Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Silvia Griselda, PhD student, University of Melbourne

Last month, the Australian Academy of Science published a report showing the COVID-19 pandemic would disproportionately affect women in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) disciplines.

The report noted before COVID-19, around 7,500 women were employed in STEM research fields in Australia in 2017, compared to around 18,400 men. The authors wrote:

The pandemic appears to be compounding pre-existing gender disparity; women are under-represented across the STEM workforce, and weighted in roles that are typically less senior and less secure. Job loss at a greater rate than for men is now an immediate threat for many women in Australia’s STEM workforce, potentially reversing equity gains of recent years.

Women are less likely to enrol in science and maths degrees than men. In Australia, only 35% of STEM university degrees are awarded to women. This figure has been stable over the past five years.

Some research in the 1990s suggested girls don’t study maths and science because they might not do as well as boys. But recent research shows girls score similarly or slightly higher than boys in maths and science.

So why don’t they choose these careers as often as men?

Our recently published study found while women perform at the same or higher level in maths and science as men, their performance in the humanities is markedly better. This may be the reason they’re choosing not to pursue STEM careers.

Girls just as good at maths and science

We wanted to see if there were gender differences in school performance when it came to science and maths and whether these affected students’ university applications.

Our study used data of more than 70,000 secondary school students in Greece over ten years.

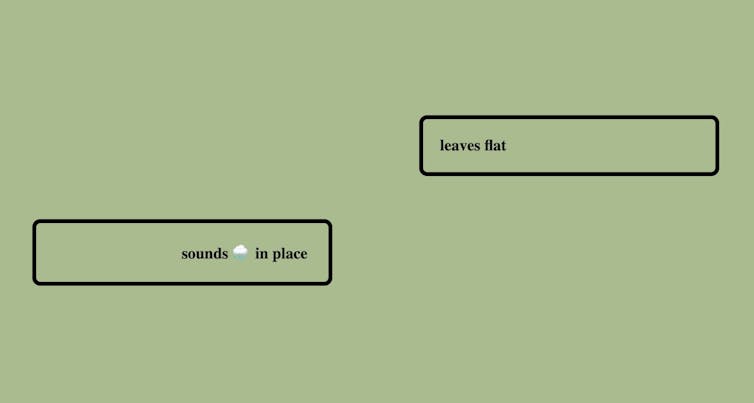

We found girls’ scores in maths and science were around 4% higher than boys. But their scores in humanities subjects were around 13% higher.

We also found girls were 34% less likely to chose a STEM-related specialisation in their last years of high school.

These findings can be translated to Australia. According to the latest results from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), girls in Australia perform on a similar level to boys in maths and science, but at a much higher level in reading.

The difference between girls’ and boys’ performance in reading is 6% in Australia and 9% in Greece.

But when it comes to maths and science, there is not much of a difference between girls’ and boys’ performance in either country.

Female comparative advantage in STEM

Our study showed students decided which fields they want to specialise in by comparing their academic strengths and weaknesses between subjects and with their classmates.

Using our data, we compared the students’ grades in STEM and humanities subjects. If a student had a higher grade in STEM than reading and writing subjects, we defined this student as having a STEM advantage. If this STEM advantage was greater than one of the students’ classmates, this student had STEM as an academic strength.

Because boys were generally better in science and maths than humanities, they had a higher STEM advantage. As girls were only slightly better in science and maths than humanities, their STEM advantage was lower than that of boys.

In our data, we considered pairs of girls with identical grades in STEM and humanities subjects at the beginning of secondary schools, who were randomly assigned to different classrooms. We then observed their enrolment decisions one to three years later.

For instance, two girls with a similar performance in STEM and humanities (with same STEM advantage) were assigned to different classrooms.

One girl was assigned to a classroom where her classmates had a high STEM advantage (higher scores in STEM than humanities). The other girl was assigned to a classroom where her classmates had a similar performance in STEM and humanities subject (no STEM advantage).

Our findings showed these two girls, on average, even if they had identical grades in STEM and humanities, chose different fields of study at the end of secondary school. The former (whose peers had a STEM advantage) was less likely to choose a STEM-related field.

Our study showed these two girls with identical performance ended up choosing a different educational career, based on which classmates they sat with.

This explained up to 12% of the gender gap in STEM enrolment in tertiary education.

We did the same for boys. Analysing pairs of boys with identical grades but different classmates, we did not observe any difference in their enrolment decisions.

What can be done?

Our research indicates girls are more influenced by their success relative to their peers, whereas this does not hold for boys.

Our findings are in line with previous research that suggests girls are more influenced by negative grades than boys, especially in STEM, when making decisions about their future.

Our research suggests the teacher has an important role to play in recognising and encouraging individual academic strengths, independently of classmates or gender.

Previous research has shown teacher gender stereotypes regarding girls’ ability in STEM negatively affects the way girls see themselves.

Teachers can and must foster confidence in girls when it comes to science and maths subjects, even if they may be better at reading and writing.

Maths and science studies lead to occupations such as engineering, physics, data science and computer programming, which are in great demand and generally pay a high salary. So turning away from STEM may have a long lasting impact on girls’ life earnings.

– ref. Girls score the same in maths and science as boys, but higher in arts – this may be why they are less likely to pick STEM careers – https://theconversation.com/girls-score-the-same-in-maths-and-science-as-boys-but-higher-in-arts-this-may-be-why-they-are-less-likely-to-pick-stem-careers-131563