Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety has recommended a levy to help fund aged care on a sustainable basis, and given the federal government two radically different options for running a reformed system.

Releasing the multi-volume report on Monday, Prime Minister Scott Morrison played down the prospect of the government adopting the levy proposal, which would go against its mantra of not raising tax.

The commission’s long-awaited final report, titled Care, Dignity and Respect, with 148 recommendations, complicates the government’s already massive task in trying to overhaul what is recognised to be an ill-functioning system.

In some areas it leaves questions rather than provides answers – such as how much extra money will be needed.

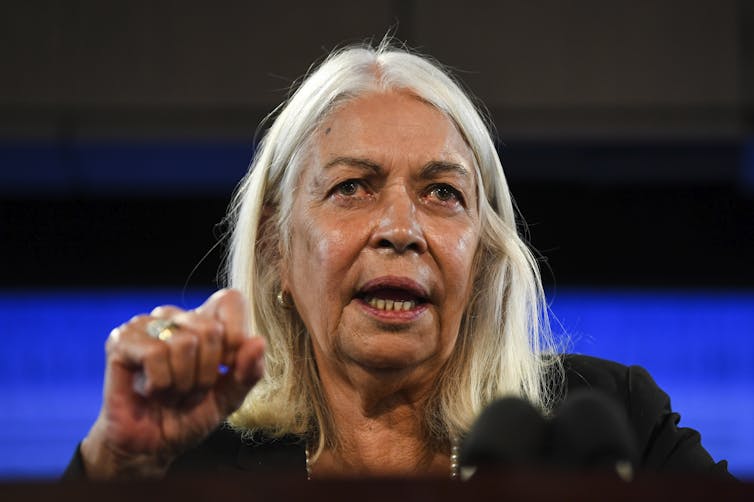

In other areas, it invites difficult choices between competing options presented by the two commissioners, Tony Pagone and Lynelle Briggs. They have split on the fundamental issue of how best to administer the system, as well as on the best way to improve the present inadequate regulatory arrangements.

Aged care is a federal government responsibility and the pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities in the system, with the majority of COVID-19 deaths occurring among aged care residents.

In an immediate response to the commission report, the government announced $452 million over the forward estimates, for limited initiatives in the areas of home care, residential aged care quality and safety, improving services in residential care; workforce growth, and governance measures.

The government’s main response is due at budget time. But much work will need to be done to craft a policy.

As expected, the commission is damning about the inadequacies in the present system.

“A profound shift is required in which the people receiving care are placed at the centre of a new aged care system. In the words of one commentator, aged care does not ‘need renovations, it needs a rebuild’,” Pagone writes in his preface.

The commissioners found a “gloomy picture” of systemic problems. Many of the sector’s people and institutions “are overwhelmed, underfunded or out of their depth”.

Briggs said that at least one in three people accessing residential care or home care services “have experienced substandard care”.

The commissioners jointly call a new Aged Care Act putting older people first, entitling them to high quality and safe care based on their needs.

While both stress the need for fundamental change, Pagone argues the system should be run by an independent commission, while Briggs favours strengthening the existing system of government administration.

As Pagone writes the decision will be up to the government and, “The adoption of one model over the other will have consequences for many … of the recommendations we make.”

It would be a huge step for the government to go down the road of an independent commission.

