Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Paul Strangio, Professor of Politics, Monash University

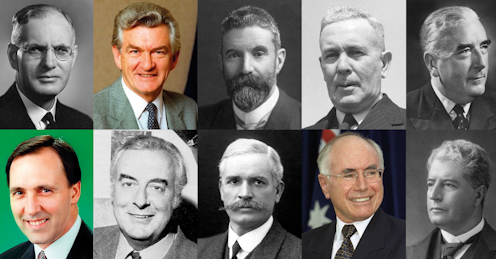

Public Domain except Hawke, Keating and Howard (Commonwealth of Australia CC-BY-SA)

Who have been Australia’s most accomplished prime ministers? Curiously, it’s a question that is seldom asked. We enthusiastically compile lists of the greatest films or sporting champions, but rarely do we apply the same energy to thinking about prime-ministerial virtuosity.

More common is the rush to condemn incumbents. For example, a recent venomous piece of commentary on Scott Morrison demanded to know: “Have we ever been led by a worse prime minister than this smirking vacuum?”

The problem with these hyperbolic attacks is that they lack context. How does Morrison’s leadership compare to his 29 predecessors? And, in any case, is it too early to properly judge his performance given his prime-ministerial project is incomplete?

Read more:

Lacking a script, individuals drove the evolution of prime ministerial power

What makes a great prime minister?

Evaluating leadership performance is replete with difficulties. This is despite the fact that, in democratic systems like ours, the mark of leadership achievement can appear deceptively simple.

On first consideration, longevity of office appeals as the sine qua non of successful political leadership. After all, winning government is the chief prize for a political leader, and retaining power, which is indicative of holding onto public support, affords the primary means by which to exercise influence.

Yet further reflection suggests survival alone is not a sufficient criterion of leadership success: it must also take account of what is accomplished with power. Indeed, should the legacy of a leader’s time in office be the paramount test of performance?

But then a new problem: how are we to construct meaningful and agreed upon measurements of the scale and quality of that legacy? Surely, for instance, the benchmark has to be more than the legislative productivity of a leader’s government. Yet once we endeavour to devise qualitative measurements that factor in the impact of the changes a leader has wrought, we inevitably run into disagreements about whether those changes were for good or bad.

One way of sidestepping the difficulties of evaluating political leadership is expert rankings. That is, ranking evaluations gained from people with professional knowledge, rather than surveys based on population sampling.

These have a storied history in the United States. Presidential rankings are not only conducted regularly but their results painstakingly analysed and hotly debated.

In parliamentary democracies such as Australia, leadership rankings have taken longer to catch on. But they have gained a foothold in recent decades. Most of them have been ad hoc surveys of a small number of public intellectuals and commentators initiated by broadsheet newspapers.

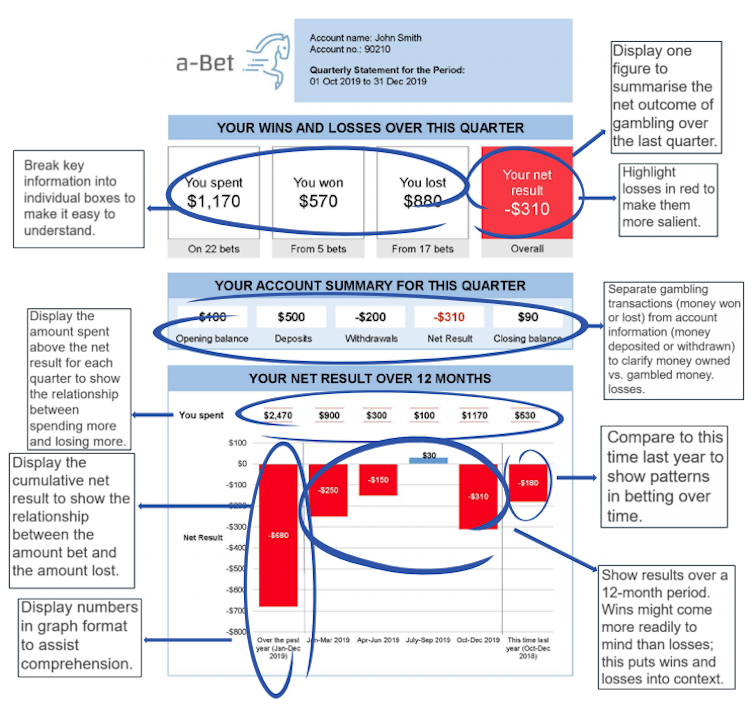

In 2010 and again in 2020, however, large-scale expert rankings surveys have been run out of Monash University. Sixty-six political scientists and political historians participated in last year’s survey. They were asked to rate the performance of all prime ministers, barring the incumbent (Morrison was not included as Julia Gillard was not included in the 2010 survey), and the three caretakers, Earle Page, Frank Forde and John McEwen, who briefly warmed the prime-ministerial seat following the death of an incumbent.

John Curtin, war-time PM, rated our greatest leader

The results of the 2010 and 2020 Monash surveys suggest there is a reasonable consensus about who have been our best prime ministers.

The top-rated national leader is Australia’s second world war prime minister and co-architect of its post-war reconstruction regime, John Curtin. Next comes Bob Hawke, whose governments modernised and internationalised Australia’s economy in the 1980s through market-based reforms cushioned by an overlay of social democratic values.

Third-ranked is Alfred Deakin, the Liberal Protectionist prime minister and the chief architect of the nation-building edifice laid down in the first Commonwealth decade. It included, among other things, tariff protection, an industrial arbitration system and the beginnings of a welfare state through provision of old age pensions.

AAP/AP

Ben Chifley, Curtin’s collaborator in the design of the post-war reconstruction Keynesian welfare state, is also in the top echelon. He is followed by Robert Menzies, the father of the modern Liberal Party and Australia’s longest-serving prime minister.

Others who make the top tier or are close to it are: Gough Whitlam, the reforming titan whose government dramatically modernised Australia in the early 1970s; Andrew Fisher, Australia’s first majority prime minister whose legacies included the establishment of the Commonwealth Bank and maternity allowances; and, in a delicious irony, the two great rivals, Paul Keating and John Howard. Keating is the big improver from the 2010 Monash ratings.

Longevity in office isn’t everything

The 2020 rankings also asked participants to rate prime ministers in nine performance areas. These were: effectively managing cabinet, maintaining support of party/coalition, demonstrating personal integrity, leaving a significant policy legacy, relationship with the electorate, communication effectiveness, nurturing national unity, defending and promoting Australia’s interests abroad, and being able to manage turbulent times.

Looking for correlations between performance in these areas and overall ratings it was evident that there was a close nexus between a high ranking and being scored strongly for policy legacy. The upper echelon prime ministers – Curtin, Hawke, Deakin, Chifley, Menzies, Keating, Whitlam, Fisher and Howard – were all in the top grouping for policy legacy.

Julia Gillard rounded out the policy legacy top ten, which seemed to go a long way to explaining her healthy rating in the upper middle tier of the former prime ministers.

Lukas Coch/AAP

It appears that in the minds of the participants the relationship with the electorate, while also important, ranks behind policy achievement in significance. Whitlam, Fisher and Keating were all outside the top ten for winning favour with the electorate, but are still highly ranked.

This is further reflected in the fact that, while Australia’s three most durable prime ministers – Menzies, Howard and Hawke – all make or are near the top tier, the next four longest-serving prime ministers and multiple election winners, Malcolm Fraser, Billy Hughes, Joseph Lyons and Stanley Bruce, do not.

In short, though longevity is important, what a prime minister does with office counts more to the experts. Strikingly, all of the top-ranked leaders were either the initiators or consolidators of major policy settlements.

A high score for nurturing national unity also strongly correlates with a favourable overall rating. Howard’s below-average result on that measure seems to disqualify him from pushing further up among the top-ranked prime ministers.

Conversely, the connection was weakest between a high ranking and the integrity performance benchmark. This does not mean the experts paid no heed to integrity. Rather, they had a generally favourable view of the collective integrity of our prime ministers, regarding them as a fundamentally upright bunch.

And who were the duds?

What about the prime ministerial dunces? There is not only a consensus about who have been our best prime ministers but also our worst.

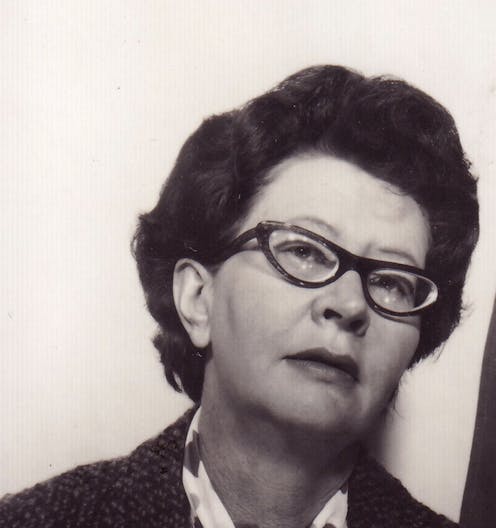

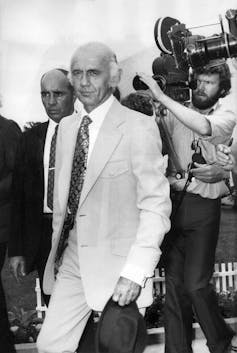

Museum of Australian Democracy

William McMahon, who was the nation’s leader in the dying days of the Liberal Party’s post-WWII ascendancy and was defeated by Whitlam at the December 1972 election, wins that dubious honour.

Yet the 2020 rankings suggest he now has a rival for that ignominious status: Tony Abbott. Indeed, despite squeaking ahead of McMahon on the overall performance question, Abbott exceeded him for the number of failure ratings: 44 to 41. Against the nine benchmarks, Abbott is ranked last for policy legacy and nurturing national unity. McMahon is bottom for six of the nine areas, among them integrity (part of his entrenched reputation is that of an inveterate schemer and leaker).

Read more:

Is the COVID vaccine rollout the greatest public policy failure in recent Australian history?

Notably, three of the four most recent prime ministers – Kevin Rudd, Malcolm Turnbull and Abbott – are situated towards or in the rear of the ratings pack. Together, they occupy the three bottom rungs for management of party/coalition. This suggests respondents hold them, rather than their colleagues, chiefly responsible for their depositions by party-room revolts.

The clear exception among the post-Howard prime ministers is Gillard. Though still only middle-ranked overall, she is by far the highest-rated leader among this ill-starred group.

Where will Morrison end up in the rankings? The short answer is that it is too early to tell since his is an unfinished story. The COVID-19 pandemic has ensured his incumbency will be a significant one, either for good or bad.

Yet the lack of much in the way of tangible policy achievements to this point does not bode well for his rating.

![]()

Paul Strangio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Who were Australia’s best prime ministers? We asked the experts – https://theconversation.com/who-were-australias-best-prime-ministers-we-asked-the-experts-165302