Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Thomas Longden, Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The federal government’s climate change bill passed the Senate on Thursday. Among the mandates in the new Climate Change Act are assessments of the social, employment and economic benefits of climate change policies.

These assessments will be included in annual statements, prepared by the government with input from the Climate Change Authority.

A letter we published today in The Lancet Planetary Health outlines the importance of measuring the effects of climate change on human health when assessing the social cost of carbon.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions will improve the health of Australians, especially by reducing air pollution from electricity generation and road transport. Every year, around 2,600 (2% of) Australian deaths are attributed to air pollution from human activities such as transport, mining, and power generation using fossil fuels.

And as the planet continues to warm, heatwaves, bushfires and floods will bring a heavier social impact. For example, natural hazards are responsible for an estimated 30% of total insurance costs today. Australian home insurance premiums would increase by as much as 15% (A$782 million) by 2050 if global emissions continue unabated.So let’s explore what the social cost of carbon entails, and why it should inform policymaking in Australia in areas such as fossil fuel extraction, infrastructure projects and emissions reduction.

Read more:

What is the ‘social cost of carbon’? 2 energy experts explain

What is the social cost of carbon?

The social cost of carbon is a monetary value of the harms of climate change associated with emitting an additional tonne of carbon dioxide.

Estimating this cost should capture harms to human health, decreased agricultural productivity, damages from natural disasters and other effects on the economy.

A study this month in Nature put the global social cost of carbon at A$275 per tonne of CO₂ released. Impacts on health (49%) and agriculture (45%) accounted for most of this.

Shutterstock

Climate change poses grave risks to many Australian homes, lives and livelihoods through, for example, worsening floods, heatwaves and bushfires.

Australia’s new climate change law legislates emissions reduction of 43% below 2005 levels by 2030, and reaching net-zero by 2050. It also requires climate policy benefits to be assessed each year.

But we don’t know exactly how the assessments will be conducted, and the law does not explicitly mention measuring the social cost of carbon.

Weighing up the social cost of projects

Accounting for the social cost of carbon would lead to investment and policy decisions that support emissions reduction. It would also deter support for projects that increase emissions, such as new coal mines.

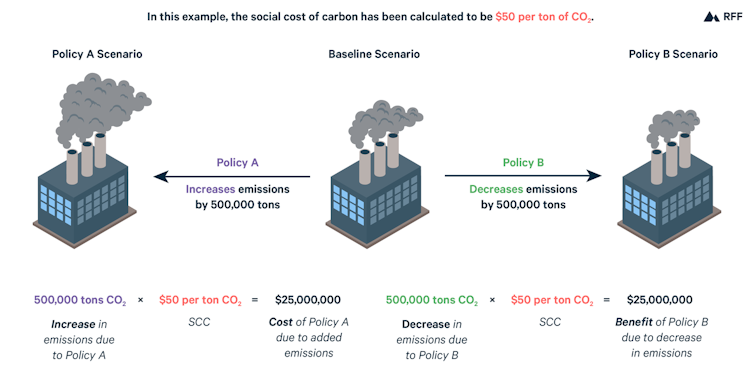

Decision-makers often use a cost-benefit analysis to assess and compare projects. If a project increases emissions, the social cost of carbon multiplied by the expected emissions should be added to the overall costs of the project.

Projects that decrease emissions, such as a new offshore wind farm, should have these benefits included in the assessment, bringing the overall net cost of the project down. Infrastructure Australia’s guide to economic appraisal mentions such an approach.

RFF

The United States and Canada already include the social cost of carbon in assessments of federal regulatory proposals and investments. 14 US states, including California and New York, also use the measure.

Last year, the Biden administration announced it would increase the social cost of carbon to A$76 per tonne of CO₂, which is much higher than the A$10 per tonne of CO₂ used by the Trump administration.

Also in 2021, the Australian Capital Territory became the first and only Australian jurisdiction to adopt the social cost of carbon. It was set at an interim A$20 per tonne of CO₂ and will be reviewed in future.

What we’re calling for

A key component of calculating the social cost of carbon is a damage function that typically uses a single equation to estimate a global GDP loss.

However, as we argue in our letter, regional and sub-national damage functions would better capture the diverse range of climate change impacts, especially for human health and agriculture.

For example, losses in agricultural and labour productivity from heat stress differ by country. Economic losses range from less than 2% per year to over 28% per year in 2100, depending on the country and emissions scenario used.

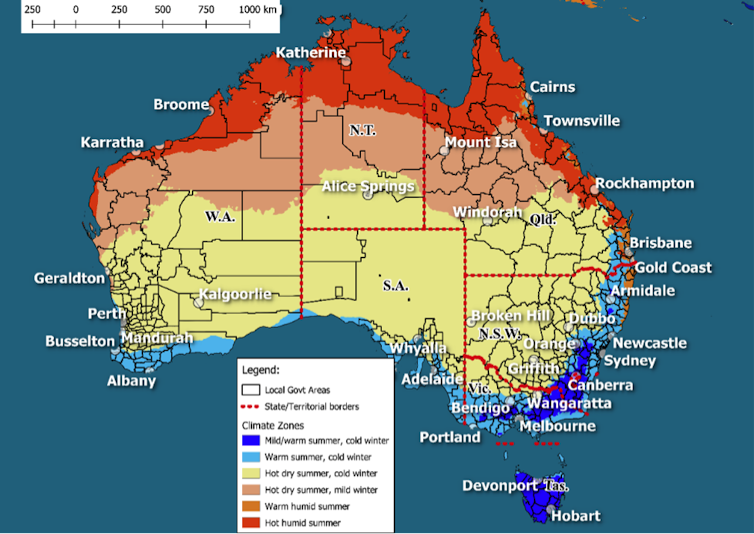

Also, climate zones are a key determinate of the number of deaths associated with extremely hot and cold temperatures.

Read more:

Heat kills. We need consistency in the way we measure these deaths

Our arguments are echoed by a US Interagency Working Group on the social cost of carbon. In 2017, it recommended separating market and non-market climate damages by region and sector.

Australia’s new annual climate change statement should also explicitly examine the health benefits of climate policies. These are likely to include fewer respiratory illnesses as a result of cleaner air, and increases in exercise associated with active travel options such as walking and cycling.

Understanding these health benefits will also improve decision-making and could change our approach to dealing with climate change.

Longden (2019)

Better climate decision-making

Climate change and related extreme events are already being felt in Australia. Back-to-back floods this year and the devastating Black Summer bushfires are just a few examples of our vulnerability to extreme weather events.

Governments must account for the impacts of these events when making decisions. Annual assessments of climate change policies are a decent start. Establishing a robust method to explicitly measure the social cost of carbon would go one better.

Read more:

222 scientists say cascading crises are the biggest threat to the well-being of future generations

![]()

Thomas Longden receives funding from the Healthy Environments And Lives (HEAL) National Research Network as part of the National Health and Medical Research Council special initiative in Human Health and Environmental Change (grant number 2008937).

He also receives funding from the Australian Government Department of Defence.

He is a member of the ACT Climate Change Council, which provides advice to the Minister for Water, Energy and Emissions Reduction on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change.

Richard Norman receives funding from the NHMRC through the HEAL Network

Sotiris Vardoulakis is the Director of the Healthy Environments And Lives (HEAL) Network, which receives funding from the NHMRC Special Initiative in Human Health and Environmental Change. He also receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the NSW Government, CSIRO, Asthma Australia, and Dyson. He is a member of the Public Health Association of Australia and of the Climate and Health Alliance.

Tom Kompas receives funding from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planing.

– ref. Australia finally has new climate laws. Now, let’s properly consider the astounding social cost of carbon – https://theconversation.com/australia-finally-has-new-climate-laws-now-lets-properly-consider-the-astounding-social-cost-of-carbon-190050