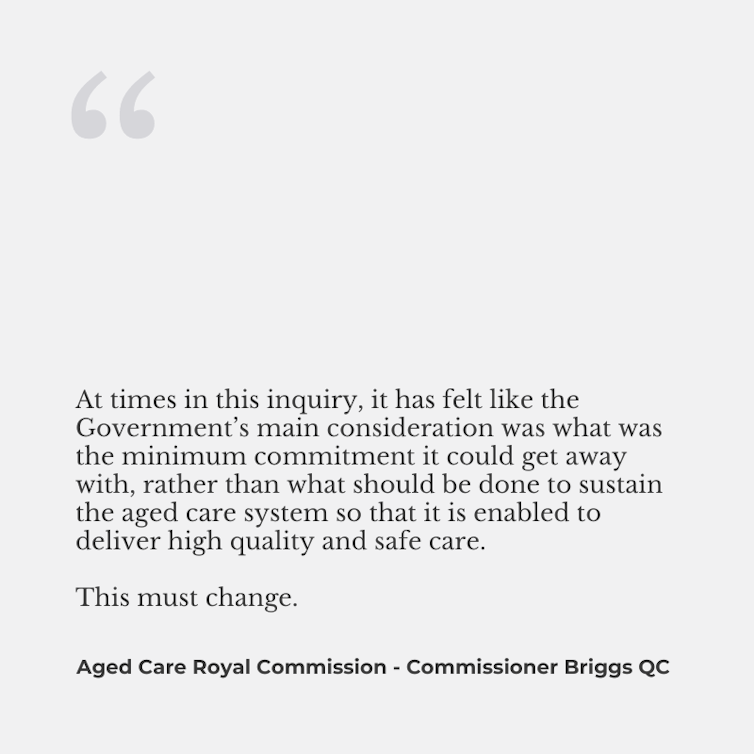

Briggs argues that establishing a new Australian Aged Care Commission would only delay important reforms. Such an arms-length body would also “weaken the direct accountability” of ministers for the quality of care.

Her alternative “Government Leadership” model would include greater independence in certain areas such as quality regulation and pricing, but maintain a strong federal government system leadership and stewardship role.

The commissioners propose tougher regulation of the system, with Pagone saying, “The move to ritualistic regulation was a natural consequence of the Government’s desire to restrain expenditure in aged care”.

They advocate different regulation arrangements. With Briggs supporting greater independence. They “both recommend stronger accountability through the establishment of an Inspector-General of Aged Care”.

The findings on home packages contradict the government’s claims about how well it has done in this area.

Pagone writes that people have waited about seven months for the lowest level of need and about 34 months for those with the highest need.

“Something has gone badly wrong when those most in need are forced to wait the longest for care,” he observes.

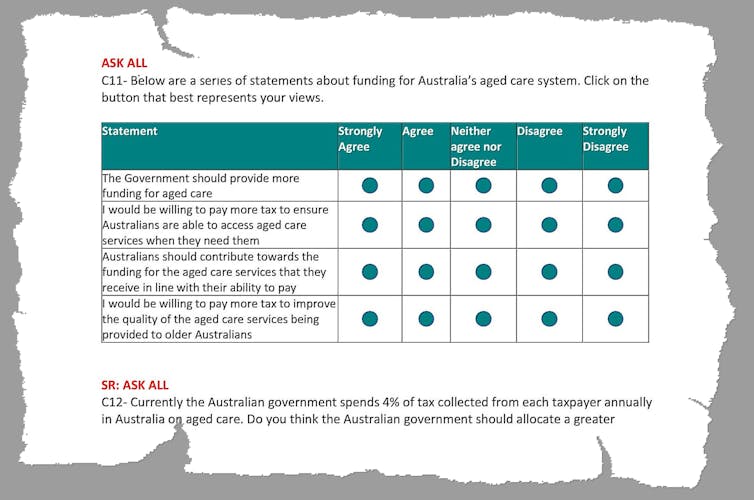

On funding, Pagone set out a proposal for an Aged Care levy, which would mean “each person will contribute toward the financing of the aged care system through their working life” according to their income. They would then be able to access it when they needed it, without a means test – as happens with Medicare.

Briggs puts forward an “aged care improvement levy” on personal taxable income of 1% to fund the increasing costs of aged care.

Asked about the levy Morrison said: “We’ll consider those things. You know our government’s disposition when it comes to increased levies and taxes. It is not something we lean to.”

He recalled that when he was treasurer, “I once sought to increase the Medicare levy by 0.5% to support the National Disability Insurance Scheme and I wasn’t supported in that by the Labor Party or the Greens for that matter.

“So that’s something that I’ve seen in other contexts that the parliament hasn’t supported before. So you’d forgive me for being a little wary at this point.”

The commission recommends an extensive shakeup of workforce arrangements, including registration of personal care workers, and professionalising the workforce through changes to education, training, wages, labour conditions and career progression.

– ref. View from The Hill: royal commission confronts Morrison government with call for aged care tax levy – https://theconversation.com/view-from-the-hill-royal-commission-confronts-morrison-government-with-call-for-aged-care-tax-levy-156207