Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jonti Horner, Professor (Astrophysics), University of Southern Queensland

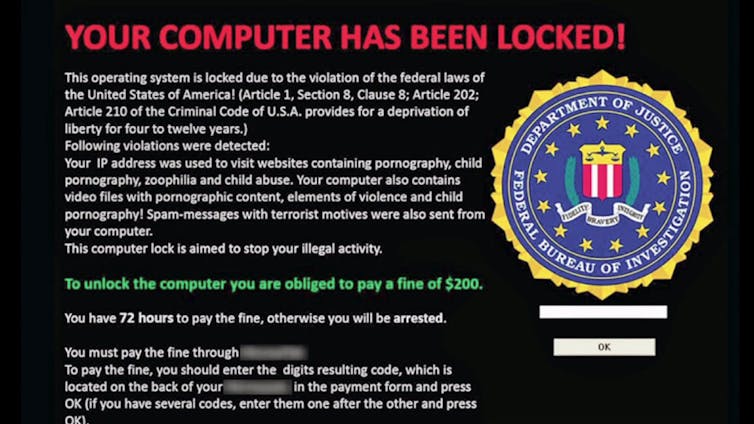

Shutterstock

I’m puzzled as to why the planets, stars and moons are all round (when) other large and small objects such as asteroids and meteorites are irregular shapes?

— Lionel Young, age 74, Launceston, Tasmania

This is a fantastic question Lionel, and a really good observation!

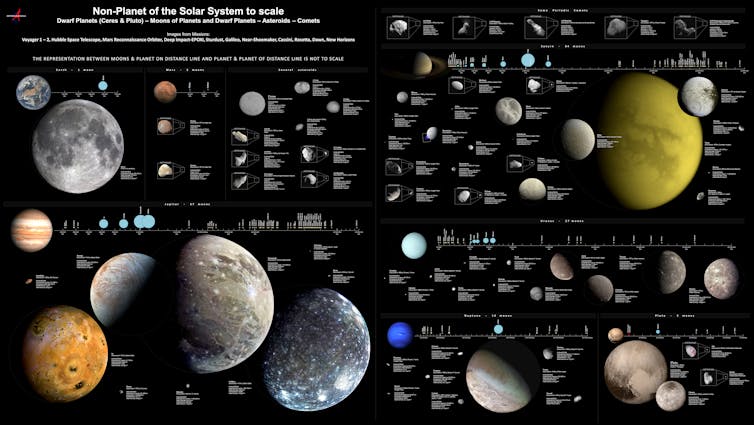

When we look out at the Solar System, we see objects of all sizes — from tiny grains of dust, to giant planets and the Sun. A common theme among those objects is the big ones are (more or less) round, while the small ones are irregular. But why?

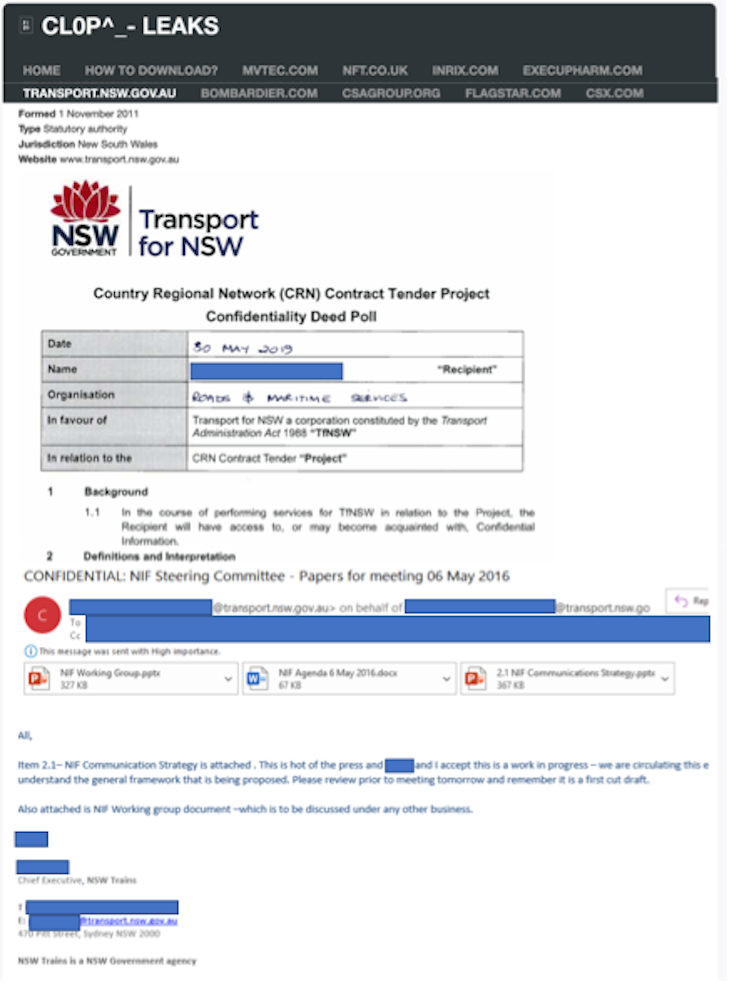

Wikipedia/Antonio Ciccolella

Gravity: the key to making big things round …

The answer to why the bigger objects are round boils down to the influence of gravity. An object’s gravitational pull will always point towards the centre of its mass. The bigger something is, the more massive it is, and the larger its gravitational pull.

For solid objects, that force is opposed by the strength of the object itself. For instance, the downward force you experience due to Earth’s gravity doesn’t pull you into the centre of the Earth. That’s because the ground pushes back up at you; it has too much strength to let you sink through it.

However, Earth’s strength has limits. Think of a great mountain, such as Mount Everest, getting larger and larger as the planet’s plates push together. As Everest gets taller, its weight increases to the point at which it begins to sink. The extra weight will push the mountain down into Earth’s mantle, limiting how tall it can become.

If Earth were made entirely from ocean, Mount Everest would just sink down all the way to Earth’s centre (displacing any water it passed through). Any areas where the water was unusually high would sink, pulled down by Earth’s gravity. Areas where the water was unusually low would be filled up by water displaced from elsewhere, with the result that this imaginary ocean Earth would become perfectly spherical.

But the thing is, gravity is actually surprisingly weak. An object must be really big before it can exert a strong enough gravitational pull to overcome the strength of the material from which it’s made. Smaller solid objects (metres or kilometres in diameter) therefore have gravitational pulls that are too weak to pull them into a spherical shape.

This, incidentally, is why you don’t have to worry about collapsing into a spherical shape under your own gravitational pull — your body is far too strong for the tiny gravitational pull it exerts to do that.

Read more:

Curious Kids: how and when did Mount Everest become the tallest mountain? And will it remain so?

Reaching hydrostatic equilibrium

When an object is big enough that gravity wins — overcoming the strength of the material from which the object is made — it will tend to pull all the object’s material into a spherical shape. Bits of the object that are too high will be pulled down, displacing material beneath them, which will cause areas that are too low to push outward.

When that spherical shape is reached, we say the object is in “hydrostatic equilibrium”. But how massive must an object be to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium? That depends on what it’s made of. An object made of just liquid water would manage it really easily, as it would essentially have no strength — as water’s molecules move around quite easily.

Meanwhile, an object made of of pure iron would need to be much more massive for its gravity to overcome the inherent strength of the iron. In the Solar System, the threshold diameter required for an icy object to become spherical is at least 400 kilometres — and for objects made primarily of stronger material, the threshold is even larger.

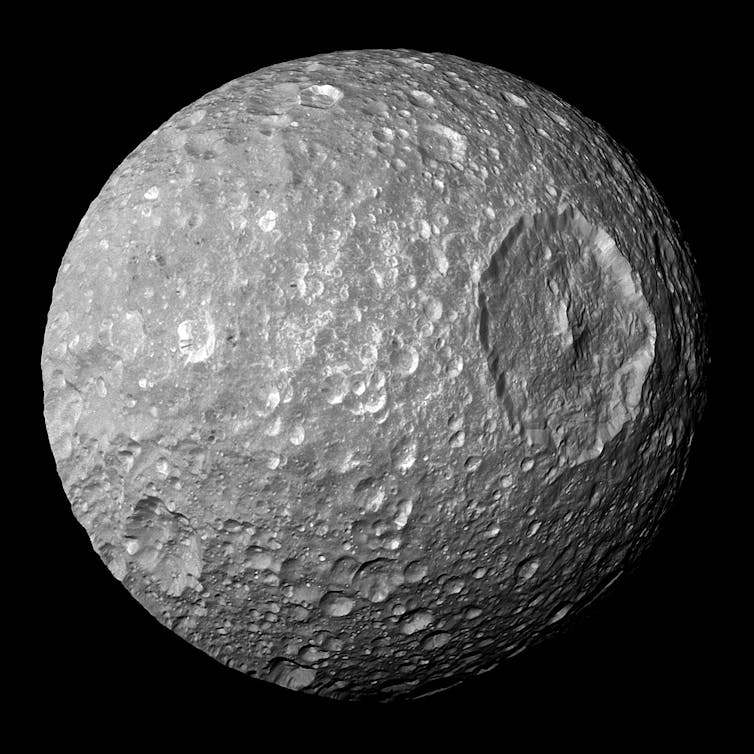

Saturn’s moon Mimas, which looks like the Death Star, is spherical and has a diameter of 396km. It’s currently the smallest object we know of that may meet the criterion.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

Constantly in motion

But things get more complicated when you think about the fact that all objects tend to spin or tumble through space. If an object is spinning, locations at its equator (the point halfway between the two poles) effectively feel a slightly reduced gravitational pull compared to locations near the pole.

Read more:

Even planets have their (size) limits

The result of this is the perfectly spherical shape you’d expect in hydrostatic equilibrium is shifted to what we call an “oblate spheroid” — where the object is wider at its equator than its poles. This is true for our spinning Earth, which has an equatorial diameter of 12,756km and a pole-to-pole diameter of 12,712km.

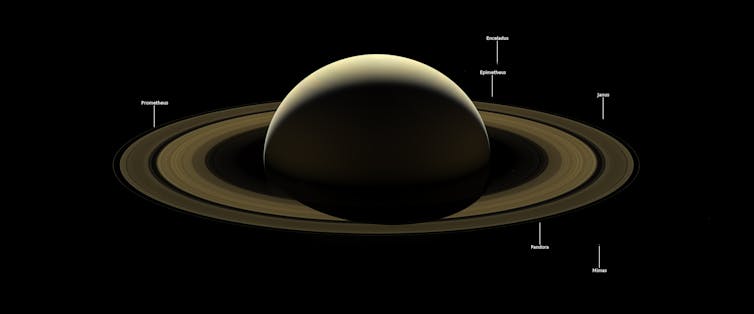

The faster an object in space spins, the more dramatic this effect is. Saturn, which is less dense than water, spins on its axis every ten and a half hours (compared with Earth’s slower 24-hour cycle). As a result, it is much less spherical than Earth.

Saturn’s equatorial diameter is just above 120,500km — while its polar diameter is just over 108,600km. That’s a difference of almost 12,000km!

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Some stars are even more extreme. The bright star Altair, visible in the northern sky from Australia in winter months, is one such oddity. It spins once every nine hours or so. That’s so fast that its equatorial diameter is 25% larger than the distance between its poles!

The short answer

The closer you look into a question like this, the more you learn. But to answer it simply, the reason big astronomical objects are spherical (or nearly spherical) is because they’re massive enough that their gravitational pull can overcome the strength of the material they’re made from.

This is an article from I’ve Always Wondered, a series where readers send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. Send your question to alwayswondered@theconversation.edu.au

![]()

Jonti Horner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. I’ve always wondered: why are the stars, planets and moons round, when comets and asteroids aren’t? – https://theconversation.com/ive-always-wondered-why-are-the-stars-planets-and-moons-round-when-comets-and-asteroids-arent-160541