REVIEW: By David Robie

Four months ago, a group of lawyers in Aotearoa New Zealand called for a little reported inquiry into New Zealand spy agencies over whether there has been possible assistance for Israel’s war in Gaza.

In a letter to the chief of intelligence and security (IGIS) on 12 September 2024, three lawyers argued that the country was in danger of aiding international war crimes, reported RNZ News.

Inspector-General Brendan Horsley, who had previously indicated he would look into conflict-related spying this year, confirmed he would consider the request, according to the report.

- READ MORE: Behind settler colonial NZ’s paranoia about dissident ‘persons of interest’

- Other SIS security reports

At least one of the lawyers had been confident of a positive response, said the news report.

“I’m actually very optimistic,” noted University of Auckland associate professor Treasa Dunworth in the media interview about their argument that New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) and Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS) intelligence might be making its way to Israel via the US, “because our request is very, detailed, backed up with credible evidence, [and] is very careful.”

But she got a disappointing result. The following month, on October 9 — just seven weeks before the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Foreign Minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes and crimes against humanity — Inspector-General Horsley ruled out an inquiry at this time.

He said in a statement he did not want to “stop the clock” and tie up his office’s “modest resources to a deeper review of activity I have already been monitoring” while armed conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine were currently “active and dynamic”.

Rapid deterioration

Yet rapidly the 15-month Israeli war has deteriorated since then with President-elect Donald Trump due to take office in Israel’s main backer the United States later this month on January 20.

As the humanitarian situation in Gaza worsens with intensified attacks on hospitals and civilians, a breakdown of law and order at the border, and more than 50 complaints filed against Israel soldiers for war crimes in multiple countries, UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese has urged medical professionals worldwide to sever all ties with the pariah state.

I urge medical professionals worldwide to pursue the severance of all ties with Israel as a concrete way to forcefully denounce Israel’s full destruction of the Palestinian healthcare system in Gaza, a critical tool of its ongoing genocide.#FreeDrHussanAbuSafiya https://t.co/qzZ7CqufI6

— Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur oPt (@FranceskAlbs) December 30, 2024

Ironically, the New Zealand intelligence “debate” has coincided with the publication of a new book that has debunked the view that the SIS and GCSB have been working in the interests of New Zealand. The reality, argues social justice movement historian and activist Maire Leadbeater in The Enemy Within: The Human Cost of the State Surveillance in Aotearoa/New Zealand is that these agencies have been working in the interests of the so-called “Five Eyes” partners, including the United States.

Her essential argument in this robust and comprehensive 427-page book is that New Zealand’s state surveillance has been part of a structure of state control that “serves to undermine movements for social change and marginalise or punish those who challenge the established order. It had a deeply destructive impact on democracy.”

As she states, her primary focus is on the work of New Zealand’s main intelligence agencies, the SIS and the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) “and their forerunners, the political police”.

The author explains that she is not concerned with the “socially useful work of the contemporary police in the detection of criminal activity, including politically motivated crime”. She notes also that unlike the domestic spies, police detection work is subject to detailed warrants, there is due process over arrests, and the process is open to public scrutiny.

Leadbeater points out that while New Zealand experience with terrorism has been limited, neither of the country’s two main intelligence agencies were much help in investigating the three notorious examples — the unsolved 1984 Wellington Trades Hall bombing that killed one, the 1985 bombing of the Greenpeace environmental flagship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland that also killed one (but the casualties could easily have been higher), and the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings that murdered 51.

The regular police were the key investigators in all three cases.

Also, there is the failure of the SIS to discover Mossad agents operating in NZ on fake passports.

Working for ‘Five Eyes’ interests

Instead of working for the benefit of New Zealand, the intelligence agencies were set up to work closely with the country’s traditional allies and the so-called “Five Eyes” network — Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

An example of this was Algerian professor and parliamentarian Ahmed Zaoui who arrived in New Zealand in 2002 as an asylum seeker after a military coup against the elected government in his home country. Within nine days of arriving, his confidentiality was breached and he was falsely branded by The New Zealand Herald as an “international terrorism suspect”.

He was jailed for two years without charge (part of that time held in solitary confinement) because of an SIS-imposed National Security Risk certificate and this could have have led to “deportation of this honourable man” but for the tireless work of his lawyers and a well-informed public campaign, as told by Leadbeater in this book, and also by journalist Selwyn Manning in his 2004 book I Almost Forgot about the Moon: The Disinformation Campaign Against Ahmed Zaoui.

Set free and granted asylum, he later became a New Zealand citizen in 2014. (However, on a visit to Algeria in 2023 he was arrested at gunpoint in a house in Médéa and charged with “subversion”).

Leadbeater says a strong case could be made that New Zealand’s democracy “would be stronger and more viable without the repressive laws that currently support the secretive operations of the SIS and the GCSB”. The author laments that the resources and focus of the intelligence agencies have focused too much, and wastefully, on ordinary people who are perceived to be “dissenters”.

“Dissent is the lifeblood of democracy but SIS operations targeted many of our brightest and best, damaging their personal and professional lives in the process,” Leadbeater says.

Among those who have been targeted have been the author herself, and others in her “left-wing family milieu” — including her late brother longtime Green Party foreign affairs spokesperson Keith Locke, as well as her parents Elsie and Jack, originally Communist Party activists prior to 1956.

The core of the book is based on primary sources, including declassified police records held in the National Archives and the declassified records of the SIS which have been released to individual activists – including her and she discovered she had been spied on since the age of 10 due to state paranoia.

At the launch of her book in Auckland last November, guest speaker and retired First Union general secretary Robert Reid — whose file also features in the book — said what a fitting way the narrative begins by outlining the important role the Locke family have played in Aotearoa over the many years.

The final chapter is devoted to another “Person of interest: Keith Locke” – “Maire’s much-loved friend and comrade.”

“In between these pages is a treasure trove of commentary and stories of the development of the surveillance state in the settler colony of NZ and the impact that this has had on the lives of ordinary — no, extra-ordinary — people within this country,” Reid said.

“The book could almost be described as a political romp from the settler colonisation of New Zealand through the growth of the workers movement and socialist and communist ideology from the late 1800s until today.”

Surveillance stories and files

Among others whose surveillance stories and files have been featured are trade unionist and former Socialist Action League activist Mike Treen; Halt All Racist Tours founder Trevor Richards; economics lecturer Dr Wolfgang Rosenberg’s sons George and Bill; Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) organiser Murray Horton; antiwar activist and Peace Movement research Owen Wilkes; investigative journalist Nicky Hager; Dr Bill Sutch, who was tried and acquitted on a charge laid under the Official Secrets Act in 1975; and internet entrepreneur and political activist Kim Dotcom.

State paranoia in New Zealand was driven by issues of peace, anti-conscription, anti-nuclear, decolonisation, unemployed workers and left trade unionism and socialist and communist thought.

Leadbeater reflects that she had never accepted that “anyone in my family ever threatened state security. Moreover, the solidarity, antinuclear and anti-apartheid organisations that I took part in should not have been spied on. Such groups were and are a vital part of a healthy democracy.”

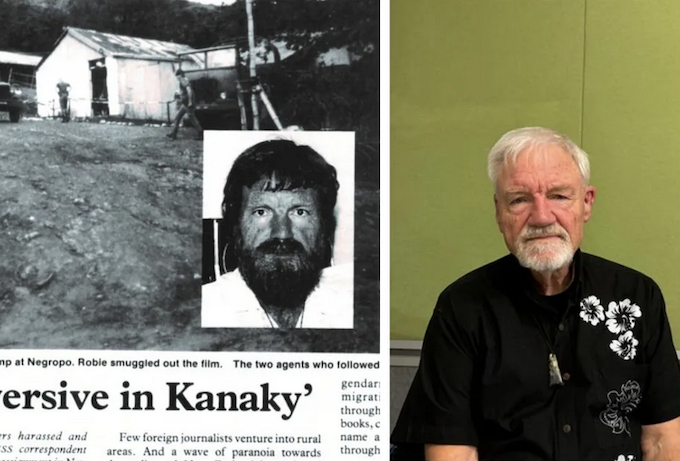

At one stage when many activists were seeking copies of their surveillance files in the mid-2000s through OIA requests or later under the Privacy Act, I also applied due to my association with several of the protagonists in this book and my involvement as a writer on decolonisation and environmental justice issues.

I merely received a “neither confirm or deny” form letter on the existence of a file, and never bothered to reapply later when information became more readily available.

But I have had my own brushes with surveillance and threatened arrest as a journalist in global settings such as New Caledonia, including when I was detained by soldiers in January 1987 for taking photographs of French military camps for a planned report about the systematic intimidation of pro-independence Kanak villagers.

This was perfectly legal, of course, and the attempt by authorities to silence me did not work; my articles appeared on the front page of the New Zealand Sunday Times the following weekend and featured on the cover of Fiji’s Islands Business news magazine.

Watched become the watchers

The structure of The Enemy Within is in three parts. As the author explains, the first part focuses on the period from 920 to the end of the First World War, and the second on the impact of the Cold War and the Western anti-communist hysteria between 1945 and 1955.

The final part covers the period from 1955 to the present, when the intelligence and security services have been under greater public scrutiny and faced campaigns for their reform or abolition.

As Leadbeater notes, “the watched, to some extent, have become the watchers”.

Because of my Asia-Pacific and decolonisation interests, I found a chapter on “colonial repression in Samoa” and the Black Saturday massacre of the Mau resistance of particular interest and a shameful stain on NZ history.

As Leadbeater notes, it was an “unexpected find in the Archives New Zealand” to stumble across a record of the surveillance of the “citizens who mounted an opposition to the New Zealand government’s colonial rule in Samoa”.

She pays tribute to the “vibrant solidarity movement” in the late 1920s and early 1930s, inspired by the peaceful Mau movement and its motto “Samoa mo Samoa” — Samoa for the Samoans — in their resistance to New Zealand’s colonial project.

This solidarity movement was in the face of a “prevailing attitude of white settlement” and its leaders were influenced by the Parihaka resistance of the 1880s.

Leadbeater is critical of New Zealand media, such as The New Zealand Herald, for siding with the colonial establishment and becoming “positively hostile to the Mau movement”.

New Zealand administrators under the League of Mandate to govern Samoa following German rule were arrogant and regarded Samoans as “inferior” and were “aghast” at Samoan and European leaders collaborating in resistance.

Black Saturday massacre

On 28 December 1929, what became dubbed the “Black Saturday massacre” happened in Apia. A peaceful Mau procession marches to the Apia wharf to welcome home exiled trader Alfred Smyth.

Police tried to arrest the Mau secretary, Mata’ūtia Karaunu, but the marchers protected him. More police were despatched to “assert colonial authority”, shots were fired at the crowd and in the upheaval a police constable was clubbed to death.

A police sergeant the fired a Lewis machine gun from the police station over the heads of the crowd, while other police fired directly into the crowd with their rifles.

Paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III, dressed in white and calling for peace, was mortally wounded and at least eight other marchers were also killed. The massacre was chronicled in journalist Michael Field’s books Mau and later Black Saturday: New Zealand’s Tragic Blunders in Samoa.

Protests followed and the Mau Movement was declared a “seditious organisation” and the wearing of Mau outfits or badges became illegal.

A crackdown ensued on Mau activists with heavy surveillance and harassment and in New Zealand public figures and community leaders called for an “independent inquiry into Samoan affairs”.

Eventually, the Labour Party victory in the 1935 elections changed the dynamic and the following year the Mau was recognised as a legitimate political movement.

After the Second World War, New Zealand became committed to self-government in Western Samoa with indigenous custom and tradition “as an important foundation”. However, full independence did not come until 1962.

Four decades later, in 2002, Prime Minister Helen Clark formally apologised to the people of Samoa for the “inept and incompetent early administration of Samoa by New Zealand”.

She cited officials allowing the “influenza” ship Talune to dock in Apia in 1918, and the Black Saturday massacre as key examples of this incompetence.

However, Leadbeater notes that the “saga of surveillance and sedition charges” outlined in her book could well be added to the list. She adds that Samoans remember the Mau Movement and its martyrs with “pride and gratitude”.

“For New Zealanders, this chapter in our colonial history is one of shame that should be far better known and understood. The New Zealand Samoa Defence League was ahead of its time, and thankfully so.”

Behind settler colonial #NZ’s paranoia about dissident ‘persons of interest’ | #AsiaPacificReport #MaireLeadbeater #progressivebooks #RobertReid @miketreen #statesurveillance #dissidents #statespying @JohnJohnminto https://t.co/B9qws9s1La pic.twitter.com/5ELHTIDv4l

— David Robie (@DavidRobie) November 9, 2024

Looking for ‘subversives’ in wrong places

Leadbeater notes in her book that the SIS budget alone in 2021 was about $100 million with about 400 staff. Yet the intelligence services have been spending this sport of money for more than a century looking for “subversives and terrorists” — but in the wrong places.

This book is an excellent tribute to the many activists and dissidents who have had their lives disrupted and hounded by state spies, and is essential reading for all those committed to transparent democracy.

Following her section on more contemporary events and massive surveillance failures and wrongs, such as the 2007 Tūhoe raids, Leadbeater calls for a massive rethink on New Zealand’s approach to security.

“It is time to leave crime, including terrorist crime, to the country’s police and court system, with their built-in accountability procedures,” she concludes.

“It is time for the state to stop spying on society’s critics.”

• The Enemy Within: The Human Cost of State Surveillance in Aotearoa/New Zealand, by Maire Leadbeater. Potton & Burton, 2024. 427 pages.