By Walter Zweifel, RNZ Pacific reporter

While a Paris roundtable about the legacy of nuclear tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls is eagerly awaited by the French Polynesian government, the nuclear veterans organisations wonder whether the victims are really represented at the talks. Like every year, they will instead mark tomorrow — July 2 — as the day in 1966 when France detonated its first nuclear bomb in the South Pacific. Walter Zweifel reports.

A high-level roundtable on France’s nuclear legacy in French Polynesia is being held in Paris this week, aimed at “turning the page” on the aftermath of the weapons tests.

Between 1966 to 1996, France carried out 193 tests in the South Pacific, yet 25 years later there are still outstanding claims for compensation and the test sites remain no-go zones monitored by France.

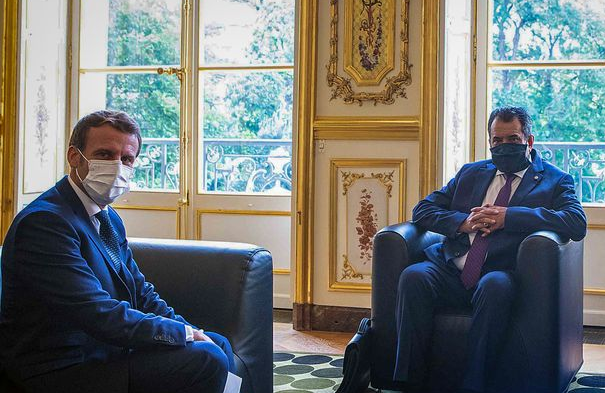

The two-day Paris meeting was called by the French president Emmanuel Macron in April shortly after a new study about a 1974 atmospheric weapons test caused another wave of outcry.

Analysing declassified French documents, the study Toxique by the news website Disclose concluded that the fallout affected the entire population and not only the immediate testing zone around Moruroa as the public had been led to believe.

Macron’s initiative to put the recent history on the table has been welcomed by French Polynesia’s president Edouard Fritch, but has been dismissed by the opposition, nuclear veteran groups and the dominant Maohi Protestant Church, which will stay away, saying the delegation from Tahiti lacks credibility and legitimacy.

For Fritch, the problems thrown up by the nuclear test era have been discussed with French politicians for the past 25 years but he says it is Macron who at last wants to deal with this “pebble in the shoe” in the relationship with Tahiti.

This harks back to Macron’s 2017 presidential election campaign when his team promised Tahitians that Paris would assume key responsibility for health care and to pay in full for the medical costs incurred by those suffering from radiation-induced illnesses.

Tests’ impact on health, environment

Fritch told media that the upcoming talks should bring ‘truth and justice’, with an agenda looking at the tests’ impact on health and the environment, and the financial costs.

The Tahitian delegation also wants France to acknowledge its nuclear legacy in the constitution.

Fritch said he would “ask the President of the Republic to give us a precise timetable and above all to send us competent people in the matters that will be discussed”.

Accompanying Fritch is a representative of the Territorial Assembly and the territory’s members of the French legislature, such as Lana Tetuanui, as well as employer and union delegates.

Among the French participants will be the health minister but the defence minister is not certain to attend.

French Polynesia’s former president Gaston Flosse, who for decades defended France’s testing regime, was not invited.

Reflecting the simmering dissonance in Tahiti, the pro-independence Tavini Huiraatira party of Oscar Temaru rejected the invitation to Paris outright, labelling the planned talks a sham.

Temaru said any such talks should not be held in the capital of the colonising power, but rather in New York under the auspices of the United Nations.

While France refuses to acknowledge the 2013 UN decision to reinscribe French Polynesia on the decolonisation list, Temaru insists that “the right of peoples to self-determination is a sacred right, and there is no mixing the sacred and the vile, that is money. Our people are not for sale, Mā’ohi Nui is not for sale.”

The main nuclear test veterans organisation, Moruroa e tatou, decided to boycott the talks.

Its leader Hiro Tefaarere said that after 50 years of people suffering from the test legacy, those going to Paris put money at the forefront of their demands and not ethics.

He said Fritch would not have joined the roundtable had not it been for the release of Toxique which identified the French state’s “secrecy, lies and negligence”.

‘Crime against humanity’

Rejecting the French invitation, the Māohi Protestant Church, which is the main denomination in Tahiti, has in turn invited Macron to attend its synod when he is expected to visit Tahiti in the next few weeks.

The head of the church, Francois Pihaatae, said that by going to Paris, they would have the “wool pulled over their eyes”, but once Macron was in Tahiti the presence of the local people would create a counterweight.

The church has been critical of the French state, saying it proceeded with the tests in full knowledge of the impact of nuclear testing since before 1963.

Both the church and Temaru’s Tavini Huiraatira Party alleged that this amounted to a crime against humanity.

Three years ago, they announced that they had taken their case to the International Criminal Court (ICC), but it is not known if the court has accepted jurisdiction for their complaint.

Paris roundly rejected the claims, condemning what it called the misuse of the court’s international jurisdiction for local political purposes.

The French High Commissioner Rene Bidal said at the time the definition of a crime against humanity centred on the Nuremburg trials after the Second World War and referred to killings, exterminations, and deportations.

Soon after making his charge, Temaru was forced out of office over an election campaign irregularity, which his Tavini Huiraatira party said was orchestrated by France to “politically assassinate” him in retribution for the ICC case.

Until 2009, France claimed that its tests were clean and caused no harm, but in 2010, under the stewardship of Defence Minister Herve Morin, a compensation law was passed.

Over a decade, it proved to be a source of frustration because most claimants, who suffered from any of the 23 recognised types of cancer, failed with their applications.

This prompted a loosening of the eligibility criteria and then again a tightening, leaving it still open for further amendments.

French Polynesia’s social security agency CPS has repeatedly called on the French state to reimburse it for the medical costs caused by its tests.

It said that since 1995 it had paid out US$800 million to treat a total of 10,000 people suffering from cancer as the result of radiation.

Temaru said the money was a debt, pointing out that if a crime was committed it was not up to the victims to have to pay.

Risks around Moruroa

The question of the tests’ lasting intergenerational effects remains unanswered.

In 2018, a study was planned after the former head of child psychiatry in Tahiti, Dr Christian Sueur, reported pervasive developmental disorders in zones close to the Moruroa weapons test site.

The findings — reported in the Le Parisien newspaper — caused an uproar in Tahiti and Fritch accused Dr Sueur of causing panic.

The psychiatrist had reported that a quarter of children he treated for pervasive developmental disorders had intellectual disabilities or deformities which he attributed to genetic mutations.

However, three years on a study by a geneticist is yet to be commissioned.

Calls for a clean-up of the Moruroa test site continue.

Although France stopped its weapons tests in 1996, it has refused to return the excised atoll to French Polynesia and declared it a no-go zone.

The Tavini’s Moetai Brotherson, who is also a member of the French National Assembly, said France might lack either the technology or the financial means to remove radioactive sediments.

He also said the cracks on Moruroa were a concern which might explain why France’s biggest investment in the region is the US$100 million Telsite monitoring system against a possible tsunami.

There are fears the atoll could collapse as result of the more than 140 underground nuclear blasts.

Plans for a memorial to be built in Pape’ete have had lacklustre support from those who keep mistrusting France.

While the roundtable is eagerly awaited by the French Polynesian government, the nuclear veterans organisations wonder whether the victims are really represented at the talks.

Like every year, they will instead mark tomorrow — July 2 — as the day in 1966 when France detonated its first nuclear bomb in the South Pacific.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz