Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Lynda Goldsworthy, Research Associate, University of Tasmania

Amid the challenges of climate change, resource extraction and pollution, the survival of species and ecosystems depends on setting aside protected areas. But plans to establish marine protected areas in East Antarctica have stalled.

Next week, the 27-member Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources will gather at a special meeting in Santiago, Chile, to try to break the deadlock. There’s much at stake, given the seemingly implacable opposition from China and Russia. China appears more concerned about fishing for krill than conservation, while Russia’s objections are less clear.

The need for Antarctic marine protected areas was first discussed in response to the 2002 United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development. The formal plan was adopted three years later, in 2005. While China had not yet joined the commission at that time, it was a member when the commission reaffirmed this commitment in 2011.

These areas were meant to protect a representative suite of Antarctic marine environments, such as unique seafloor communities, deepwater canyons, and highly productive coastal and oceanic food webs. They were to be developed, assessed and agreed on the basis of the best available science.

Slow progress on Antarctica’s marine parks

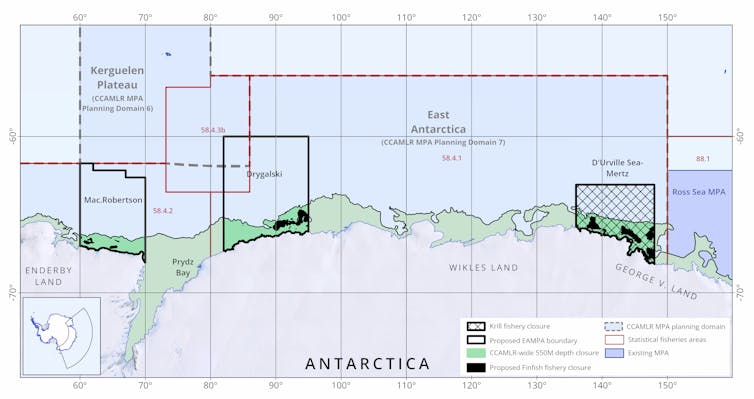

So far, two marine protected areas have been agreed by the commission: South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf in 2009; and the Ross Sea Region in 2016. Since then, the commission has been unable to agree on any further proposals, including the East Antarctic Region marine protected area. This was first proposed by Australia in 2011. It’s the oldest of those proposed but not yet agreed. The commission has also been unable to adopt the research and monitoring plans or the reviews of the existing marine protected areas.

CEMARC, Author provided

This year, the United Nations agreed to a treaty on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. This treaty will be up for adoption at a final conference session on June 19-20, 2023.

This treaty sets a global target of 30% of the global oceans to be in marine protected areas by 2030. This will be the likely yardstick against which the Commission’s future performance will be measured. So far, the commission’s marine protected area achievement is just 4.7% of the area of Southern Ocean that it is responsible for.

Of the 27 member countries of the commission, 21 have formally committed their support for the East Antarctic Region marine protected area. Only China and Russia have repeatedly opposed this and other proposals. They are now challenging the commission’s consensus agreement to establish the marine protected area network in Antarctica.

The shrinking East Antarctic Region Marine Protected Area

The proposed East Antarctic Region marine protected area initially consisted of seven distinct areas designed to protect the diversity of environments in the region. Since then, Australia and its partners, now numbering 17, have granted many compromises in the quest for consensus. The number of distinct areas has been reduced to three and fishing is allowed unless explicitly excluded.

To specifically accommodate China’s concerns about future krill fishing, Australia sacrificed the unique and special Prydz Bay region. That’s despite the fact China’s krill fishing aspirations could be more than adequately met from the rest of the region. Nonetheless, Russia and China continue to withhold consensus on this proposal.

Increasingly, the rhetoric opposing marine protected areas is centred around an argument that invokes a “balance” between “conservation” (in this case, the establishment of marine protected areas), and “rational use” (in this case the right to fish). On both legal and practical grounds, the conservation versus rational use argument centres on the very core of the international agreement that covers the oceans of the region, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

The convention was agreed in 1980 to protect all Antarctic species from potential over exploitation. Its objective was – and remains – clearly centred on conservation in the region. Fishing is allowed, as long as the species and ecosystems of the region are conserved. The convention states that its objective “is the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources”. It identifies those resources as “populations of fin fish, molluscs, crustaceans and all other species of living organisms, including birds” and clarifies that “conservation” includes “rational use”, if such rational use can be conducted with minimal impact on the ecosystem.

In recent years, Russia and China have both argued that there is too much emphasis on conservation. They state that there needs to be a re-balancing between fishing and conservation. In constructing this argument, they are engaging in a wilful reinterpretation of the convention – and ignoring the significant time dedicated by the commission to fisheries management.

A reliance on consensus

The commission, like the rest of the Antarctic Treaty System, makes decisions on the basis of consensus. This means that some decisions take may take quite some time to be agreed, but the strength of consensus is that all parties are then committed to the final result.

Consensus is built on trust and good faith. But consensus will be undermined when agreement is withheld in bad faith, or used as a means to achieve other objectives. The actions of one or a few that withhold consensus, or who negotiate in bad faith, could, if not confronted, undermine all decision-making in the commission, including decisions on sustainable fisheries.

Now is not the time for endless compromise

We must not continue compromising for an apparent “quick win”. The East Antarctic Region marine protected area has been evaluated by the commission’s scientific committee, and the commission has repeatedly reached the point where only Russia and China withhold agreement. It is this behaviour that needs to be explicitly challenged, not the marine protected area proposal itself.

These nations need to explain their specific concerns, and in the spirit of consensus, provide workable alternatives that meet their obligations under the conventions and accommodate the aspirations of all members.

Australia has held many discussions with China and Russia over the years to help resolve their issues. With China, these discussions have been thorough and cordial, and it is clear this nation has a deep and comprehensive understanding of the marine protected area proposal. Several bilateral meetings have also been held with Russia; however, it remains unclear what their specific objections are, particularly as they are no longer fishing.

There are no obstacles to China agreeing to the East Antarctic Region marine protected area proposal now. They have agreed to two large Antarctic marine protected areas in the past. The East Antarctic marine protected area poses no substantive obstacle to China’s aspirations in the region, including their stated desire to harvest krill.

There is much at stake at this upcoming special meeting, including the reputation of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. The protection of the Antarctic requires that a way forward on marine protected areas be found.

Read more:

Australia wants to install military technology in Antarctica – here’s why that’s allowed

![]()

Marcus Haward receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre.

Lynda Goldsworthy and Tony Press do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Can next week’s special meeting in Chile break the deadlock over East Antarctica’s marine park proposal? – https://theconversation.com/can-next-weeks-special-meeting-in-chile-break-the-deadlock-over-east-antarcticas-marine-park-proposal-206531