ANALYSIS: By Rizki Fachriansyah and Ary Hermawan in Jakarta

The Covid-19 pandemic situation is already bad in Indonesia, which now has the highest death toll in Southeast Asia just a few weeks after declaring itself “virus-free”. As of yesterday, Indonesia had reported 686 cases with 55 deaths.

The crisis is likely going to get worse. Experts predict that more than 70,000 Indonesians will have been infected by the disease as of Ramadan and Idul Fitri, during which millions of the country’s Muslims typically travel to their hometowns.

That number, according to one scientist, is a “conservative” estimate.

READ MORE: Does Indonesia need a lockdown? It depends on how you define it

The rapidly escalating health crisis has prompted the government to devise a variety of strategies – such as the practice of “social distancing” and the use of mass rapid testing – to avert an overwhelming health disaster.

Questions linger, however, about whether the measures taken by the government are enough to prevent the country from descending into a crisis of the scale now seen in Iran and Italy, where the death toll has reached thousands, or even worse.

– Partner –

Here is what Indonesia has been doing to fight the pandemic:

No lockdown, only ‘social distancing’

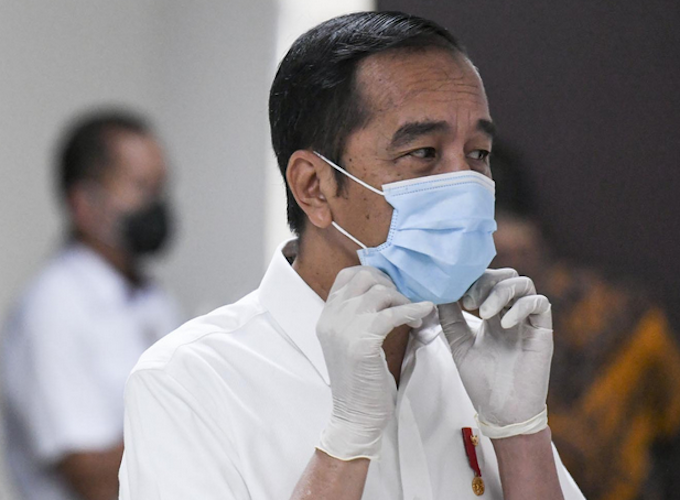

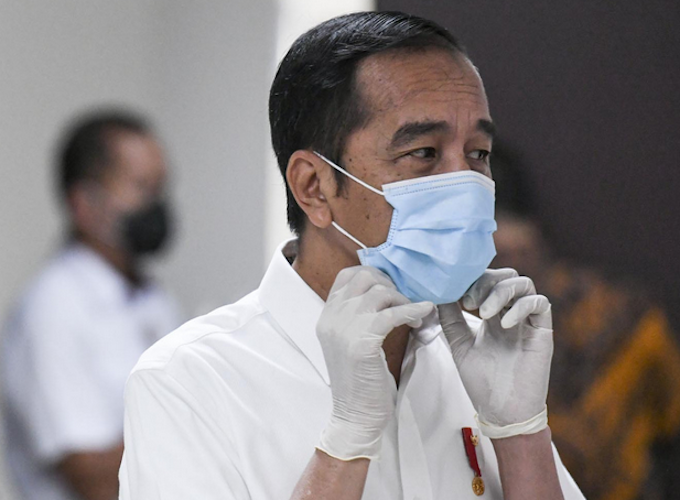

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo continues to stand by his initial statement that the government would not seek to impose any form of lockdown in the country, citing the lasting repercussions that such a policy would likely cause to the country’s social cohesion and financial stability.

Jokowi said the cultural characteristics and discipline of the Indonesian people were the two main reasons why the government had ruled out lockdown.

“I have gathered data about countries that have imposed lockdowns, and after analyzing them, I don’t think we should go that way,” the President said during a limited meeting at the Presidential Palace on Tuesday.

In lieu of issuing a strict lockdown protocol to control the spread of COVID-19, Jokowi insisted that social distancing, also called physical distancing, was still the most viable solution to the current health emergency. “The policy of physical distancing can halt the spread of the disease if people really comply with it,” he said.

Despite the central government’s aversion to lockdowns, the capital city of Jakarta has announced a state of emergency which entails restrictions that are similar to the ones normally associated with a partial lockdown, particularly Malaysia’s “movement control order”.

On March 20, Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan urged all stakeholders – including corporations, social organizations and religious groups – to take drastic action to prevent the spread of the disease during the state of emergency.

The administration has since closed all tourism spots and entertainment venues and has limited access to public transportation.

The National Police have also announced that officers will take strict action against people who gather in large numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The strict policies taken by the Jakarta administration and other regional administrations coupled with the police policy have raised suspicions that the government has imposed a partial lockdown on the country without saying so.

However, it is clear that Jakarta, which has become the epicenter of the outbreak in the country, has yet to prevent people from entering or exiting the city, allowing the virus to spread to other provinces in the country.

Cities from Sumatra to Papua are now reporting that their first confirmed cases had a history of recent travel to Greater Jakarta.

South Sumatra and West Nusa Tenggara reported their first cases on Tuesday while the provinces North Maluku and Jambi reported their first cases on Monday, with the majority of cases having recently returned from Greater Jakarta.

Mass rapid testing — a silver bullet?

Jokowi has opted to test large numbers of people for the virus with newly obtained rapid testing kits. The first testing campaign was conducted in South Jakarta, given the area’s particular vulnerability to the disease, according to contact tracing carried out by the authorities.

It is believed that Indonesia is attempting to follow in the footsteps of South Korea, which has ruled out a lockdown and has become a model to other countries for the massive and sophisticated testing and tracing strategy it employed to handle the crisis.

The rapid test, which detects patients’ antibodies to the pathogen, is considered more convenient and can detect whether someone has been infected with Covid-19 much more quickly than the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

The rapid test requires only blood serum as a sample, meaning the tests can be performed at health laboratories throughout the country.

Everyone, whether they have shown Covid-19 symptoms or not, can be tested. In contrast, regular PCR tests have to be performed in level two biosafety laboratories, since nasal fluid or larynx substances must be used as the main specimens.

On Monday, West Java Governor Ridwan Kamil announced that the provincial administration would conduct rapid tests in sports stadiums as soon as the region received testing kits from the central government.

Out of the 55 confirmed cases in West Java, 41 are from Bogor, Depok and Bekasi as of the time of writing.

The problem is, experts say, that Indonesia might not have the testing capability of South Korea, which has used mostly PCR-based testing to aggressively trace and isolate infected patients.

Indonesia has relied heavily on antibody test kits, which give immediate results but are less accurate and can only begin to detect the disease five days after infection.

Padjajaran University epidemiologist Panji Fortuna Hadisoemarto argued that by relying on antibody test kits for the mass testing campaign, Indonesia would not be able to replicate the strategy used by South Korea to “find and destroy” the chain of infection.

“It is true that we don’t have sufficient PCR capacity. But we have to be mindful about rapid testing’s shortcomings as well. With antibody tests, it’s going to be a completely different game we’re playing. We’re not playing South Korea’s game; that’s for sure,” he said.

Health care system at risk of collapsing

The unprecedented pandemic has already thrown Indonesia’s health care system into disarray as many of the country’s 132 designated COVID-19 referral centers have struggled to accommodate the surge in patients.

Severe shortages of medical supplies, including protective health gear, have been a common complaint among health workers on the front lines. Reports of doctors being infected with, and subsequently succumbing to, Covid-19 have also continued to surface, stoking controversy about the level and quality of state support that health workers have received.

University of Indonesia public health expert Hasbullah Thabrany urged the public to comply with the government’s social distancing policy to flatten the infection curve and thereby prevent the system from becoming overloaded.

“Frankly, I don’t think we are equipped enough as it is to deal with further escalation. There are only 1,200 lung specialists in the country who are proficient in examining respiratory illnesses caused by the virus. The mitigation should be viewed as a collective endeavor with active participation from the public,” he said.

Of the country’s 579 confirmed Covid-19 cases and 49 fatalities reported as of Tuesday afternoon, it remains unclear how many were front line medical workers. The Indonesian Medical Association (IDI) has said that at least seven of its members have fallen victim to the virus.

In response to the crisis, Jokowi said the government would provide financial incentives, as well as additional supplies of protective gear, to ensure the safety and security of health workers while they do their jobs on the front lines of the pandemic.

The government is to provide a Rp 15 million (US$886.79) incentive to medical specialists, Rp 10 million to physicians and dentists, Rp 7.5 million to nurses and Rp 5 million to other medical staff members, he added.

“We will also provide a total of Rp 300 million for compensation in case of death. This applies to regions that have declared a state of emergency,” Jokowi said on Monday.

The government distributed 105,000 pieces of protective health equipment on Saturday to hospitals across the archipelago. Medical aid from China arrived in Jakarta on Monday morning in a government-to-government cooperation effort.

The Indonesian government has also established a new emergency hospital in the four apartment towers of the Kemayoran Athletes Village in Central Jakarta – used as the athletes village for the 2018 Asian Games – to alleviate the burden on hospitals facing an influx of COVID-19 patients.

The hospital, staffed mostly by doctors and nurses from the Indonesian Military and the National Police, has been fully operational since Monday evening and is expected to treat as many as 24,000 patients. The hospital will be able to handle about 3,000 patients at a time, Jokowi said.

Lockdown should not be off the table

Scientists, however, have called on the government to do more than just campaign for social distancing and mass testing to flatten the infection curve and prevent the Indonesian health care system from being overwhelmed.

Disease surveillance and biostatistics researcher Iqbal Ridzi Fahdri Elyazar and his team at the Eijkman-Oxford Clinical Research Unit (EOCRU) have said that, based on their calculations, Indonesia could be grappling with up to 71,000 COVID-19 cases by the end of April.

Hadi Susanto, a professor of applied mathematics at the University of Essex in England and the Khalifa University of Science and Technology in the United Arab Emirates, has given an even grimmer prediction.

Assuming that even after a lockdown is imposed people are still working and conducting business as usual, 50 percent of Jakarta’s population could be infected within 50 days after the first case was announced by the President on March 2, he said, adding that it was a “pessimistic” forecast.

Nurul Nadia Luntungan, a public health expert at the Center for Indonesia’s Strategic Development Initiatives, said that for regions with apparent community transmission, such as Jakarta, a partial lockdown could be imposed in parallel with mass testing efforts.

A lockdown, she said, was necessary to prevent the virus from spreading within the city and into more regions across the country, given the high mobility of people in Jakarta.

Panji concurred with Nurul, saying that a lockdown would still have to be imposed. “It has to be planned carefully. But it cannot wait.”

Rizki Fachriansyah and Ary Hermawan wrote this article for The Jakarta Post.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz