and the Pacific, places which did not, at the time, seem to have afforded much material benefit to the UK (although the Fijian soldiers who served in the British army and the Windrush migrants might argue otherwise), but which could be relied upon to provide a loyal, colourful and exotic welcome.

It is the Pacific that takes up most of the pages here. There are some splendid colour plates (one suspects some of them are actually hand tinted) showing, among other things, Her Majesty and the Secretary for Fijian Affairs, Ratu Lala Sukuna, in Albert Park in Suva, surrounded by Fijians with their gifts for the visitors—50 newly killed pigs, 50 cooked pigs, 10 tons of bananas and 50 metres of tapa cloth.

It is the depictions of the local people that intrigue after so many decades. Some of the Indigenous peoples, like the Tongans, are well defined (at least in the somewhat patronising terms of the day), others are projected as members of a happy, multi-racial Commonwealth (the various inhabitants of Fiji) and others, like the First Nations peoples of Australia are very awkwardly presented, with little or no information or explanation about who they are or why they are there. Given the things we know now, some of the images raise disturbing questions to which we may never know the answers.

It is unclear whether the author, Elizabeth Morton, accompanied the tour or simply worked from a pile of press releases and newspaper clippings. The book was co-produced with the Sunday Graphic, which closed in 1960, so she may have worked for that masthead.

Whatever the case, she was clearly eager to present Fiji as a multi-racial success story. While we are told that the royal vessel, the SS Gothic, was greeted by canoes manned by ‘fuzzy haired warriors’ we are also told that ‘Fijians, Indians, Chinese and Europeans’ all cheered the Queen.

Lautoka’s ‘tremendous welcome’

Later they visited Lautoka where they received ‘a tremendous welcome from the Indian sugar-cane workers’. Alas, it would only take a few more decades for that multicultural vision to be shattered by the first of the coups that have bedevilled Fiji

From Fiji, Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh flew to Nuku’alofa in a TEAL Solent Mk IV flying boat, the Aranui, which is now in the MOTAT aviation collection in Auckland.

Despite only visiting for two days, the royal visitors were given a hearty welcome.

She and the Duke were greeted by Queen Salote, who had entranced the British when she visited London for Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. When the Tongan monarch rode in an open carriage oblivious of the rain, her fortitude drew the admiration of the crowd and prompted both Noel Coward and Flanders and Swan to make jokes that are probably unrepeatable today.

Despite preserving its independence, Tonga had strong ties with the United Kingdom. During the Second World War, when the then Princess Elizabeth was driving an ambulance, Queen Salote raised enough money to buy three Spitfires for the RAF.

After being greeted at the wharf by Queen Salote, the Queen and the Duke drove through the rain into the capital where people from all over the kingdom, including its remotest islands, gathered to greet her.

Ex-servicemen marched through the streets and at the mala’e the British visitors were waited on by members of the Nobility as they and 2000 guests tucked into a banquet of pork, chicken crayfish, lobsters, yams and pineapples.

A sipi tau (the Tongan equivalent of the haka) was given in honour of the visitors.

That night they slept at the royal palace and were wakened in the morning by a serenade of nose flutes.

Overflowing church

After breakfast they attended service in the Wesleyan church that was full to overflowing.

In her speech, Queen Elizabeth said: ‘Never was a more appropriate name bestowed on any lands than that which Captain Cook gave to these beautiful islands when he called them The Friendly Islands.’

The photographs accompanying the report are of the kind we have become used to: The Queen and her party enjoying local hospitality, receiving gifts and inspecting local curiosities, including Tui Malila, the tortoise said to have been presented by Captain Cook in 1777. The tortoise died in 1966.

And how were the Tongans presented? It is worth reading, 70 years later, Morton’s description:

The Tongans are a simple, happy, devout people. They share their fervent loyalty between their own Queen and the Sovereign Head of the Empire and Commonwealth which since 1900 has protected their 1000 year old independence. Their land is rich and fertile, their seas teem with fish; for longer than they can remember there has never been poverty or unemployment in their paradise. Queen Elizabeth II came to them as their friend from afar whose navies guard their shores and whose peoples buy all the bananas, copra and coconuts they produce.

