Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Shino Konishi, Associate professor, Australian Catholic University

Prior to colonisation there were approximately 250 different Aboriginal languages spoken by some 500 clans throughout Australia. Each clan possessed numerous Dreaming stories, depicting how the land was traversed and marked by the Ancestral Beings, who created land-forms, people, animals, plants and celestial stars.

Their experiences, and often the consequences of their actions, formed the basis for Aboriginal kinship systems, laws, ways of caring for Country and connecting to land.

These ancestors are not relegated to the past, for their presence is still felt at sacred sites, and they are still responsible for providing the resources that sustain the clan. Some Aboriginal people maintain their connection to these powerful beings by continuing to perform the songs and dances they gave them, and marking their bodies and objects with their sacred designs.

Thus Aboriginal cultures are necessarily rich with symbolism. Towards the end of the 20th century, Aboriginal culture was increasingly being called upon to provide a symbol of nation – representing Australia as a whole – by groups of non-Indigenous Australians who believed it offered a depth and richness of symbolic meaning that more conventional symbols had lost (or perhaps had never had).

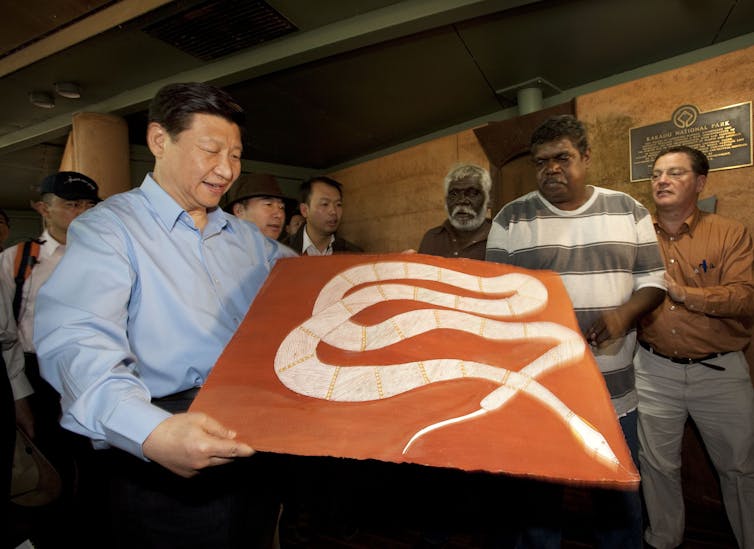

The most widely known Ancestral Being is the Rainbow Serpent, or Rainbow Snake, the English names for the figure that appears in the Dreamings of many different Aboriginal language groups across the continent.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

It features as an important creator figure, guardian of sacred places, bringer of monsoonal rains and storms, bestower of powers upon healers and rainmakers, or a dangerous creature that punishes people who violate laws, or dwells in waterholes threatening to swallow unwary passers-by, to name just a few incarnations.

It is also strongly connected with fertility, both human and ecological. In all

of its guises and geographies the Rainbow Serpent is associated with

water, an essential resource, and the rainbow, whose shimmering light

and curved form reflects the scales and body of the snake. The rainbow

is also an important bridge between the water and the sky, the sky yet

another resting place for the Rainbow Serpent.

shutterstock

Just one of the many Rainbow Serpents who travelled the land

is Yingarna, whose story is told by Kunwinjku-speaking people from

western Arnhem Land. In one of many stories she was said to be the first Rainbow Serpent, and all of creation burst from her body. The Kunwinjku also possess Dreaming stories about Yingarna’s child, Ngalyod, who is associated with the “potentially destructive power of the storms and the plenty of the wet seasons”.

The immense power that Yingarna and Ngalyod have is both creative and destructive: these Rainbow Serpents are not simply benevolent symbols of unity, but can also be threatening, so their resting places should be avoided. This menacing aspect has been symbolised in Dick Nguleingulei Murrumurru’s painting from the National Museum of Australia’s collection, which depicts Yingarna with

terrible crocodile’s teeth and tail, and a round, emu-like body capable of holding all she has swallowed.

The idea of the Rainbow Serpent as a composite of many other animals and even plants appeared elsewhere; western Arnhem Land rock paintings portray Rainbow Serpents with the head of a kangaroo, body of a snake, tail of a barramundi, and yam-shaped protrusions from the body. The oldest of these rock paintings have been dated to 6000 years, supporting the argument that Rainbow Serpent stories are among the world’s oldest continuous religious traditions.

This makes it especially useful as a national symbol, claiming

for modern Australia both universality and longevity.

Read more:

‘Dreamtime’ and ‘The Dreaming’: who dreamed up these terms?

For Aboriginal people the Rainbow Serpent is not relegated to the past and time of creation, but remains an awesome source of power that shapes the contemporary world. When Cyclone Tracy devastated the city of Darwin in 1974, local Aboriginal people interpreted it as a “warning to stop neglecting their traditional law and associated rituals”, and succumbing to the temptations of “lawless” city

life.

Attaching meaning

Non-Indigenous Australians have known stories about other Rainbow

Serpents since colonial times. Francis Armstrong, the first government

interpreter of the Swan River Colony (now Perth), recorded an account

of the Waugal (also spelled Wagyl), a Noongar Rainbow Serpent, in 1836,

seven years after the establishment of the settlement. He observed that

there were

certain large round stones, in different parts of the Colony,

which they [Noongar people] believe to be the eggs laid by the waugal … On passing such stones, they are in the habit of making a bed for it, of

the rushes of the blackboy [balga, grass tree or Xanthorrhoea preissii].

This was because, according to Noongar elder Clarrie Isaacs, the Waugal

had created the Swan River and all its associated waterholes, and “has the

power of life and death over Aborigines and demands the respect due to

it”.

However, despite noticing the reverence that the Noongar paid these

stones, the settlers still removed them from their place, indicating that

they accorded them no significance.

This instance suggests the difficulty

of translating the symbolic significance of an object and story across

cultures, especially when there is such disparity in power relations. But

in addition it reveals the way the very land contained symbolic meaning

for Indigenous people, whereas for the increasingly utilitarian colonisers

the land was reduced to little more than an economic resource.

The Rainbow Serpent, then, means different things for Indigenous

and non-Indigenous Australians. Armstrong’s example demonstrates

that in the early period it was considered a mere curiosity and

disregarded, for the colonists were busy transforming and re-purposing

the land.

Conflicting attitudes about the Waugal arose again in the 1980s when the state government wanted to redevelop the site of the Old Swan Brewery, also known as Goonininup, a resting place of the Rainbow Serpent.

Harry and Rowena Kennedy/flickr, CC BY-NC

Again, a century and a half later, few non-Indigenous Western Australians sympathised with Noongar protests, and received the idea of the Waugal with great scepticism. Isaacs attempted to find equivalences in European systems of belief:

They say because when they drive past the site that because they

cannot see some sort of ridiculous fire breathing dragon-like creature

poking its Loch Ness Monster-like head from the waters that it does

not exist. It is as ridiculous as myself making an assertion that God

is actually a large white man sitting on a throne atop some puffy

clouds.

But the developers ignored inconvenient arguments about religious

symbolism, preferring a more self-interestedly rational interpretation

which, according to cultural studies scholar John Fielder, demonstrates the imperial nature

of Western rationality, where our logic renders all other logics as

essentially illogical, irrational – not to be thought of as logic at all.

The Noongar saw the Waugal as a “spiritual being”, while their opponents

saw the Waugal as “some wildly primitive superstition” and the Noongar

themselves as troublemakers.

‘Domesticated’

However, non-Indigenous Australians have attached a range of

other meanings to the Rainbow Serpent, for the most part far from

hostile. This is partly due to the influence of anthropologists who, in the

early 20th century, became interested in what they called “myth”.

Anthropologist AR Radcliffe-Brown compiled a survey of stories from different Aboriginal language groups across Australia, and concluded

that the Rainbow Serpent occupied “the position of a deity”. Despite

noticing many differences in these stories, Radcliffe-Brown assumed that there was just a single Rainbow Serpent, and that it was akin to a god, “the most important nature-deity”. It was a view that greatly influenced non-Indigenous Australian understandings.

Taken out of the particular contexts of each language group’s

Dreamings, the Rainbow Serpent has been stripped of its numerous

ambivalent symbolisms and iconographic forms, and frequently

reduced to a singular entity – a benevolent mother/creator-figure in

the form of a brightly coloured snake.

Read more:

Indigenous cultural appropriation: what not to do

Perhaps this is in part due to the snake’s particular morphology; it is easy to imagine its enormous sinuous body carving out the rivers and creeks in the ancient “Dreamtime” (as it used to be described), whereas the meaning of the multiple symbolisms and composite form of Yingarna, Ngalyod and other Rainbow Serpents discussed by Aboriginal clans eludes outsiders.

It could be argued that this new rendering as a benevolent snake is a process of intellectual colonisation, for the settlers have domesticated the Rainbow Serpent, making it comprehensible and palatable to Western ideas. It was a case of non-Indigenous Australia connecting to Aboriginality only on a disembodied and superficial aesthetic level rather than at a level of deep understanding.

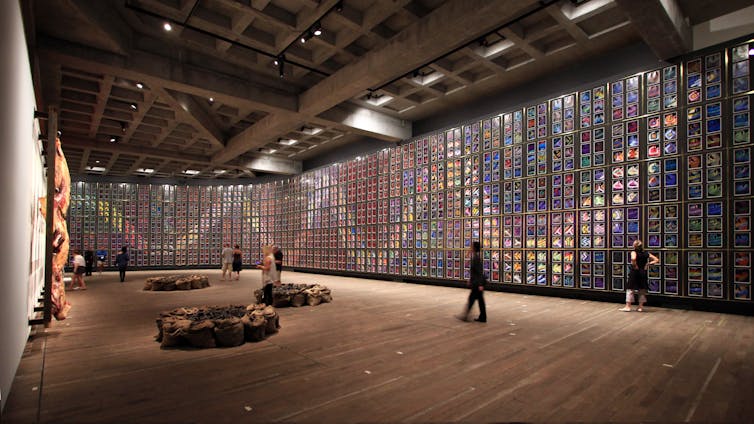

In the 1970s, celebrated Australian artist Sidney Nolan painted two large

murals depicting Rainbow Serpents. Snake, a 45-metre long mosaic was said to be Nolan’s “homage to Australia’s Aborigines”.

Wikimedia Commons

The second work, Little Snake was inspired by the sight of the Central Australian desert blooming after years of drought. Nolan used the Rainbow Serpent to represent “the magical power of water that brings

life from a state of stasis”.

It is this “domesticated” image of the giant brightly coloured snake with which Australians are probably most familiar, and which would prove most suitable for representing the Australian nation as a whole.

A commonplace symbol

Since then, images of Rainbow Serpents have slithered across school walls and community murals in suburbs and towns throughout the nation, at least those with large Indigenous or left-leaning populations.

The education system has taken the Rainbow Serpent to its widest audience. For many young Australians the Rainbow Serpent has been packaged as an Indigenous fairytale. From the 1970s, Australian children have read illustrated books depicting the life and adventures of the Rainbow Serpent.

goodreads

By the 1990s, children could paint their own Rainbow Serpent designs during NAIDOC Week, Harmony Day, or other events celebrating Australia’s multiculturalism. For adult Australians, the Rainbow Serpent has a number of other connotations. Tourists have been able to buy prints, T-shirts, books and jewellery or even underpants decorated with the great snake’s sinuous form, as an exotic souvenir of Australia.

Walkers and leisure-seekers can photograph, sit on or picnic by large public sculptures of the snake in public spaces, where it was intended to acknowledge and commemorate Aboriginal people. And since 1997 New Agers, ravers and ecotourists can come from “across the globe to dance a common dream” at the annual Rainbow Serpent Festival in Lexton, central Victoria, to camp and dance, but also learn from local Dja Dja Wurrung and Wadawurrung peoples and other Indigenous people from the Pacific and north America.

The New Age market has been one of the most avid consumers of the Rainbow

Serpent symbol, reading in it positive messages about the earth and

people’s spiritual relationship with it. Anthropologist Sallie Anderson has noticed that:

The authors of many New Age books on Aboriginal culture and spirituality pick and choose characteristics from ethnographic descriptions of various rainbow serpent myths that seemingly support their comparisons with the Kundalini, electromagnetism, Vishnu, fertility and death, vibration and energy sources and various other themes.

Raimbow Tomcat, Wikimedia Commons

The Rainbow Serpent’s winding form and brilliant colours have become a commonplace symbol within Australian pedagogical, cultural, economic and built environments.

This widespread familiarity with the image, and the apparent tangibility of the concept in its domesticated and aestheticised form, has led to it being understood as a preeminent symbol of Aboriginal identity, especially apparent in public

events celebrating the centenary of Federation.

The turn of the century saw a groundswell of interest in Aboriginal

people and their place in Australia. The first year of the new millennium

was supposed to mark the end of the ten-year journey towards

reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia.

In June 2000, hundreds of thousands had participated in the Walk for Reconciliation

and in September Australians cheered for Indigenous athlete Cathy

Freeman at the Sydney Olympics. These milestones meant that a feelgood emblem of the newly reconciled nation was needed for 2001, when Australia’s national identity was celebrated in the centenary of Federation. The Rainbow Serpent was called into service.

On 1 January 2001 the Journey of a Nation – Centenary of Federation parade through the streets of Sydney included a float shaped like a huge coiled snake, with dancers wearing costumes decorated with Rainbow Serpents designed by Bundjalung artist Bronwyn Bancroft.

Rosebank Public School

Then, at Canberra’s 2001 Floriade festival, the Rainbow Serpent again

appeared, this time in the “Century in bloom” display. On this

“floral walk through the decades”, viewers passed through plantings of

humble vegetables representing the hardships of the Depression and

beds of flowers planted in the shapes of the German Iron Cross and

the Japanese Rising Sun, indicating World War II.

The 1970s were represented by a display of tulips and native flora planted in the design of the Rainbow Serpent, ostensibly symbolising “Australia’s Aboriginal

heritage”. These examples suggest that the Rainbow Serpent was used

by the event organisers as a metonym for Aboriginality, so audiences

could embrace Aboriginal peoples’ place within Australia’s national

identity.

However, the Rainbow Serpent was also used to symbolise Australia as a whole, and not just its Indigenous peoples. In Sydney’s annual New Year’s Eve fireworks display, the grand finale is always the lighting of the mystery symbol that adorns the eastern side of the city’s beloved Harbour Bridge. In 2001 that symbol was the Rainbow Serpent, depicted alongside the Federation Star. The maxim of that

year’s show was “100 years as a nation, thousands of years as a land”.

Thus the Rainbow Serpent was used to give modern Australia an

ancient past, and, in conjunction with the star, was appropriated to

represent Australia.

The use of the Rainbow Serpent was no doubt well intentioned, but this plainly benevolent and amorphous meaning was far removed from that connoted by the original, highly ambivalent Rainbow Serpents of the Dreaming.

Newtown graffiti/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Aboriginal people have also adopted new symbolic meanings for the Rainbow Serpents. Due to the history of colonisation and the emergence of Indigenous political organisations and media, Aboriginal societies have become more mixed and cosmopolitan, and a pan-Aboriginal identity has emerged.

Instead of identifying solely with one’s clan or language group, Aboriginal people have formed a community that encompasses the entire continent. As such, they have needed to develop their own symbols to represent this new pan-identity, and the ubiquity of the Rainbow Serpent in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies makes it well placed to act as “a symbol of unity … amongst urban Aborigines”.

The image of the Rainbow Serpent has been used in a number of ways. The Rainbow Serpent has provided a logo for Aboriginal corporations such as the Northern Land Council. Victoria’s Rumbalara Oral Health Centre depicted the Rainbow Serpent as dental floss, “twisting through

an orange tangled web, which represents plaque on teeth”.

For the Aboriginal community of Moree, it was a symbol of unity when they constructed a 17-metre long Rainbow Serpent for the Black + White + Pink Reconciliation Float, entered in the 1999 Mardi Gras parade.

David Hancock/AAP

Inscribing new meaning

The Rainbow Serpent has been an important symbol in Aboriginal societies for thousands of years, and by the start of the 21st century it was also a recognised symbol for the wider Australian society. In making that transition it lost its particular “traditional” meanings of creation, water and fertility, and its ambiguous combination of creative and destructive forces.

Although it has not featured much on the national stage as a symbol since the Federation centenary in 2001, it remains a potent symbol of local Aboriginal community spirit and reconciliation. For example, Bundjalung artist John Robinson’s

Rainbow Serpent artwork was installed at a shopping centre in East Maitland, New South Wales to celebrate 2018’s Reconciliation Week.

In 2019 a Rainbow Serpent water feature designed by a collective of Kamilaroi women artists was commissioned for the Gunnedah Civic Centre, and the Perth Royal Show showcased a public performance by Noongar elder Walter McGuire, featuring a “35m long Wagyl inflatable creation … illuminated by the colours of the rainbow”.

It is evident then, that the supple skin of the Rainbow Serpent continues to provide an ideal canvas for inscribing new meanings and symbolisms for both

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

This is an edited extract from Symbols of Australia: Imagining a Nation, edited by Melissa Harper and Richard White, published by NewSouth Books. Footnotes for this article can be found in the book.

![]()

Shino Konishi receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Friday essay: creation, destruction and appropriation – the powerful symbolism of the Rainbow Serpent – https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-creation-destruction-and-appropriation-the-powerful-symbolism-of-the-rainbow-serpent-169934