Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Scott Davie, Lecturer in Piano, School of Music, Australian National University

Kent G Becker/flickr, CC BY-SA

On June 25 1910, Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird opened to acclaim at the Paris Opéra. The success propelled its composer, then aged 28, to international prominence, a position of influence he would retain for six decades.

The ballet’s myth-like storyline features a magical Firebird, who helps a young prince rescue a coterie of princesses from Kashchey, an evil sorcerer.

Based on the eponymous bird of Russian folklore, it has ultimately propagated some myths of its own – relating to the artistic ideals of the team who created it, and the narrative’s historical accuracy.

Most crucial, though, is the composer himself who, through successive elaborations of his own biography, engaged in myth-making on an extensive scale. Notable for what Stravinsky expert Richard Taruskin terms his “celebrated mendacity”, questions have lingered as to whether certain of the composer’s early musical ideas were as original as they seemed.

Conservative ‘modernists’

After The Firebird, Stravinsky’s early career was bolstered by the triumph of his next two works: Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. Given the impact of the last work in particular, it is customary to note Stravinsky’s pivotal influence on the development of musical modernism.

Yet in 1910, he was a largely untested novice. The Firebird was a production of the Ballets Russes, newly formed by its director, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev. For over a decade, Diaghilev had been a leading member of a group known as “Mir iskusstva” (World of Art), the title of their short-lived magazine.

WIkimedia Commons

Their artistic ideals, however, were far from modern. A collection of conservatives, many were from aristocratic backgrounds with a tendency toward romantic nationalism. They were aligned against both the “realist” modernism of the previous generation, and the evolving spiritual modernism of fellow Russian composers like Scriabin. Their principles were those against which socialists would soon react.

In a series of ventures for Parisian audiences from 1906, Diaghilev looked to Russia’s past for his sources. After discovering how expensive opera was to produce, he settled exclusively on ballet from 1910. Again, however, his musical choices were initially conservative.

Repurposed myths

Magical birds are not without precedent in folklore, having featured in the childhood tales of many countries, such as Germany, where a similar creature appears in Grimm’s The Golden Bird.

Yet in Russia, the Firebird had a special significance, emerging as a nationalist symbol over the latter decades of the 19th century. Characterised as a bird of great beauty, it brought peril to those who tried to catch it or steal its glowing feathers.

In the Ballets Russes production, however, far from causing misfortune, when the young prince catches the Firebird it actually helps him.

Historians have noted the story is similar to lines from Russian poet Yakov Polonsky’s children’s poem, Winter Journey (1844). Yet the synopsis evidently is a conflation of two separate folk tales, developed by Mir iskusstva members as an export vehicle for foreign audiences.

Led by the choreographer Mikhail Fokine, the stories were repurposed by Alexandre Benois and Alexander Golovin, both important contributors to Ballets Russes design, and Nikolai Tcherepnin, the composer originally selected to write the Firebird’s music.

In short, the popular folk tale of Ivan-Tsarevich, and his quest for a beautiful princess (in which the Firebird features tangentially), was blended with a separate folk tale about the evil, immortal Kashchey, who dies at the hand of a prince who possesses a magical egg.

‘New’ music

Fokine, who by typical accounts was a difficult choreographer to work with, likely caused three composers to exit or decline the project. Hence, the fortuitous opening for Stravinsky, a student of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, the elder statesman of Russian music whose most progressive works were little known in the West.

Flickr

According to Fokine’s autobiography, Stravinsky sat at the piano, improvising and accompanying as the choreographer first developed his ideas for the work. If this account is accurate, never again would the composer allow himself to appear so ancillary to the creative process.

The most noticeable element of Stravinsky’s score is the way harmonious, tonal music is given to the mortal characters – Ivan-Tsarevich and the princesses – while chromatic, non-tonal music underscores the supernatural others.

This clever device is, in fact, a Russian tradition. The source can be traced as far back as Mikhail Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842), where a strikingly non-tonal descending scale depicts the supernatural abduction of a bride from her traditional (and tonal) wedding feast.

Stravinsky, an observant student, had closely scrutinised the innovative, and increasingly non-tonal, musical works of Rimsky-Korsakov, where the device was also prevalent.

He elaborated on one of Rimsky’s theories to create what has been called a “ladder of thirds”. Analysis from recent decades by musicologist Taruskin, has detected this schematic underpinning large portions of The Firebird.

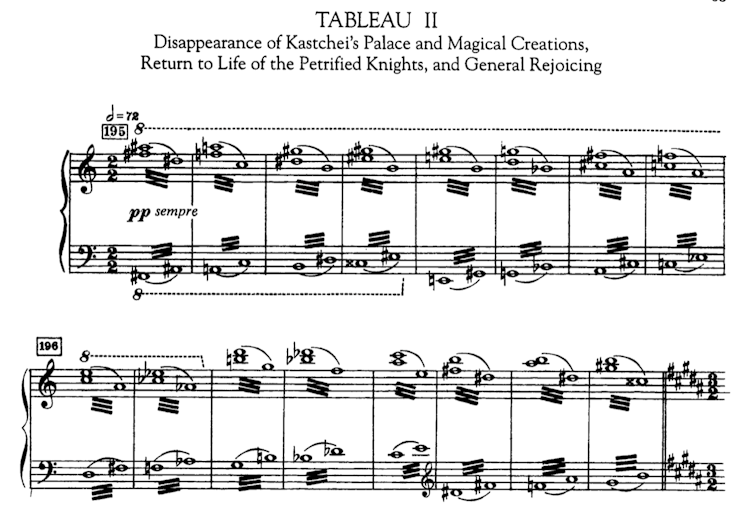

The weirdly alternating pattern of thirds generates the supernatural music of the introduction, the Firebird’s chromatic “swirls” and Kashchey’s motifs.

Screenshot/Stravinsky

Most beautifully, it also provides the hushed musical transition from the underworld to the final tableau, where Ivan-Tsarevich and the princesses celebrate victory.

Yet for the mortal, tonal characters, Stravinsky, in places, incorporates folk melodies, another popular tradition among Russian composers.

Contrast Stravinsky’s setting of a folk-tune in the Khorovod of the Princesses from The Firebird, with Rimsky-Korsakov’s setting of the same melody in his Sinfonietta.

Stravinsky was always squeamish when questioned about his use of folk melodies, even flatly denying it. Yet as later analysis has shown, other works of this period, such as The Rite of Spring, feature them in abundance.

The influence of Rimsky-Korsakov can be noted in other ways, too, not least in his own opera about the very same Kashchey (1902), and his final opera, The Golden Cockerel (1908), also, tellingly, about a magical bird.

Indeed, if one wanted to really push the point, mention could be made passive of the notorious similarity of the Mt Triglav episode from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet Mlada to Stravinsky’s Danse infernal

in The Firebird where, in short, the plagiarism seems breathtaking.

The ‘hit’

But that would miss the most important point: for audiences in the West, The Firebird was a hit. These fantastical tales of Russia’s past were woven, almost accidentally it seems, with a musical work that on foreign soil appeared unexpectedly modern.

The belated development of Russian music had for a century remained relatively hidden to the rest of the world. And after a long gestation, it was Stravinsky who revealed many of its treasures.

It was as if a baton had passed from one generation to the next, through the smallest of steps. The real genius of Stravinsky is that he was to run so far with it, and so quickly.

![]()

Scott Davie does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Decoding the music masterpieces: Stravinsky’s The Firebird – https://theconversation.com/decoding-the-music-masterpieces-stravinskys-the-firebird-161582