Opinion by Lynley Hood.

Forty years on from my 1985 Fulbright Grant, my disquiet over the war in Gaza evoked some troubling questions.

The answer to my first question – What is the primary purpose of the Fulbright Programme? – was on the Fulbright NZ website. It says:

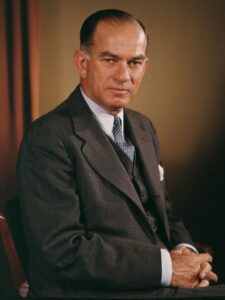

The Fulbright programme was established in 1946 as an initiative of US Senator J. William Fulbright, to promote mutual understanding through educational and cultural exchanges between the US and other countries. Informed by his own exchange experience as a Rhodes Scholar, Senator Fulbright believed the programme could play an important role in building a lasting world peace in the aftermath of World War II.

The Fulbright Programme has been described as one of the largest and most significant movements of scholars across the face of the earth and now operates in over 155 countries, funding around 8,000 exchanges per year for participants to study, research, teach or present their work in another country.

In Senator Fulbright’s words, the programme aims “to bring a little more knowledge, a little more reason, and a little more compassion into world affairs and thereby to increase the chance that nations will learn at last to live in peace and friendship.” This goal has always been as important to the programme as individual scholarship. (ref. https://fulbright.org.nz/ )

My next question was: If Senator Fulbright really did say that, why isn’t the international Fulbright community in an uproar over the anti-Palestinian war-mongering being pursued by the USA, Israel, Germany and the UK? They’re all Fulbright countries, but instead of working for peace they’re faciliating genocide by supplying arms and ammunition for the war in Gaza.

After finding no answer to that question, my inner protester told me to speak out, and my inner editor told me to check my sources first. So after scrolling through scores of unsourced quotes, I took my search for reliable sources to Dunedin second hand bookshops – and found a treasure.

The Arrogance of Power by J. William Fulbright, Chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was published by Jonathan Cape in 1967. Here are some quotes:

Having done so much and succeeded so well, America is now at that historical point at which a great nation is in danger of losing its perspective on what exactly is within the realm of its power and what is beyond it. Other great nations, reaching this critical juncture, have aspired to too much, and by overextention of effort have declined and then fallen.

The causes of the malady are not entirely clear but its recurrence is one of the uniformities of history: power tends to confuse itself with virtue and a great nation is peculiarly susceptible to the idea that it’s power is a sign of God’s favour, conferring upon it a special responsibility for other nations — to make them richer and happier and wiser, to remake them, that is, in its own shining image. Power confuses itself with virtue and tends also to take itself for omnipotence. Once imbued with the idea of a mission, a great nation easily assumes that it has the means as well as the duty to do God’s work. The Lord, after all, surely would not choose you as His agent and then deny you the sword with which to work His will. German soldiers in the First World War wore belt buckles imprinted with the words “Gutt mit uns [God is with us].” It was approximately under this kind of infatuation — an exaggerated sense of power and an imaginary sense of mission — that the Athenians attacked Syracuse and Napoleon and then Hitler invaded Russia. In plain words, they overextended their commitments and they came to grief.

The stakes are high indeed: they include not only America’s continued greatness but nothing less than the survival of the human race in an era when, for the first in history, a living generation has the power of veto over the survival of the next.

When the abstractions and subtleties of political science have been exhausted, there remains the most basic unanswered questions about war and peace and why nations contest the issues they contest and why they even care about them. As Aldous Huxley has written:

There may be arguments about the best way of raising wheat in a cold climate or of reafforesting a denuded mountain. But such arguments never lead to organised slaught. Organised slaughter is the result of arguments about such questions as the following: Which is the best nation? The best religion? The best political theory? The best form of government? Why are other people so stupid and wicked? Why can’t they see how good and intelligent we are? Why do they resist our beneficent efforts to bring them under our control and make them like ourselves?

Many of the wars fought by man — I am tempted to say most — have been fought over such abstraction. The more I puzzle over the great wars of history, the more I am inclined to the view that the causes attributed to them — territory, markets, resources, the defence or perpetuation of great principles — were not the root cause at all but rather explanations or excuses for certain unfathomable drives of human nature. For lack of a clear and precise understanding of exactly what these motives are, I refer to them as the “arrogance of power”— as a psychological need that nations seem to have in order to prove that they are bigger, better, or stronger than other nations. Implicit in this drive is the assumption, even on the part of normally peaceful nations, that force is the ultimate proof of superiority — that when a nation shows that it has the stronger army, it is also proving that is has better people, better institutions, better priciples, and in general, a better civilisation.

Evidence for my proposition is found in the remarkable discrepancy between apparent and hidden causes of some modern wars…

The United States went to war in 1898 for the stated purpose of liberating Cuba from Spanish tyranny, but after winning the war — a war which Spain had been willing to pay a high price to avoid — the United States brought the liberated Cubans under an American protectorate and incidentally annexed the Philippines, because, according to President McKinley, the Lord told him it was America’s duty “to educate the Filipinos and uplift and civilize and Cristianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as fellowmen for who Christ also died.”

Isn’t it interesting that the voice was the voice of the Lord but the words were those of Theordore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Admiral Mahan, those “imperialists of 1898” who wanted America to have an empire just because a big powerful country like America ought to have an empire? The spirit of the times was expressed by Albert Beveridge, soon thereafter elected to the United States Senate, who proclaimed Americans to be “a conquering race;” “We must obey our blood and occupy new markets and if necessary new lands,” he said, because “In the Almighty’s infinite plan . . . debased civilisations and decaying races” must disappear “before the higher civilisations of the nobler and more virile type of man.”