They welcomed the Queen and her husband with sincere and abandoned joy and gave them a feast that was fabulous in its lavishness. But before this began there was a simple little ceremony on the quay at Nuku’alofa shortly after the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh landed. Five-year-old Mele Siuilikutape, granddaughter of Queen Salote, came shyly forward and, with all the dignity and grace of her ancient race, presented the friend of Tonga with a basket of wild flowers.

This passage lays out a vision that was very familiar, an Island paradise presided over by a wise local ruler loyal to Britain and a people forever grateful for the protection of the Royal Navy. Was it only slightly more than 50 years since Kipling had prophesied: ‘Far-called, our navies melt away?’ In another 30 years Britain would barely be able to scrape together enough ships to rescue the Falklands from the Argentine invaders.

Queen Elizabeth visited Tonga again in 1970 and 1977.

‘Cherished memories’

When Prince Harry visited Tonga in 2018 he read a message from his grandmother: ‘To this day I remember with fondness Queen Salote’s attendance at my own Coronation, while Prince Philip and I have cherished memories from our three wonderful visits to your country.’

From Tonga, the Queen travelled on to New Zealand, where, according to Morton, ‘the Maoris, once the most warlike and adventurous of the Polynesian races, now live in peace and understanding with the people of British stock’.

Later, she writes: ‘The Maoris gave their first vociferous welcome at Waitangi, an historic spot on the placid waters of the Bay of Islands. Here in 1840 the Maori chiefs met Captain William Hobson—who became the first Governor of New Zealand-and signed a treaty acknowledging Queen Victoria as their sovereign.’ It is possibly not too much to suggest that some modern readers might bridle at this interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi.

From New Zealand, the Queen travelled on to Australia. Here too we have a picture of a predominantly white nation, but unlike New Zealand the Indigenous people remain in the background; if not unacknowledged then certainly unexplained. Clumsy as the writing about Māori might seem to us today, it is a reflection of the Pākehā view of the day and Māori representatives are present and clearly indicated in several photographs.

In Australia, the identified Indigenous face practically disappears. Here is a colour photograph of ‘fearsome looking Torres Straits Islanders armed with bows and arrows and wearing elaborate feather head dresses’ providing a guard of honour in Cairns.

Here is a group of Aborigines from the Northern Territory who had been shipped to Toowoomba in Queensland where they ‘performed native dances’. Here are two Aboriginal girls in ‘immaculate white dresses’ curtseying to the Queen, but they have their backs to the camera. They have no identity. In the background an Aboriginal dancer looks on.

Here, though, is six-year-old Beverley Joy Noble, from the Kurrawong Native Mission in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, presenting a bouquet. One wonders whether she was one of the Stolen Generation.

There are other, unexplained photographs. There is a picture of the royal party in Busselton in Western Australia where they were greeted by a Boy Scout troop—most of whom seem to be Indigenous Peoples, but nothing is said about who they are or how a multi-racial troop evolved.

Unexplained picture

And last but not least, there is an entirely unexplained picture of the late Queen reviewing ‘soldiers and sailors from Australia’s Island Territories’. These vaguely determined people are clearly members of the Pacific Islands Regiment (the PIR) from what was then the Territory of Papua and New Guinea.

The Royal Tour Picture Album is a glimpse into a world that simply never existed for much of today’s population. However, this does not make the book simply a curiosity. Indeed, for the curious, the book is a joy because of what it contains. It preserves images and ideas and views that need to examined, not just for their historical value, or as a mark of how far attitudes have changed, but as a warning that in 70 years our descendants will look upon our own world—and us—and wonder with equal puzzlement at why or how we behaved and thought as we do.

Dr Philip Cass is editor of Pacific Journalism Review. This review is republished from PJR in a partnership and was written and published before the death of Queen Elizabeth II on 8 September 2022 aged 96 after a remarkable reign of 70 years.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz