ANALYSIS: By Jonathan Ritchie, Deakin University

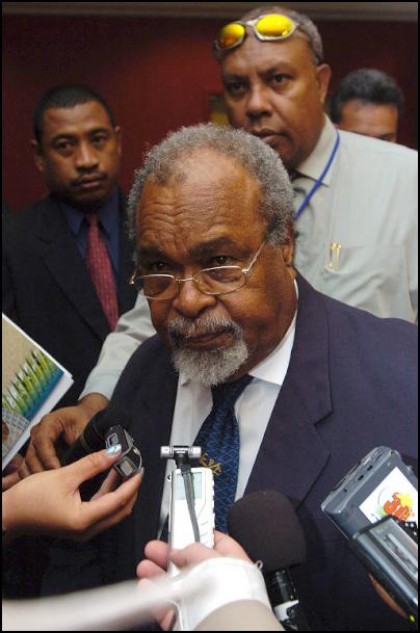

Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, former prime minister of Papua New Guinea and a giant of Pacific politics, has died from pancreatic cancer. He was 84.

Known as “Mike” to some and “the chief” to others, Somare in more recent years became widely referred to as “the grand chief” – the highest position in his nation’s honours system.

In his long career, Somare dominated PNG and Pacific politics.

He was regarded as the “father of the nation” for his role in moving PNG from colonial dependency of Australia to a fully fledged independent state. He helped build a nation that sits at the meeting point between the Pacific and dynamic East Asia with all the strategic, economic and cultural issues that brings.

Somare was the colossus of PNG’s political landscape: chief minister from 1972 to 1975 while the country was still an Australian-administered territory, its first prime minister (1975-1980), as well as its third (1982-85) and 12th (2002-2011, although some consider that his term concluded in 2012).

In fact, for 17 of PNG’s 45 years since gaining independence – more than a third of the period – Somare was its leader. When not in this role, he was very much the power behind the scenes, kingmaker, sometimes troublemaker and – often – peacemaker.

In 1967, Somare joined with other young nationalists, discontented and angered by the slow progress towards independence from Australia, to form one of PNG’s first political parties, the PANGU Pati (Papua and New Guinea United Party). Their criticism of the worst kind of Australian paternalism brought them attention from the colonial authorities, which Somare wrote about using a pseudonym.

PANGU’s mild politics

In truth, PANGU’s politics were of the mildest variety. When anti-colonial movements in other places were pursuing armed revolution, Somare and his fellows – always a small group of educated (and thus, elite) Papua New Guineans – forecast merely:

[…] if the present system of colonial or territory government continues, with all its inevitable master-servant overtones, serious tensions will develop.

They then made modest calls for self-government by 1968.

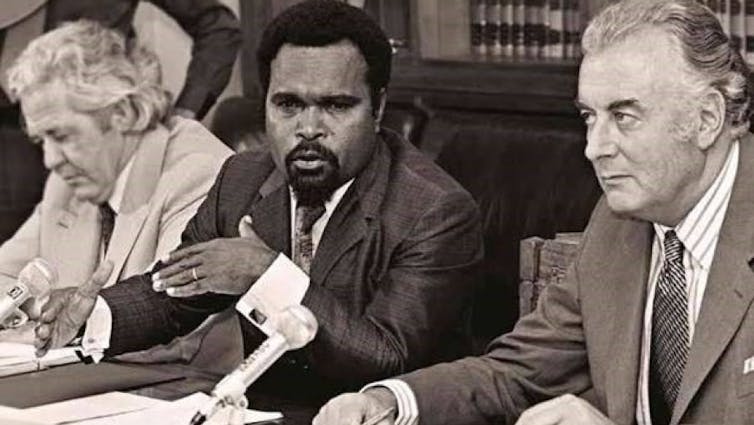

When Somare and other PANGU members were elected to PNG’s territorial House of Assembly in 1968, they formed an unofficial opposition to the administration. In April 1972 – before the election of the Whitlam Labor government in Australia – PANGU, with Somare as leader, was able to form a coalition that took the territory to independence in 1975.

In that year, Somare – amazingly – found the time to write his autobiography, Sana, which records his journey from his village in the Murik Lakes area of the Sepik River to becoming the nation’s first prime minister on the eve of PNG’s independence. The book provides a first-hand account of PNG’s path to self-government and nationhood, importantly from the perspective of the colonised.

Always a strong communicator, Somare used the book to foster pride among Papua New Guineans in their own nation, which gained its independence in a way that was both constitutional and peaceful. As its first governor-general, Sir John Guise, famously pronounced on September 16 1975, PNG Independence Day:

[…] we are lowering the flag of our colonisers […] not tearing it down.

The way PNG gained its independence owes a great deal to Somare’s careful devotion to the spirit of sana: a word from his people’s language that denotes taking a peaceful, consensual approach to resolving disputes.

In the face of a colonial system that was often stubborn and narrow-minded, and amid an expatriate population – overwhelmingly Australian – who were too often discriminatory and racist, he could have chosen a path of violent resistance. Instead, he chose the way of peace, of toktok (Tok Pisin for discussion) and of consensus.

‘Radical, red-ragger’

Even as a young leader, described in British government confidential notes as “a radical and red-ragger”, he believed in words over guns. It was a quality that was demonstrated in his handling of the separatist movement in Bougainville, which threatened to divide PNG even before it gained independence.

As well as drawing on the principle of sana to keep the nascent state together and prevent secession, Somare’s greatest achievement was bringing a reluctant people to embrace the creation of their nation.

Aided by a body of capable and committed PNG leaders in the Constitutional Planning Committee (CPC) that he established soon after becoming chief minister in 1972, Somare set out on a mission to develop a constitution that was, in his words “home-grown”.

The CPC was given the task of consulting widely with Papua New Guineans in their highlands and islands, to ensure they felt their wishes and beliefs would be fully reflected in the new nation’s foundational document. By the time of independence in 1975, it is reasonable to say this goal had been achieved.

The recently retired secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), Papua New Guinean Dame Meg Taylor, recalled of that time:

It is perhaps presumptuous for me to say that I was a constitution‐maker, but in some respects we all were. Anybody who went to a CPC meeting […] was a constitution-maker.

In following the principles of sana – consensus, discussion, inclusion and peaceful resolution of conflict – Somare was adhering to a way of dealing with others that is shared across the Pacific region. It is appropriate that Taylor, who learned about sana from working closely with Somare, should have held to these principles in her role as PIF secretary-general.

Shared identity across Pacific

With her retirement from this role, and even more so with the death of Somare, there is a pressing need for some sana to be deployed, to hold this important Pacific regional organisation together. Toktok, talanoa, or just conversation that recognises a shared identity across the Pacific from West Papua to Rapa Nui (Easter Island), is needed.

It is a tragedy that perhaps the greatest exponent of this – Michael Somare – has left us. His life spanned the modern history of PNG and now, more than 45 years after his nation gained independence, his influence remains profound.

He will be remembered as a quiet but persistent champion of his people. In a region that is dominated by superpower rivalry and challenged by climate change, perhaps we would all do well to learn from his example and practise more sana.![]()

Dr Jonathan Ritchie, senior lecturer in history, Deakin University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz