Analysis by Manqing Cheng – Doctoral Researcher in Politics and International Relations at University of Auckland. This is Manging’s first analysis for EveningReport.nz.

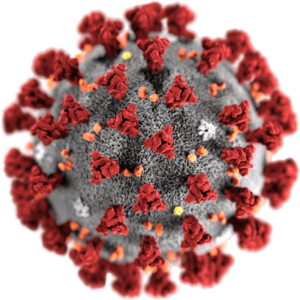

Precis: This article takes the WHO as an example to examine the difficulties for some international organizations in playing their due roles and tackling with the security threats of international concern such as a public health crisis of COVID-19. It is believed that an in-depth institutional reform is necessary for international organizations including WHO to adapt to the reset of globalization, the ensuing global challenges, and the transformation of global governance in the post-pandemic order.

Confronting the public health crisis as COVID-19, the existing global governance system has fallen into a state of partial failure, which is embodied in slow response and action of international organizations, increasing difficulty in coordination and cooperation between big powers, and the lack of leadership. WHO is clearly unable to coordinate national actions or to regulate behaviour and change prevention and control measures of various countries amid this pandemic. In recent years, the impediments to globalization, the rise of populism, the revival of nationalism and unilateralism allude to the inherent conflicts between international organizations and sovereign states. Disease is a non-zero-sum non-traditional security issue as its threat to all is undifferentiated. Since everyone is facing a common threat, international organizations that are instrumental for communication and preventive solutions should take the lead. But why some international organizations failed to function and why can it be hard for countries to utilize such platforms and work together? This article analyses that there are several major dilemmas restraining the role of international organizations, which are unlikely to be resolved in the short run. The following takes WHO in the pandemic as an example to explore its plight.

Difficulties and Dilemmas Confronting International Organizations

Above all, the WHO faces constraints from the sovereign states.

The first hinderance is financing. The most common way for all parties to play games in WHO is to influence the WHO agenda through financial leverage. WHO’s funding comes from two main sources: assessed contributions and voluntary contributions largely from member states and other sources such as philanthropic foundations and private sector. Assessed contributions have been a declining share of WHO’s overall budget in recent years, so the organization is increasingly relying on voluntary contributions. The trick is that most voluntary contributions come with explicit requirements and restrictions on their use. The only fund that WHO really has control and can flexibly allocate is about US$500 million a year in assessed contributions. WHO has been struggling to both invest in global public health and to cover its own operating costs. Take the 2018-2019 biennial budget as an instance, the total planned amount was US$4.422 billion (the actual implementation was US$5.3 billion), of which the assessed contributions were only US$957 million. As the biggest contributor to WHO, after President Trump announced a suspension for US funding on April 14, 2020, Director-General Tedros indicated that the US move would leave the organization with a financial gap that could interrupt the efforts to stop the coronavirus pandemic. When the greatest power takes an example, it is hard for others not to follow suit, particularly under the situation where all economies are suffering heavy losses.

The second is the recognition. As an intergovernmental organization, WHO has the legitimacy and capacity to act only based on state empowerment and authorization. In a broad sense, this “authorization” is also a recognition. A recognition of the existence and effectiveness of international organizations. Given the limits of human knowledge of various communicable diseases, WHO remains torn between taking initiative and being cautious in the event of an outbreak. After the outbreak of influenza A (H1N1) in 2009, WHO coordinated countries to take proactive measures and declared a “pandemic”, but was accused of “overreacting”. This was because H1N1 had been spreading all over the world, but the fatality rate was low. A joint report by the British Medical Journal and the Parliament of the European Commission criticized WHO for exaggerating the pandemic, causing panic among the public and triggering a global rush to buy vaccines for pharmaceutical companies to profit. After the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, WHO was accused of poor early warning, ineffective prevention, and slow response. Critics claimed that the first Ebola patient was infected in Guinea in December 2013, but WHO did not officially declare an outbreak until three months later, when the virus had spread to neighboring countries. In this recent crisis, WHO’s status and value have been further weakened. During the present anti-pandemic process, the Trump administration continuously accused WHO of acting too slowly to sound the alarm about the coronavirus. A great power refuses to admit the role of WHO is parallel to not recognize and distrust the organization, which will inevitably impact the international organization’s authority and capability to act in its field. Facing public health threats, particularly from unknown viruses and emerging infectious diseases, WHO seems to be caught in a paradox: taking aggressive action to stop outbreaks before the situation becomes serious will be criticized as overreacting; and taking cautious attitude would be blamed for failing to contain the pandemic. The anarchy of international system makes international organizations have no coercive power in implementing measures. One of the authoritative sources of them is the level of expertise rest on knowledge. They hold the “power” to master data, publish information and set standards by virtue of their knowledge. Therefore, if a country questions its expertise, it can affect a range of the organization’s actions. If countries no longer use that knowledge as a standard, the authority of the organization will be undermined.

Secondly, the WHO is influenced at the systemic level.

First of all, international organizations are the product of globalization and multilateralism. In theory, the deepening of globalization should become a hotbed for the development of international organizations. In reality, nevertheless, globalization has deepened the antagonism between countries. We are witnessing more clearly the gap between countries and the changing political landscape within them. Some countries have risen in the process of globalization, while others have been divided in the process. Rising nations are more insistent on globalization, while declining nations only want to retreat. International organizations seem to become a burden no longer needed, living in the tension between the cracks. As a sub-agency of the UN system, WHO seeks to place health goals above power politics. But as an intergovernmental organization, WHO cannot avoid the shades of power game and geopolitics. As early as its establishment, the Constitution of the World Health Organization was delayed by the ratification of member states due to the confrontation between two camps of the U.S. and the Soviet Union. It was not until the outbreak of cholera in Egypt’s Suez Canal area that countries realized the importance of establishing a global public health organization and passed the Constitution in 1948. With the launch of the Marshall Plan, the eastern and western camps entered a period of fierce confrontation. In 1949, the Soviet Union led the Eastern European countries withdraw from WHO. In order to maintain the integrity of global public health system, then Director-General George Brock Chisholm retained the membership of the Soviet Union and other countries on the ground that there was no opt-out clause in the Constitution, so that the Soviet Union was able to rejoin in 1958.

Second, the new world pattern is evolving, and some countries are inclined to politicize global issues. The alleged politicization of health issues refers to use health issues as a tactic to pursue political goals. The introduction of political issues into WHO by some countries led to the dysfunction and overloading of the mechanism beyond WHO’s jurisdiction and weakened its original purpose of promoting public health. When Trump halted funding for WHO, he also expressed his dissatisfaction and anger at WHO’s repeated praise for China’s anti-epidemic efforts. He believes that the U.S. is investing a lot of money, but WHO is ultimately standing up for China. International organizations do not necessarily choose sides, but their support for one country in a certain area may be regarded as a preference to be resisted by the other party. WHO, in this case, is unwittingly entering the political gap between China and the U.S. Mutual recriminate and stigmatization, transfer domestic contradictions as well as shirk responsibility for the poor response to the pandemic aggravate the conflicts and frictions that already existed among member states, thereby result in the inefficient operation of international organizations. In this climate of mistrust and disunity, it is hard for all parties to act in concert.

Third, non-neutral rules of global governance are impacted. The current global governance system mainly relies on the rules formulated by western countries. However, these rules are non-neutral in the light of non-western cultures. That is, the meaning of the same system varies to different groups, and those who benefit from the established system or may benefit from some future institutional arrangement will strive for or maintain institutional arrangements that are favorable to them. Global governance rules exist upon intersubjectivity and only play a normative role if they are accepted by the majority. Non-neutral rules are difficult to promote consensus between western and non-western cultures. One consequence of this non-neutrality is that in the practice of global governance, the actual benefits or losses brought by different mechanisms to sovereign states are inequivalent. In an era when the developed economies dominate in the global governance system, such non-neutrality, while has always existed, is not as prominent as it is today with more and more non-western economies rise and enter the global governance system. This is illustrated in the case of COVID-19 striking big powers, as non-western actors are bringing their own practical experiences into the existing governance system, thereby shaking the governance structure dominated by the Western instrumental rationality. The concepts, principles and approaches of global governance begin to fall short in attuning to the reality of rapid development of globalization and the emergence of global challenges.

Lastly, the WHO has self-deficiencies in terms of operating rules and mechanisms.

First, WHO is already the largest and most authoritative international agency for epidemic prevention in the world, but it is still unable to play a leading role in this crisis. This is because international organizations and states are distinct in nature. States have sovereignty, while international organizations do not. Management personnel in international organizations are dispatched by member states, and there are no individuals independent of the state and belong exclusively to an organization. This makes it impossible for international organizations to operate in complete isolation from states. Additionally, an international organization is a platform where member states gather for discussion, vote to reach a resolution, and implement it. Basically, the consensus of major powers becomes the resolution of the international organization. That is, a balance exists between the views expressed by the representatives of member states within WHO. Leaders of international organizations has only the power to implement the policy. Taking the position of chief balancer, Director-General Tedros may be viewed as a consensus-maker instead of an authoritarian decision-maker. International organizations, whether intergovernmental or non-governmental, are coordinating bodies. Their decision-making power is limited. Whether member states, especially the big powers, have shared interests, common needs and collective policy orientation determines how much role the international organization can play.

Second, WHO has an “institutional inertia”. Its reform of governing structure lags behind the development of global health governance with its influence on the decline. Since 1999, the principle of zero growth has been introduced into the budgeting process of WHO. Consequentially, WHO is increasingly dependent on voluntary contributions and has shown a bilateralism in promoting projects, since most contributions are earmarked for specific purposes by donors. As some scholars note, voluntary contributions militate against multilateral governance and decentralize the authority of international organizations to donor countries.

All in all, from the perspective of internal factors, academics generally believe that WHO’s organizational culture is strongly functionalist, conservative, and increasingly corrupt in recent years. The failure of strategic planning and the over-decentralization of WHO’s structure render its internal system increasingly rigid. Moreover, there are issues of impartiality within WHO. As more and more information about WHO’s internal decision-making is exposed by the media, the fairness and transparency of WHO’s work are increasingly questioned. Many scholars agree that the financial interests of the medical experts who advise WHO on decision-making are intertwined with multinational pharmaceutical companies, making WHO difficult to be objective and neutral.

To date, no substantive breakthrough and sustainable progress have been made in any area of governance, terrorism, financial crisis, transboundary disasters, and climate change, etc. COVID-19 represents yet another failure of global governance. The root cause is the lack of international cooperation. In recent years, with the strong backtracking of populism, unilateralism, and power politics, international relations are shifting toward geopolitics, the sense of international responsibility and the trust of international community are declining. It seems that everyone knows the theory of win-win cooperation, however in reality, the spirit of cooperation is easily concealed, forgotten, and even deliberately abandoned.

Some Recommendations on Institutional Reform in the Post-Pandemic order

In the post-pandemic world, international organizations and multilateral mechanisms will face greater tests. Only through constant institutional reform can they adapt to a changing world order.

The first is to boost the leadership and appeal to perform the leading and coordinating role to full potential in global governance. The authority and expertise of international organizations are mainly reflected in the fairness and effectiveness of promoting international cooperation and solving global issues. This depends on the sufficient cooperation and support of member states on the one hand and on the strategic vision, leadership, and professionalism of international organizations from officials to staff, on the other. In response to global challenges like COVID-19, the UN needs to make corresponding reforms and adjustments. This would include convening relevant meetings at the earliest possible time to convey confidence to the world, unifying the goals of all parties, and drawing up global action roadmap. Specialized agencies under the UN need to carry out separate actions around their respective themes, update their own rules and norms in real time. WHO could be more empowered to upgrade the global public health governance system. The international community has had conducted some effective bilateral and local cooperation and gained positive experiences in the fights against SARS, H1N1 influenza and Ebola, but there is still a long way ahead to achieve global, sustainable and closer cooperation. It is necessary to improve the overall status of public health governance and reinforce WHO, so that it has more rights and higher international status similar to that of the IMF and the World Bank to organize experts and focus on scientific research, vaccine development and data sharing as well as help developing countries with weak health infrastructure to improve their response capacity. The international community has generally been underinvesting in public health. As of February 29, the U.S. was still more than half behind with its 2019 dues and US$120 million is defaulted for 2020. After the outbreak, the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund has been created by the UN Foundation, the Swiss Philanthropy Foundation and WHO, but similar efforts should be more institutionalized in future. Meanwhile, WHO must strengthen the institutional construction, such as build a global infectious disease monitoring, early-warning and emergency-boot mechanisms, further elucidate the rules and norms of public governance, formulate guiding principles that all countries must abide by, unify standards, and improve the control and binding force on relevant behaviors of various countries, but not limited to report information, temporary research and judge the situation. For now, though the role and status of WHO in global public health governance has been weakened to a certain extent, as the largest international health organization and one of the larger specialized agencies within the UN, WHO still has broad responsibilities to combat infectious diseases based on the Constitution of WHO and designated by its accession to the UN, as well as has the only authorization of leading and promoting effective development of international health law. Therefore, it is crucial to carry out effective reform of WHO. The direction is not “reprimand and denounce” by some member states targeted others and counteract each other’s efforts. Instead, it should be further enhancing the power of existing multilateral mechanisms, increasing financial support, and expanding bilateral or small multilateral public health cooperation to larger regional domain. For this purpose, the established China-Japan-ROK joint prevention and control mechanism and the public health cooperation within the ASEAN framework should be consolidated and then upgraded to the Asia-Pacific region. The European Union and the African Union should also act together and promote the integration of public health, and then on this basis, form the regional cooperation between Asia and Europe, among Asia, Europe and Africa as well as in a wider range.

The second is to strengthen the authority and expertise of international organizations. Globalization has never been entirely positive as a single-dimensional process. International organizations is the central force and the primary driver for global governance. The multilateral cooperation mechanism should include at least two functions: political leadership and advisory implementation. In the current international system, it is unrealistic to require specialized agencies to perform core political leadership because they do not have corresponding political authority and power resources. However, for multilateral organizations with rich expertise in a specialized field, it is the fundamental obligation to provide intellectual support and technical implementation for political decision-making. For example, the political leadership of G20 and the advisory implementation of WHO could converge and form a global action model to counter security threats more actively in global public health. WHO can gather information, propose professional suggestions, and provide a concrete scientific basis for the G20 to put forward global action plans. In this regard, G20 could be continuously elevated from short-term crisis response mechanism to long-term governance mechanism.

Conclusion

International organizations have accrued deep malpractices in managing global affairs. In the current COVID-19 and previous international public health emergencies, there are various difficulties in the operation of international organizations, confining them to take conductive actions, which in turn reducing the effectiveness of problem solving. The world seems to lack a consistent and coherent response in the face of a common enemy. A path of transformation should be explored. Only through constant change can international organizations be reinforced in the new order, otherwise it will be eliminated or replaced. However, we must also be aware that some curtailments are beyond the scope of international organizations and concern the whole international community. The reality of the COVID-19 has put the international community at a crossroads once again. Is it to turn the crisis into an opportunity and make the pandemic a driving force for community building through strengthening all-round cooperation and multilateralism? Or to reject international cooperation, shrink into a corner, and deepen the division of the world? Or to expand the conflict and make the outbreak a pusher of the law of jungle? The rational choice is certainly cooperation. COVID-19 is an acute crisis that not only takes a heavy toll on global public health safety, but also creates global threats to varying degrees in other fields through its spillover effects. Institutional reform needs the solid support of political will and cooperative consensus. Multilateralism is by far the most reasonable approach to global governance, and multilateral cooperation is the most democratic way to combat global threats. Whether global consensus can be reached and cooperation mechanism can be built out of the crisis will not only directly affect the success of anti-pandemic battle, but also have a far-reaching impact on the international relations and world order after the pandemic.