The Rappler video feed on the Ampatuan convictions last month.

For decades, the feared Ampatuan clan held sway in the impoverished province of Maguindanao in Mindanao in the southern Philippines. Through a ruthless private army and a reported “propensity for beheadings”, the clan cultivated a culture of impunity. Now, however, reports David Robie, a courageous judge has challenged the horror by jailing the masterminds of the 2009 Ampatuan massacre for life.

SPECIAL REPORT: By David Robie in Manila

The families of the 58 victims – 32 of them journalists or media workers – had waited for 10 years for justice in the Philippines.

After so long, what is another couple of hours?

The Ampatuan massacre in Maguindanao on 22 November 2009 was the world’s worst single attack on journalists and the worst elections-related violence in a country notorious for electoral mayhem.

READ MORE: The Ampatuan massacre – what happened and why

– Partner –

With the judge almost two hours late in arriving at the fortified special courtroom in Camp Bagong Diwa, a police barracks with a jail annex in Manila’s satellite Taguig City, fears were expressed for her safety.

The 101 accused (although three were missing and cited for possible contempt of court) for the heinous crime, dressed in yellow jail tees, were housed in in a barred cage sandwiched between lawyers and some 200 heavily armed police guards and waiting.

The lawyers for both prosecution and defence were waiting.

The media crews for the CNN Philippines live broadcast anchored by celebrity Pinky Webb were waiting.

The CNN Philippines live newsfeed on the Ampatuan judgment.

Live television

The public, glued to their television sets or live streaming from CNN and the state-run People’s Television, were waiting.

In the end, the historic judgment took only 52 minutes.

Many of the victims’ families burst into spontaneous applause for the jailing of the ringleaders; others wept for joy with the convictions. While other families of some of the accused were relieved with the acquittals.

Judge Joycelyn Solis-Reyes of the Quezon Trial Court Branch 221 announced to the court that she could deliver the shortened verdict rather than the full 761-page judgement or “it could take all day”.

In fact, broadcaster Peter Musngi reckoned it would have taken “43 uninterrupted days” to read the full judgement. Both prosecution and defence lawyers agreed to the short reading with the full judgment being made available online – read it here on Rappler.

Judge Solis-Reyes sentenced the 28 principal accused – including three brothers of the powerful Ampatuan warlord clan from Mindanao – to life in prison without parole and ordered them to pay a total of more than 155 million pesos (almost NZ$5 million) in changes to the heirs of 57 victims killed in the massacre.

The judge reduced the “official” death toll from 58 to 57 because the body of photojournalist Reynaldo Momay was never found. This means that the Momay family was not granted compensation even though it was commonly known that he was with the journalists who were killed and never been seen since. There was also dental evidence linking him found at the multiple murder scene.

Appealing sentences

Some of those jailed announced last week that they are appealing against their sentences, and the prosecution is also appealing over the acquittals and the judge’s Momay finding.

While it has been a long wait for justice for the victims, it had also been a long wait for the judge herself. Judge Solis-Reyes had shelved her own plans for career advancement so that she could see the notorious case through to judgment.

She was forced to brave death threats and political pressure over the case. At least three witnesses were killed during the course of the trial.

The judge had earlier admitted in interviews that she had wanted to pursue a career in broadcast media and had studied journalism at the Lyceum of the Philippines.

Describing the atmosphere in the courtroom with 400 people packed in to hear the verdict of the century” on December 19, Tempo columnist Jullie Y. Daza wrote that the judge “deserves the nation’s gratitude for her dedication and deportment”.

“All I can say is,” she added, “you’re priceless, Your Honour.”

Judge Solis-Reyes broke down her summary into 1. Those guilty beyond reasonable doubt; 2. Accessories; 3. Those released on the basis of reasonable doubt; 4. Those facing arrest warrants.

Police officers acquitted

Forty-three people, including leaders of the Ampatuan clan, were convicted of mass murder or being accessories, and 58 other accused – many of them police officers – were acquitted in the infamous case.

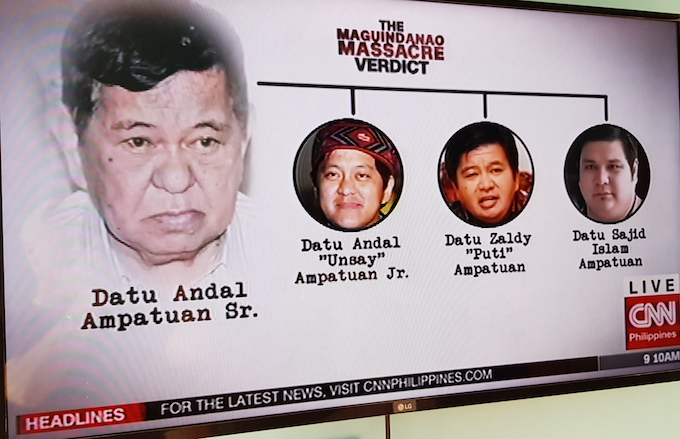

Sentenced to reclusion perpetua, or up to 40 years in prison without parole – effectively life – on 57 counts of murder were prominent clan members Datu Andal “Unsay” Ampatuan Jr; his brothers, former Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) governor Datu Zaldy “Puti” Ampatuan Sr, and Anwar Ampatuan Sr, former mayor of Shariff Aguak town.

Another brother was acquitted. Two other prominent members of the clan – nephews Anwar Ampatuan Jr and Anwar Sajid Ampatuan – and 23 others were also found guilty of the multiple murders.

Fifteen other accused – almost all of them policemen – were convicted as accessories to murder and sentenced to between six and 10 years in prison.

It took 10 years, 424 trial days, to hear the testimonies of 357 witnesses against 197 who were originally charged.

During the long-running trial, six accused were acquitted and the clan patriarch, Andal Ampatuan Sr, also accused, died in prison from a sudden heart attack in 2015, aged 74.

One of his daughters, Rebecca, told the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) that her father had six wives and 40 children. The PCIJ closely followed the case for a decade with a series of special reports in The Maguinado Chronicles.

The killings in 2009 sent shockwaves around the world because of the brazenness of the attack. The victims, including 20 women, were kidnapped and clubbed before they were executed, mutilated and buried in shallow graves.

Mass graves

The backhoe digger, using a government machine, who excavated and filled the mass graves, was among the convicted accessories.

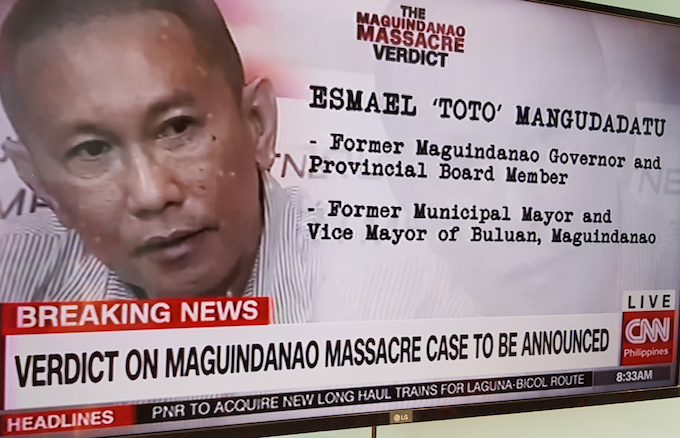

The ambushed electoral convoy had been taking the registration papers to enable challenger Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu to contest the governorship of Maguindanao in defiance of threats by the Ampatuans. He was not with the convoy, but his wife, Genalyn, was shot 17 times: “They shot her on her breasts, her private parts. Such unimaginable cruelty.”

He subsequently won the election in a landslide in 2010 and has since been elected to the Philippine national Congress.

The mass murders were widely condemned around the world by governments, global media freedom organisations and human rights groups. The US ambassador at the time, Kristie Kenney, described the killings as “barbaric” and then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon condemned the brutal political violence in the southern Philippines.

The Malacañang presidential palace welcomed the convictions last month, saying the rule of law had prevailed in closing one of the darkest chapters of Philippine history.

“The Maguindanao massacre marks a dark chapter in recent Philippine history that represents merciless disregard for the sacredness of human life, as well as the violent suppression of press freedom,” said presidential spokesman Salvador Panelo, who ironically was once one of the lawyers for the Ampatuans.

“This savage affront to human rights should never have duplication in this country’s history.”

Editorial opinions cautious

However, most editorial opinion in the nation’s media and human rights groups greeted the “historic” judgment with caution.

“Justice at last, but …” summed up the headline on a Philippine Star editorial, warning “a victory has been achieved, but the pursuit of justice is far from over”. Said the Star:

“Amid the rejoicing are the disappointments and concerns about what might happen next. With 56 defendants cleared, including two members of the Ampatuan clan, there are valid concerns raised by the victims’ families that violence remains a serious threat in the clan’s turf.

“Most of the guns believed owned by the Ampatuans and their private army remain unaccounted for. The claim is believed to continue enjoying control over substantial funds and other assets.

“Harassment of witnesses, victims’ relatives and prosecution lawyers are possible. At least three witnesses were killed in the course of the trial.

“There are 80 suspects still to be brought to justice, and an appeals process that could take another decade to complete. There is the equally complicated task of going after the assets of the Ampatuan clan.

“There are other criminal cases – about 200 of them – still being pursued, including complaints for corruption and obstruction of justice, as well as cases related to the murders and disappearances of witnesses.”

‘Terrible crime’

The Philippine Daily Inquirer noted in an editorial that this daily newspaper – along with other media – had “faithfully reported on the terrible crime that thrust the Philippines squarely on the map for the single deadliest attack on journalists in the world.

“In bearing witness, we strived mightily to ‘piece together the bloody shards of the crime’, and to find the words to ‘approximate the horror’.

But the Inquirer added that there were significant lessons to be learned – and acted upon – in spite of the hope stirred by Judge Solis-Reyes’ guilty verdicts, such as the “endless delay” caused by defence motions that reflected the “dismaying state of the judicial system”.

“And journalists and media workers remain in peril in the fast-shrinking democratic space.”

Philippine Star columnist Ana Marie Pamintuan described the Ampatuan clan as “Monsters Inc.” and was candid in a wide-ranging article about the challenges ahead after the judgment.

One challenge is to “catch the 80 suspects who remain at large and bring them to justice”. Another is the expected “spirited fight for their acquittal” on appeal for those who were convicted.

“Let’s hope the road to final judgment won’t take another 10 years,” warned Pamintuan.

Another huge challenge is the legal fight to have the Ampatuans’ massive wealth forfeited by the state, and payment of civil damages to the victims’ families.

Property freeze orders

Freeze orders have been issues by the courts on bank accounts, real estate property and other identified assets of the Ampatuan clan.

“Prosecutors believe, however, that substantial amounts of cash have been stashed away by the clan the old fashioned way – not in banks where there is a paper trail, but perhaps in boxes, chests or baul [a Tagalog word meaning a traditional clothes trunk], buried somewhere or concealed within walls the way South American narcos do with their mountains of dirty money,” says Pamintuan.

“In one of the poorest regions in the country, the Ampatuans thrived, driving around in convoys of luxury vehicles with their private armies, living it up in fortified mansions. How do local executives in third-class municipalities and impoverished provinces, with their modest salaries, manage to accumulate that kind of wealth?”

The last challenge – and probably the toughest – is how to “eliminate the environment that creates monsters and breeds impunity”?

Etta Rosales, former chair of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights, described the Mindanao environment as like the “wild, wild west”, warning it remained “compromised injustice” until the private armies and political dynasties were rooted out.

While the Ampatuan massacre remains the worst example of this environment, there are many other regions of the Philippines where the local population are ruled by patronage and fear.

The implications for press freedom in the Philippines have not been lost on students and tertiary journalism schools.

‘Already afraid’

Writing on Rappler, Diwa Donato, a political science graduate from Saint Louis University, Baguio City, who has dedicated 13 years of her life to campus journalism as an advocate for youth empowerment, press freedom and democracy, says she will never forget the day of the massacre. She was aged 10 at the time – and she was “already afraid to continue my dream of pursuing journalism”.

“The Philippines remains one of the deadliest countries for journalists in Southeast Asia,” she says.

“The fight of professional journalism will always be the fight of campus journalism. We celebrate the Ampatuan massacre verdict, hope for justice, and continue to address the struggles of press freedom.

“For now, democracy and press freedom have won. But we do not fight to win, we fight to be free. There is more to be done.”

National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) chair Nonoy Espina also fears for the future.

“The culture of impunity for crimes against journalists means that massacres like the one in Ampatuan can happen again,” he says. “Without justice, the bloodshed will continue.”

The NUJP played a key role in independent investigations and keeping a watch on government, also sponsoring family members of slain journalists to get to Manila for the trial.

Ruthless warlords

The Ampatuans were the warlords of Maguindanao and the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM).

“Even Andal Ampatuan Jr’s ruthlessness and sociopathic violence served a purpose,” admits Pamintuan. “Cops and soldiers who were assigned to the ARMM talk of the Islamic separatists being terrified of incurring the ire of Andal Jr because of his reported propensity to decapitate and mutilate anyone who crossed him.”

“There are other political warlords still out there – running their own fiefdoms like gangsters, naming streets and villages and government projects after their family members, freely using public money for private purposes and controlling every aspect of the local criminal justice system.”

Yes, a victory, but the fight to end impunity in the Philippines has just begun.

Professor David Robie, director of the Pacific Media Centre, was recently in Vinzons, Camarines Norte, Philippines, on a research sabbatical.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz