ANALYSIS: By Sara Niner

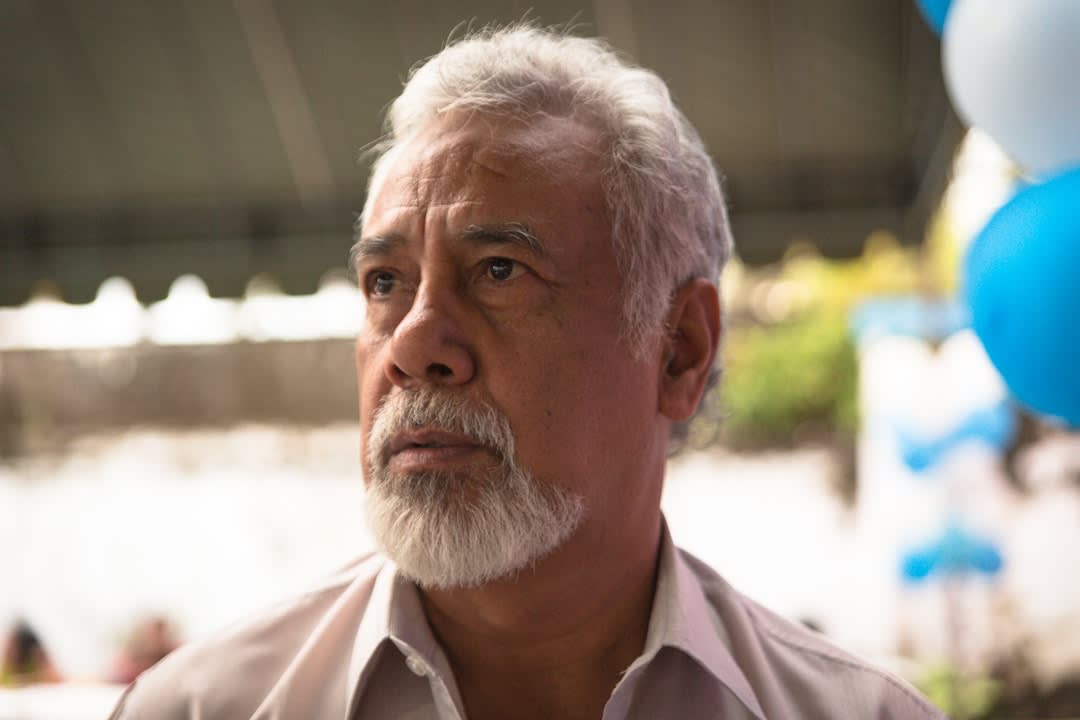

Xanana Gusmao’s recent contrived jovial participation in the birthday celebrations of “self-professed” paedophile and defrocked foreign priest Richard Daschbach has shocked many of his supporters, not least his Australian former wife and three Timorese-Australian sons who have publicly condemned the visit and written apologetic letters to the young women who were due to give evidence against Daschbach in court this week.

At the very well-publicised “birthday party” held in the home of a diehard Catholic supporter, Gusmao embraced and hand-fed Daschbach birthday cake, and tipped champagne into his mouth.

The visit has been interpreted as a heavy-handed attempt to whitewash Daschbach’s ruined reputation just before the court case commenced, and intimidate the prosecution, and the young witnesses who are in hiding due to just this sort of pressure.

In blatantly favouring the reputation of an ex-priest over the safety and wellbeing of his alleged victims, these male elites demonstrate a fundamental element of patriarchy defined as: “… a set of social relations between men, which have a material base, and which, through hierarchy, establish or create interdependence and solidarity among men that enable them to dominate women”. (Hartmann, 1979, p11).

Why would Gusmao bother?

It can be explained by long-term patriarchal relationships between particular conservative priests and resistance leaders such as Gusmao, and the almighty political, social and spiritual power of the Catholic Church in Timor-Leste to co-opt political leaders.

Gusmao’s visit is said to have been to honour the ex-priest’s role in the struggle for independence. Yet it also has to do with the low status and lack of power of poor young females, orphans with no one to protect them, and the phenomenal combined power of the clergy and the heroes of the resistance – when these patriarchal forces come together in Timor, very few can contest their will.

Yet some are speaking – and have spoken out – including Gusmao’s Australian sons; more progressive clergy; journalists and their professional association; lawyers representing the victims and others from the legal community; the women’s organisations protecting the alleged victims; and ordinary citizens expressing horror on social media, where the topic has been discussed.

This list will continue to grow. These are the new progressive forces in Timor-Leste contesting the power of the old patriarchal forces.

Daschbach has openly confessed more than once to the crimes, and was expelled from the priesthood and Catholic Church after an investigation in 2018. Since then, the justice system in Timor has struggled with prosecuting the case due to the interference of local religious supporters of the ex-priest, and a lack of appetite for arresting and imprisoning a priest.

While the problem is a global one and not well dealt with anywhere, to understand why this has happened in Timor, some appreciation for the particularities of the Catholic Church there is required.

As a Catholic country, with more than 90 percent adherence, the church wields enormous social, political and spiritual power, and priests are revered as God on earth. Daschbach was treated as a “demigod” with “magical abilities” and a “direct line to Christ”.

People still bow down or kneel and kiss the ring of priests to greet them. Others are simply too afraid to speak out for fear of excommunication, and the social, political and spiritual implications of this for themselves and their families.

Due to the Indonesian occupation, the Catholic Church in Timor-Leste remains “wedded to ideas of hierarchy and obedience” largely unaffected by liberal changes introduced by the second Vatican Council.

The deeply conservative church provides the moral and spiritual underpinning of an unequal gender regime. This leads to the significant conservative impact of religious discourses on gender roles and relationships, sex, reproduction, and homosexuality.

A woman activist explains that Catholic priests will not accept “modern” ideas about gender equality, or address sexual abuse and violence: “… they are more inclined to men’s perspectives and […] the patriarchal mentality“.

The church’s religious doctrines heavily influence government policy, leading to a lack of sex education in schools and reproductive healthcare, including the use of condoms as a protective measure to avoid pregnancy and disease, resulting in many avoidable deaths.

The inner circle: The Catholic Justice and Peace Commission

While the Bishop of Dili has urged all Catholics to respect the Vatican’s decision to expel Daschbach, there’s a hardcore group within the church, led by lawyers from the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission, who have led his campaign of support.

Commission members even visited the orphanage where the abuse is alleged to have occurred, and spoke to potential victims and witnesses, as well as parents, police, and lawyers.

In a report, they accuse the Timorese judicial and police authorities and organisations that have supported victims of being a “justice-mafia” and, perversely, of “collective sexual abuse” (for conducting medical examinations), “exploitation of underage girls”, and “human trafficking” (for moving them to a safe house).

By disclosing the names of alleged victims, witnesses, and the suspect himself, one local lawyer says they have broken the law. The Archbishop swiftly sacked the president of the commission.

The gender challenge

Gender relations apparent in contemporary Timorese society are the result of complex political and historical circumstances.

The dominance of men in Timorese history and politics, and the legacy of militarisation and conflict with neighbouring Indonesia during the national struggle for independence (1974-1999) are significant issues in contemporary Timorese society that pose enormous challenges for the nation.

As in most post-conflict societies, the effects of militarisation on society have not been adequately dealt with. I have argued that it was this that led to internal violence among the male political leadership resulting in a national crisis in 2006, and shattering of national reconstruction and development.

A tough and brutalised masculinity has significant damaging effects for the young men who try to live up to it, but also others such as the LGBTI community who face persecution and discrimination.

The negative influence of the Catholic Church on attitudes to homosexuality highlights the crucial work needed to combat the solid wall of intolerance built by conservative forces.

A recent secret research report found that young women have a lack of knowledge, choice, and agency in first sexual experiences leading to sexual abuse. Young women were often unaware that their consent was even required for sex.

In another study, between 20 to 30 percent of men admitted to rape, and in another acceptance of public sexual harassment and forced sex was clear. This may be linked to even higher levels of sexual abuse experienced by men. A shocking 42 percent of the men surveyed in 2016 reported being sexually abused before the age 18.

More powerful men

While research data does not yet exist on perpetrators of male victims, it seems likely that more powerful boys or men from within their own families, communities, clubs, schools and churches were the perpetrators.

The patriarchal hierarchies of power within institutional settings must be challenged if vulnerable people, including women and children, are to be protected – and not just in Timorese society.

There is no disputing that Gusmao completed a Herculean task in leading the East Timorese people to independence, and his resolute leadership and bravery will never – nor should ever – be forgotten.

Yet his reputation is being tarnished by such allegiances to the old authoritarian patriarchal order that he once fought against as a young man. Culture is dynamic, and both internal and external progressive forces signal change in Timor-Leste.

Newer progressive forces in Timor contesting older hierarchies of power are in need of support and international solidarity, and supporters of Timor-Leste, and Gusmao in particular, in Australia and other places need to take note.

There are Timorese men working and advocating for an end to violence against women, alongside Timor’s tenacious women’s movement that has worked so hard in this space, but more political leadership on gendered violence is required by the state.

Timor Leste’s extremely youthful population represents a great opportunity for positive change and renewal.

Dr Sara Niner is a lecturer in anthropology, School of Social Sciences, Monash University. This article is republished from Lens Monash under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz