Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Octavia Bryant, Doctoral Candidate, National School of Arts, Australian Catholic University

No doubt thanks to Donald Trump, Brexit, and a string of anti-establishment leaders and parties in Europe, Latin America and Asia, everyone seems to be talking about populism.

But populism is nothing new. It’s long accompanied democratic politics, and its activity and success has experienced peaks and troughs. Right now we’re in a bit of a heyday for populism, and this is impacting the nature of politics in general. So it’s important we know what it means and how to recognise it.

Even among academics, populism has been difficult to define. This is partly because it has manifested in different ways during different times. While currently its most well-known cases are right-wing parties, leaders and movements, it can also be left-wing.

There’s academic debate on how to categorise the concept: is it an ideology, a style, a discourse, or a strategy? But across these debates, researchers tend to agree populism has two core principles:

-

it must claim to speak on behalf of ordinary people

-

these ordinary people must stand in opposition to an elite establishment which stops them from fulfilling their political preferences.

These two core principles are combined in different ways with different populist parties, leaders and movements. For example, left-wing populists’ conceptions of “the people” and “the elite” generally coalesce around socioeconomic grievances, whereas right-wing populists’ conceptions of those groups generally tend to focus on socio-cultural issues such as immigration.

The ambiguity of the terms “the people” and “the elite” mean the core principles of people-centrism and anti-elitism can be used for very different ends.

Read more: Populism’s problems can be fixed by getting the public better-informed. And that’s actually possible

How can appealing to ordinary people be a bad thing?

Populism gets a bad name for a couple of reasons.

First, because many of the most prominent cases of populism have recently appeared on the radical right, it has often been conflated with authoritarianism and anti-immigration ideas. But these features are more to do with the ideology of the radical right than they are to do with populism itself.

Second, populists are disruptive. They position themselves as outsiders who are radically different and separate from the existing order. So they frequently advocate for a change to the status quo and may champion the need for urgent structural change, whether that is economic or cultural. They often do this by promoting a sense of crisis (whether true or not), and presenting themselves as having the solution to the crisis.

The leader of the Podemos party in Spain, who questioned capitalism in the wake of the Great Recession. Kiko Huesca/AAP

A current example of this process is Trump’s southern border wall, where he’s characterised the issue of illegal crossings on the southern border as a national emergency, despite, for example, more terrorist-related border crossings occurring on the northern, Canadian border and by air.

The fact populists often want to transform the status quo, ostensibly in the name of the people, means they can appear threatening to the democratic norms and societal customs many people value.

And the very construction of “the people” plays a large part in populists being perceived as “bad”, because it ostracises portions of society that don’t fit in with this group.

Read more: Perspectives on migrants distorted by politics of prejudice

What are some examples of populist leaders and policies?

The most famous contemporary example of a populist leader is the president of the United States, Donald Trump, and the renewed interest in populism is partly due to his 2016 electoral success. One way researchers measure populism, and consequently determine whether a leader or party is populist, is through measuring language.

Research has found Trump’s rhetoric during the campaign was highly populist. He targeted political elites, drawing on the core populist feature of anti-elitism and frequently used people-centric language, with a strong use of collective pronouns of “our” and “we”.

He combined this populist language with his radical right ideology, putting forward policies such as “America First” foreign policy, his proposed wall between the US and Mexico, and protectionist and anti-globalisation economic policies.

The combination of populism and such policies allowed him to draw a distinction between “the people” and those outside that group (Muslims, Mexicans), emphasising the superiority of the former.

These policies also allow for the critiquing of the elite establishment’s preference for globalisation, free trade and more liberal immigration policies. His use of the “drain the swamp” slogan – where he’s claiming he’ll rid Washington of elites who are out of touch with regular Americans – also reflects this.

Along with Trump, Brexit has also come to exemplify contemporary populism, because of its European Union-centred anti-elitism and the very nature of the referendum acting as an expression of “the people’s” will.

In South America, populism has been most associated with the left. The late Hugo Chavez, former president of Venezuela, was also highly populist in his rhetoric, and is perhaps the most famous example of a left-wing populist leader.

Chavez’s populism was centred around socioeconomic issues. Even while governing, he positioned himself as an anti-establishment politician, channelling the country’s oil revenues into social programs with the aim of distributing wealth among the Venezuelan people, relieving poverty and promoting food security.

Read more: Venezuela is fast becoming a ‘mafia state’: here’s what you need to know

The current Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and the Bolivian president, Evo Morales are also considered left-wing populist leaders.

But left-wing populism is not just confined to South America. In Europe, contemporary examples of left-wing populist parties include the Spanish Podemos and the Greek Syriza. These parties enjoyed success in the aftermath of the Great Recession. They questioned the legitimacy of unregulated capitalism and advocated structural economic changes to alleviate the consequences of the recession on their people.

It doesn’t look like populism is going anywhere. So it’s important to know how to recognise it, and to understand how its presence can shape our democracies, for better or worse.

– ref. What actually is populism? And why does it have a bad reputation? – http://theconversation.com/what-actually-is-populism-and-why-does-it-have-a-bad-reputation-109874

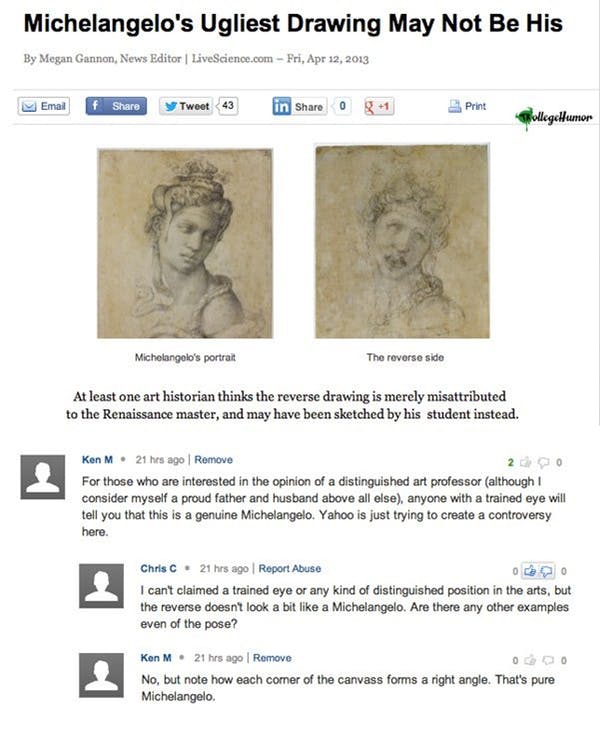

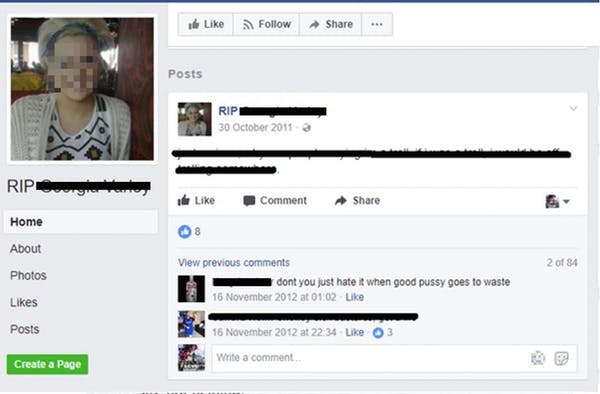

Without providing any definitions, we asked if this was an example of internet trolling. Of participants, 44 percent said yes, 41 percent said no and 15 percent were unsure.

Without providing any definitions, we asked if this was an example of internet trolling. Of participants, 44 percent said yes, 41 percent said no and 15 percent were unsure.

A word cloud representing how survey participants described trolling behaviours. Image: The Conversation

A word cloud representing how survey participants described trolling behaviours. Image: The Conversation