Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Darius Sepehri, Doctoral Candidate, Comparative Literature, Religion and History of Philosophy, University of Sydney

In our series Art for Trying Times, authors nominate a work they turn to for solace or perspective during this pandemic.

Alfred Tennyson’s 1833 poem “Ulysses”, was, he tells us, written under a sense of loss — “that all had gone by but that still life must be fought out to the end.”

Dealing with the inertia created by grief, and the will needed to resist and move ahead, the poem perfectly expresses what St Paul called the “hope against hope”. Despite the heroism of the famous last line, (“To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”), the poem’s defiance only makes sense in the light of the anguish animating it.

Tennyson’s book-length elegy In Memoriam AHH, published in 1850, once among the most popular poems in English, came out of the same sense that the whole world was over — not a world but the world — and yet life must be lived, somehow.

I experience In Memoriam as a soulful and provocative artwork, not a “relevant” one or one merely to be mined for therapeutic consolations.Despite its formal control and elegance, and what we may hear as dated language, Tennyson’s long poem is tumultuous, chaotic, and not only personal but social, deeply connected with upheavals in Victorian society.

Read more: Ode to the poem: why memorising poetry still matters for human connection

Passion

Both Victorian and modern in style and composition, In Memoriam uses extraordinarily passionate language, tightly compressed. Its passion is directed by Tennyson at another man, his friend Arthur Hallam, a brilliant philosopher. Tennyson and Hallam met at university. We know their first encounters were magnetic and catalysing.

When Hallam died suddenly of a brain aneurysm in Italy in 1833, aged 22, it violently changed Tennyson’s life.

Tennyson took 18 years to write In Memoriam. The prologue and epilogue attest to unshakeable faith in Christianity and in life’s continuity. The prologue’s first line addressed to “Strong Son of God, immortal Love”, and the last lines professing the eschatological completion of the world in “one far-off divine event/To which the whole creation moves”, could hardly seem more assured.

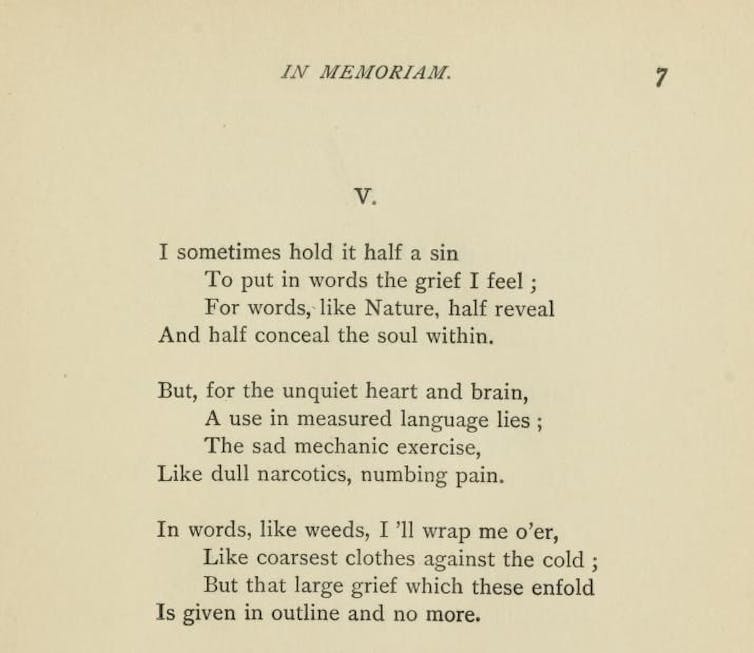

And yet. The 131 cantos in between these bookends trace an agonising journey into suffering, doubt, helplessness and the possibility of unredeemed pain that has no meaning or purpose. The rhetorical strength of some of these cantos is such that it puts the orthodox Christian position the poem professes elsewhere in serious question.

The way the poem tries to think through the many grand subjects it raises, such as if God cares for each individual being, creates a meandering journey, now confused, now suddenly clear. This feels right for grief.

The poem spirals around its ideas, rejecting clean linear progression, organised around three Christmas sections (cantos 28, 78, and 104) of heightened feeling. Coming back and back to things, seemingly obsessed, Tennyson speaks of “a loss for ever new”. There is no “closure” of the wound. Can Christ really fill it? The world and its goods cannot.

I’ve committed many parts of In Memoriam to memory, made easier by the poem’s exceptionally memorable language (immortal, melodious phrases like “I loved the weight I had to bear/because it needed help of love”).

The poem’s form, entirely in quatrains of iambic tetrameter rhyming abba, composed in a long, ledger-like diary now kept at the British Museum, aids in memorisation.

Read more: Explainer: poetic metre

I recite a selection of cantos here, and the famous “Ring Out Wild Bells” sequence, which charts a move from devastation to rebirth.

In Memoriam has an almost relentlessly regular meter, meant to recall biological processes such as the beat of the heart and breathing, organic processes that sustain life even as the poet’s being cries that life has ended.

All creation mourns

After Tennyson received a letter telling him Hallam’s remains were coming back by sea to Hallam’s family in England, he wrote the very first part of In Memoriam, calling the ship home: “Sphere all your lights around, above/Sleep, gentle heavens, before the prow/ Sleep, gentle winds, as he sleeps now.”

A hypnotic enchantment is created with the ship phosphorescent as it sails at night.

The poem connects something cosmic and transcendent with Tennyson’s own very private, enclosed grief. Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life, a film where the death of a young son is juxtaposed with grand existential and metaphysical questions that interrogate God, also aimed for such territory.

Soulful ambiguity

“Dear friend, far off, my lost desire”, cries Tennyson. Today if a man speaks such excessive language of love to another man, we are likely to apply a defined identity or classification.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and the complex life of the ‘poet of America’

Although modern readers may read Tennyson’s excessive professions of love for Hallam as homosexual, the nature of their relationship was unclear to Tennyson himself, and its expressions in keeping with Victorian sentimentality. He would have baulked at our collapsing of an entire world of feelings so complex.

In Memoriam testifies to the ineffability of human experience. Language is inadequate to capture its density and intensity.

Tennyson was protective of the intensity of his feelings: hence the time he took to publish. He avoided the imperative to immediately display. Today we feel immense pressure to respond at once, in public, with clear stances, to make things transparent. Such transparency destroys soulfulness.

What makes our times so hard to bear are not just external circumstances themselves but the common ejection of mystery and suffering from art, and transcendence from consciousness.

In Memoriam dwells with the mysteries of being and death, mounts an impassioned defence of love and friendship, and — perhaps rarest of all — reminds us of something noble in the capacity to suffer for an ideal.

Tennyson’s lavish, excessive passion, his “tarrying with the negative” as Hegel put it, shows us how soulful art stirs us to life and staves off banality — but the cost must be paid.

Tennyson had a deep interest in Persian poetry through his friend Edward Fitzgerald (translator of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam).

He surely found something in Persian poetry’s insistence that grief and joy are inseparable and that death is not total loss, because nothing we feel passionately and soulfully is truly lost to us.

– ref. ‘A doubtful gleam of solace’: reading Tennyson’s In Memoriam AHH in difficult times – https://theconversation.com/a-doubtful-gleam-of-solace-reading-tennysons-in-memoriam-ahh-in-difficult-times-143614