ANALYSIS: By David Robie, editor of Asia Pacific Report

Jean-Marie Tjibaou, a revered Kanak visionary, was inspirational to indigenous Pacific political activists across Oceania, just like Tongan anthropologist and writer Epeli Hao’ofa was to cultural advocates.

Tragically, he was assassinated in 1989 by an opponent within the independence movement during the so-called “les événements” in New Caledonia, the last time the “French” Pacific territory was engulfed in a political upheaval such as experienced this week.

His memory and legacy as poet, cultural icon and peaceful political agitator live on with the impressive Tjibaou Cultural Centre on the outskirts of the capital Nouméa as a benchmark for how far New Caledonia had progressed in the last 35 years.

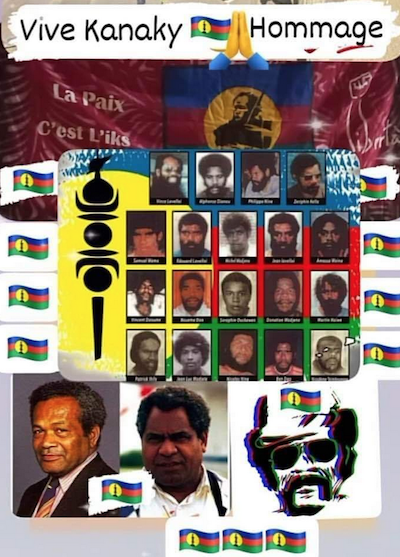

However, the wave of pro-independence protests that descended into urban rioting this week invoked more than Tjibaou’s memory. Many of the martyrs — such as schoolteacher turned security minister Elöi Machoro, murdered by French snipers during the upheaval of the 1980s — have been remembered and honoured for their exploits over the last few days with countless memes being shared on social media.

Among many memorable quotes by Tjibaou, this one comes to mind:

“White people consider that the Kanaks are part of the fauna, of the local fauna, of the primitive fauna. It’s a bit like rats, ants or mosquitoes,” he once said.

“Non-recognition and absence of cultural dialogue can only lead to suicide or revolt.”

And that is exactly what has come to pass this week in spite of all the warnings in recent years and months. A revolt.

Among the warnings were one by me in December 2021 after a failed third and “final” independence referendum. I wrote at the time about the French betrayal:

“After three decades of frustratingly slow progress but with a measure of quiet optimism over the decolonisation process unfolding under the Nouméa Accord, Kanaky New Caledonia is again poised on the edge of a precipice.”

As Paris once again reacts with a heavy-handed security crackdown, it appears to have not learned from history. It will never stifle the desire for independence by colonised peoples.

New Caledonia was annexed as a colony in 1853 and was a penal colony for convicts and political prisoners — mainly from Algeria — for much of the 19th century before gaining a degree of autonomy in 1946.

Here are my five takeaways from this week’s violence and mayhem:

1 Global failure of neocolonialism – Palestine, Kanaky and West Papua

Just as we have witnessed a massive outpouring of protest on global streets for justice, self-determination and freedom for the people of Palestine as they struggle for independence after 76 years of Israeli settler colonialism, and also Melanesian West Papuans fighting for 61 years against Indonesian settler colonialism, Kanak independence aspirations are back on the world stage.

Neocolonialism has failed. French President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to reverse the progress towards decolonisation over the past three decades has backfired in his face.

2 French deafness and loss of social capital

The predictions were already long there. Failure to listen to the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS) leadership and to be prepared to be patient and negotiate towards a consensus has meant much of the crosscultural goodwill that been developed in the wake of the Nouméa Accord of 1998 has disappeared in a puff of smoke from the protest fires of the capital.

The immediate problem lies in the way the French government has railroaded the indigenous Kanak people who make up 42 percent pf the 270,000 population into a constitutional bill that “unfreezes” the electoral roll pegging voters to those living in New Caledonia at the time of the 1998 Nouméa Accord. Under the draft bill all those living in the territory for the past 10 years could vote.

This would add some 25,000 extra French voters in local elections, which would further marginalise Kanaks at a time when they hold the territorial presidency and a majority in the Congress in spite of their demographic disadvantage.

Under the Nouméa Accord, there was provision for three referendums on independence in 2018, 2020 and 2021. The first two recorded narrow (and reducing) votes against independence, but the third was effectively boycotted by Kanaks because they had suffered so severely in the 2021 delta covid pandemic and needed a year to mourn culturally.

The FLNKS and the groups called for a further referendum but the Macron administration and a court refused.

3 Devastating economic and social loss

New Caledonia was already struggling economically with the nickel mining industry in crisis – the territory is the world’s third-largest producer. And now four days of rioting and protesting have left a trail of devastation in their wake.

At least five people have died in the rioting — three Kanaks, and two French police, apparently as a result of a barracks accident. A state of emergency was declared for at least 12 days.

But as economists and officials consider the dire consequences of the unrest, it will take many years to recover. According to Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCI) president David Guyenne, between 80 and 90 percent of the grocery distribution network in Nouméa had been “wiped out”. The chamber estimated damage at about 200 million euros (NZ$350 million).

4. A new generation of youth leadership

As we have seen with Generation Z in the forefront of stunning pro-Palestinian protests across more than 50 universities in the United States (and in many other countries as well, notably France, Ireland, Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom), and a youthful generation of journalists in Gaza bearing witness to Israeli atrocities, youth has played a critical role in the Kanaky insurrection.

Australian peace studies professor Dr Nicole George notes that “the highly visible wealth disparities” in the territory “fuel resentment and the profound racial inequalities that deprive Kanak youths of opportunity and contribute to their alienation”.

A feature is the “unpredictability” of the current crisis compared with the 1980s “les événements”.

“In the 1980s, violent campaigns were coordinated by Kanak leaders . . . They were organised. They were controlled.

“In contrast, today it is the youth taking the lead and using violence because they feel they have no other choice. There is no coordination. They are acting through frustration and because they feel they have ‘no other means’ to be recognised.”

According to another academic, Dr Évelyne Barthou, a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Pau, who researched Kanak youth in a field study last year: “Many young people see opportunities slipping away from them to people from mainland France.

“This is just one example of the neocolonial logic to which New Caledonia remains prone today.”

5. Policy rethink needed by Australia, New Zealand

Ironically, as the turbulence struck across New Caledonia this week, especially the white enclave of Nouméa, a whistlestop four-country New Zealand tour of Melanesia headed by Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters, who also has the foreign affairs portfolio, was underway.

The first casualty of this tour was the scheduled visit to New Caledonia and photo ops demonstrating the limited diversity of the political entourage showed how out of depth New Zealand’s Pacific diplomacy had become with the current rightwing coalition government at the helm.

Heading home, Peters thanked the people and governments of Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu and Tuvalu for “working with New Zealand towards a more secure, more prosperous and more resilient tomorrow”.

The delegation is now heading home ✈️

Many thanks to the people and governments of Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu & Tuvalu for their kind hospitality – and for working with New Zealand towards a more secure, more prosperous & more resilient tomorrow.

🇸🇧🇵🇬🇻🇺🇹🇻 🤝 🇳🇿 pic.twitter.com/ZciN70cNP6

— Winston Peters (@NewZealandMFA) May 16, 2024

His tweet came as New Caledonian officials and politicians were coming to terms with at least five deaths and the sheer scale of devastation in the capital which will rock New Caledonia for years to come.

News media in both Australia and New Zealand hardly covered themselves in glory either, with the commercial media either treating the crisis through the prism of threats to tourists and a superficial brush over the issues. Only the public media did a creditable job, New Zealand’s RNZ Pacific and Australia’s ABC Pacific and SBS.

In the case of New Zealand’s largest daily newspaper, The New Zealand Herald, it barely noticed the crisis. On Wednesday, morning there was not a word in the paper.

Thursday was not much better, with an “afterthought” report provided by a partnership with RNZ. As I reported it:

“Aotearoa New Zealand’s largest newspaper, the New Zealand Herald, finally catches up with the Pacific’s biggest news story after three days of crisis — the independence insurrection in #KanakyNewCaledonia.

“But unlike global news services such as Al Jazeera, which have featured it as headline news, the Herald tucked it at the bottom of page 2. Even then it wasn’t its own story, it was relying on a partnership report from RNZ.”

New Zealand Herald finally catches up with the Pacific’s biggest news story after 3 days of crisis #CafePacific #kanaky #newcaledonia #nzherald #media #insurrection #stateofemergency #franceinpacific @KanakySuport @cpcflnkspt @westpapuamedia @anaisduongp https://t.co/TZZ2JDE6nr pic.twitter.com/52bJDECU2g

— David Robie (@DavidRobie) May 16, 2024

Also, New Zealand media reports largely focused too heavily on the “frustrations and fears” of more than 200 tourists and residents said to be in the territory this week, and provided very slim coverage of the core issues of the upheaval.

With all the warning signs in the Pacific over recent years — a series of riots in New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tonga and Vanuatu — Australia and New Zealand need to wake up to the yawning gap in social indicators between the affluent and the impoverished, and the worsening climate crisis.

These are the real issues of the Pacific, not some fantasy about AUKUS and a perceived China threat in an unconvincing arena called “Indo-Pacific”.

Dr David Robie covered “Les Événements” in New Caledonia in the 1980s and penned the book Blood on their Banner about the turmoil. He also covered the 2018 independence referendum.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz