Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Leigh Carriage, Senior Lecturer in Music, Southern Cross University

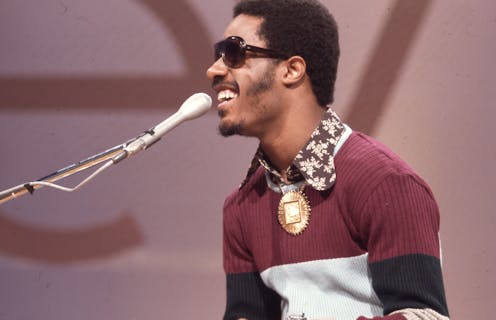

On October 24 1972, Stevie Wonder released his 15th album Talking Book and the world heard the infectious grooves and seamless vocal delivery of the song Superstition for the very first time.

Superstition reached number one in the Billboard Hot 100 and on the soul singles chart.

The song has been covered by an astounding number of artists, from Mel Torme to Stevie Ray Vaughan and Macy Gray, French musician Tété and a unique mashup from Pomplamoose.

Superstition is frequently played at gigs and gatherings all over the globe because the bass riff and driving drum groove have so much dance appeal – a mix of the unexpected syncopation and repetition of the chorus hook. The song feels alive.

A simple structure

The listener can’t help but respond directly to the infectious opening groove played by Wonder.

Three key instruments forge the captivating and carefully arranged funk groove in the introduction: the Hohner Clavinet (an electronic harpsichord – more on this later), drums and the Moog bass. The cohesion is musical magic.

Superstition’s recording engineer Malcolm Cecil recalled

how Wonder recorded the entire song on drums first, with no reference other than the song in his head, then the keyboard bass part, and then the Clavinet.

This illustrates how complete his conceptualisation of the song was prior to recording.

The song’s structure is simple. The introduction sets up the familiar groove with its static harmony, pulsing bass and keyboard riff.

The verse proceeds over the same static harmony, with a new bass riff introduced halfway through, effecting a shift to a higher dynamic level.

The chorus releases the tension with a sophisticated cadence, reflecting jazz sensibilities and revealing the breadth of Wonder’s musical knowledge.

This structure is repeated, followed by an instrumental version of the chorus. Then there’s a final verse and chorus before a long instrumental section built on the verse riff leads to the final fade out.

Read more:

Groovy findings: Researching how and why music moves you

Unexpected instruments

One of the most memorable parts of the song is the signature played on the Hohner Clavinet.

A Clavinet looks like an electric keyboard, but it is an electro-mechanical string instrument originally developed for the performance of classical harpsichord and clavichord music.

Like the Hammond organ of the 1930s, it was soon discovered and adopted by many contemporary musicians.

Wonder had already used the instrument on I Was Made to Love Her (1967), Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day (1968) and I Don’t Know Why (1969). According to music journalist Martin Horn, Wonder wanted to use the Clavinet on Superstition to “full effect” to “show off”. Wonder had described the instrument as “funky, dirty, stinky”.

In some ways, the Clavinet is doing the job a guitarist might normally do. It plays the single note riff at the core of Wonder’s song, and chord parts similar to what you would hear from a strummed guitar. But there are also several other barely audible tracks of clavinet, which subtly add to the texture.

Superstition’s bass line is played on an analog synthesiser called TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra). This is an extraordinary collection of electronics which filled an entire room, adding to the song with a totally unique sonic palette – akin to a PVC pipe hit with a thong.

Standing the test of time

The contributions from the horn parts are also integral, played by Steve Madaio on trumpet and Trevor Lawrence on the tenor saxophone.

The horns first appear playing in unison with the bass line in the second half of the verse, emphasising the lift in energy. They play long notes in the chorus emphasising the melody, then reinforce the rhythmic figure at the crest of resolution.

Their part culminates in a powerful instrumental hook answering the vocal hook, “superstition ain’t the way”. These parts are repeated in the ensuing verses and choruses.

After the final chorus the horns cycle through a sequence containing the verse riff, the chorus hook and a short passage of long notes adapted from the chorus melody.

The melody of Superstition is very singable. Wonder’s delivery is fluid and highly expressive. He sings relatively short phrases, allowing the keyboard riffs to fill the space at the end of each phrase.

It isn’t until the chorus that Wonder delivers the first effortless vocal lick on “suffer”. His vocal delivery remains understated, with occasional punctuated phrases, gravel tones and a scream within the horn part.

The song ends with a long 50 second fade out, reinforcing the riff.

Superstition and Wonder’s vocal delivery is so dependable, groovy and secure musically. The listener feels free to give themselves over fully, to trust Wonder completely and lose themselves for a moment.

Superstition stands the test of time.

Read more:

Why we’re obsessed with music from our youth

![]()

Leigh Carriage does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Dissecting Stevie Wonder’s Superstition, 50 years after we first heard its infectious grooves – https://theconversation.com/dissecting-stevie-wonders-superstition-50-years-after-we-first-heard-its-infectious-grooves-189551