I stayed away from the livestream that we in EMTV produced out of Port Moresby. I did watch parts of it. But it has been hard to watch a full session without becoming emotional and emotion is something that has been in abundance over the last 16 days.

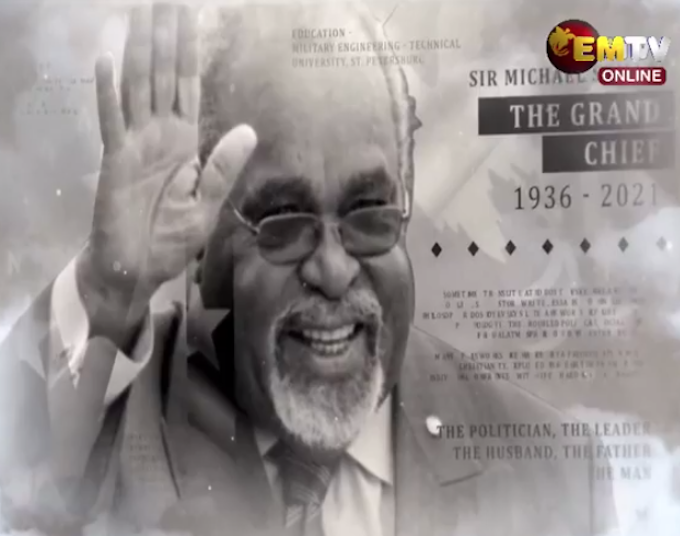

There are a thousand and one narratives embedded in the life of the man we call Michael Somare.

How could I do justice to all of it?

Do I write about the history? Do I write about the stories people are telling about him? Do I write about his band of brothers who helped him in the early years?

Sir Michael was, himself, a storyteller.

Narratives woven into relationships

He didn’t just tell stories with words. The narratives were woven into his existence and in the relationships he built throughout his life. From them, came the stories that have been given new life with his passing.

I went to speak to Sir Pita Lus, his closest friend and the man who, in Papua New Guinean terms, carried the spear ahead of the Chief. He encouraged Michael Somare to run for office.

He told me about the old days about how he had told his very reluctant friend that he would be Prime Minister. In Drekikir, Sir Pita Lus told his constituents that his friend Michael Somare would run for East Sepik Regional.

Sir Pita Lus and his relationship with Sir Michael is a chapter that hasn’t yet been written. It needs to be written. It is up to some young proud Papua New Guinean to write about this colorful old fella.

A chief builds alliances. But what are alliances? They are relationships. How are they transmitted? Through stories. Sir Michael built alliances from which stories were told.

When I went to the provincial haus krai in Wewak, there were huge piles of food. I have never seen so much food in my life. Island communities of Mushu, Kadowar and Wewak brought bananas, saksak and pigs in honor of the grand chief. They also have their stories to tell about Sir Michael.

The Mapriks came. Ambunti-Drekikir brought huge yams, pigs and two large crocodiles. The Morobeans, the Manus, the Tolais, West Sepik, the Centrals.

In Port Moresby, people came from the 22 provinces … From Bougainville, the Highlands, West Sepik and West Papua.

In Fiji, Prime Minister, Voreqe Bainimarama sent his condolences as he read a eulogy. In Vanuatu, Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) members held a special service in honour of Sir Michael. In Australia, parliamentarians stood in honour of Sir Michael Somare.

Followed to his resting place

Our people followed the Grand Chief to his resting place. The Madangs came on a boat. Others walked for days just to get to Wewak in time for the burial.

How did one man do that? How did he unite 800 nations? Because that is what we are. Each with our own language and our own system of government that existed for 60,000 years.

Here was a man who said, “this is how we should go now and we need to unite and move forward”.

In generations past, what have our people looked for? How is one deemed worthy of a chieftaincy?

I said to someone today that the value of a chief lies in his ability to fight for his people, to maintain peace and to unite everyone. In many of our cultures, a chief has to demonstrate a set of skills above and beyond the rest.

He must be willing to sacrifice his life and dedicate himself to that calling of leadership. He must have patience and the ability to forgive.

The value of the chief is seen both during his life and upon his passing when people come from all over to pay tribute.

For me, Sir Michael Somare, leaves wisdom and guidance – A part of it written into the Constitution and the National Goals and Directive Principles. For the other part, he showed us where to look. It is found in our languages and in the wisdom of our ancestors held by our elders.

Asia Pacific Report republishes articles from Lae-based Papua New Guinean television journalist Scott Waide’s blog, My Land, My Country, with permission.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz