Women in hijab protest on Monday in Tehran on Monday. Images: Mashup of #دختران_خیابان_انقلاب from Omid Memarian’s Twitter post.

Women in hijab protest on Monday in Tehran on Monday. Images: Mashup of #دختران_خیابان_انقلاب from Omid Memarian’s Twitter post.

- Asia Pacific

- Asia Pacific Report

- Asia Report

- Enghelab Street

- Gender

- Global Voices

- hijab

- Human Rights

- Iran

- Islamic Revolution

- justice

- MIL-OSI

- Pacific Media Centre

- Pacific Region

- PMC Reportage

- Politics

- Protest

- Protests

- Reports

- Revolution Street

- Security

- theocracy

The ‘Girls of Revolution Street’ protest over Iran’s compulsory hijab laws

By Mahsa Alimardani of Global Voices

A spate of defiant Iranian women have taken to the streets of Tehran to protest against compulsory veiling.

Photos of their demonstrations have been widely circulated online under the hashtag #دختران_خیابان_انقلاب (translated to #Girls_of_Enghelab_Street). At least two women (of the six women appearing in the photos above) have been arrested.

The protests come on the heels of a similar move by an Iranian woman named Vida Movahed, who was arrested on December 27, 2017, after a photo of her silently waving her hijab above her unveiled head on Tehran’s Enghelab Street (“enghelab” means “revolution” in English) went viral.

Movahed was released from prison on January 27.

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the hijab became compulsory in various stages. The law was first introduced in March 1979; Iranian women, initially in support of the revolution against the monarchy, came out in the hundreds of thousands to rally against it.

The following year it became mandatory in government and public offices until 1983, when it became mandatory for all women.

The photo of Movahed’s hijab protest, standing atop an electrical box on Enghelab Street, went viral in the context of a wave of anti-government protests that swept the country beginning on December 28, 2017.

But Movahed’s defiance was in fact a mistaken icon for the nationwide protests. She had in fact performed the act as part of her own singular protest on December 27, 2017, for the White Wednesday campaign, in which Iranian women posted photos online of themselves wearing white while discarding their headscarves with the hashtag #whitewednesday. This was part of the My Stealthy Freedom movement founded by exiled journalist Masih Alinejad against mandatory hijab for women.

Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International started to advocate for Movahed’s release after it became known she was arrested shortly after her stand on Enghelab Street’s electrical post. By January 28, Nasrin Sotoudeh, a human rights lawyer inside of Iran, known (and often persecuted) for defending activists and opposition members, announced on her Facebook page that Movahed had been released the previous day:

Translation Original Quote:

The girl from revolution street has been freed.

When I returned to the prosecutor’s office to follow up on the case of the girl of Enghelab Street, the head of the prosecutor’s office told me she was released. I am happy to hear that she returned home yesterday. I hope this judicial case will not be used to harass her for taking up her rights. She has done nothing to justify prosecution. Please do not lay your hands on her [directed at authorities].

A day after the news of Movahed’s release, several women emulated Movahed, standing on electrical posts on Engheblab Street (top right in mash up image).

An informed source told the Campaign for Human Rights in Iran that Narges Hosseini, one of the protesters on Enghelab street, was was arrested on January 29. #girls_ofRevolution

Other women took similar stands, taking off their hijabs on different streets in Tehran, and in one instance in Isfahan, a city in central Iran, according to crowd source reports on Nariman Gharib’s www.enghelabgirls.com. However, the symbolism of the initial protests taking place on Enghelab Street, translated into “Revolution Street”, was not lost on those following the events.

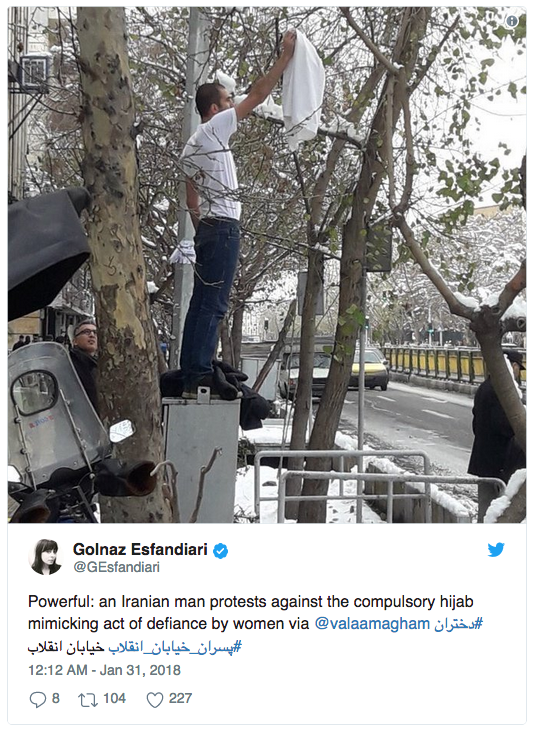

By the afternoon of January 30, several more women were spotted in Tehran taking off their veils, in addition to a man.

My Stealthy Freedom, which organised White Wednesday, the campaign that Movahed was participating in with her original act of defiance, was founded by Masih Alinejad. Alinejad and her movement are controversial in Iran, and sometimes subjected to smear campaigns by Iranian media, and associated with opposition activism inside of the country.

On the “My Stealthy Freedom” Facebook page, Alinejad welcomed those who had previously attacked her campaign but are now engaged in discussing and opposing compulsory hijab in light of the #girls_of_Enghelab_street:

Our #WhiteWednesdays campaign has been making an unstoppable impact and we are more than overjoyed. We are gratified to realize that the compulsory veil is no longer something than can be easily dismissed. It has always been an important issue as it relates to women’s freedom of choice. It is our most basic right. Our campaign has come a long way. We have also realized that people who attacked us yesterday are now onboard supporting our struggle. We warmly welcome them. We at my #StealthyFreedom do not judge people; our campaign is based on mutual respect.

One notable female voice on Iranian social media, Zahra Safyari, declared her support for the #Girls_of_Enghelab_Street and the right of Iranian women to choose to wear or not wear the hijab:

I am a chadori [wearer of a full-body-length cloak called a chador]. I have chosen for myself to be veiled, not for the force of my family, nor for my environment or conditions of my work. I am very happy with my choice but I am against mandatory hijab and I support the #Girls_of_Enghelab_Street. With religion and hijab there should be no force.

Safyari made a point to distance the protests from Masih Alinejad or any opposition movement aiming at overthrowing the Iranian establishment:

#Girls_of_Enghelab_Street are neither overthrowers, followers of Masih Alinejad, or the recipients of any money. They are the girls of this Iranian land who are following their basic rights.

Mahsa Alimardani is the Iran editor for Global Voices as well as an Iranian-Canadian internet researcher. Her focus is on the intersection of technology and human rights, especially as it pertains to freedom of expression and access to information inside Iran.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

]]>