Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Agathe Tiana Randrianarisoa, PhD student and Senior Researcher, RMIT University

Darren Pateman/AAP

Imagine it’s summer in Australia and a bushfire is bearing down on your suburb. Are you the pragmatic type – you’ve swapped phone numbers with the neighbours, photocopied your ID and have your emergency plan at the ready? Or are you the sentimental type – you’ve backed up the family photos but forgotten to insure the house, or don’t have an evacuation plan for the cat?

Our research out today shows when it comes to getting ready for disasters, there are four types of people. And this matters, because good disaster preparedness doesn’t just help people during and immediately after a disaster – it can also mean a quicker recovery.

The research, commissioned by Australian Red Cross, examined the experiences of 165 people who lived through a disaster such as fire and flood between 2008 and 2019. We identified a number of steps people wished they’d taken to prepare for disaster, such as protecting sentimental items, planning where the family should meet if separated and better managing stress.

The Black Summer bushfires, this year’s New South Wales floods, the storms around Melbourne and even COVID-19 remind us how disasters can disrupt people’s lives. Hopefully, examining the hard-won lessons of those who’ve lived through the worst life can throw at us will help individuals and communities better prepare and recover from these events.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Our key findings

The survey questions focused on preparedness actions people took before a disaster, their experience of a disaster and recovery.

Participants were 18 years or older and had experienced a disaster between January 2008 and January 2019. This allowed time for people to experience the challenges and complexity of the recovery process.

Among our key findings were:

-

feeling prepared leads to a reduction in stress when dealing with the recovery process. And the less people are stressed, the better their recovery up to ten years after a disaster.

-

generally, the more people do to get prepared, the more they feel prepared. However, one in five respondents who reported not feeling prepared had undertaken actions that should have made them feel prepared. And 3% said they were prepared when they hadn’t undertaken any action, which mostly comes from the lack of knowledge of the most efficient preparedness actions.

-

the source of advice matters. More of those who received preparedness advice from Australian Red Cross – either directly or through its Get Ready app – had recovered. Those who had no preparedness training or received advice from family or friends were least likely to report having felt in control during the emergency.

Dominica Sanda/AAP

3 ways to prepare

Three distinct groups of preparation actions emerged, which we outline below.

Protect my personal matters:

- develop strategies to manage stress levels

- protect or back up items of sentimental value

- make copies and protect important documents such as identification papers, wills, financial documents

- make plans for reunification of family if separated during an emergency.

Build my readiness:

- identify sources of information to help prepare for and respond to an emergency

- find out what hazards might affect their home and plan for them

- use preparedness materials such as bushfire survival plans.

Be pragmatic:

- make a plan for pets/livestock/animals

- swap phone numbers with neighbours

- take out property insurance.

Those who had taken action to prepare for disaster were asked what other actions they wished they’d taken. The top answer was having copies of important documents, such as ID and financial papers, that are potentially complicated to replicate and may be needed during recovery.

The full range of answers is below:

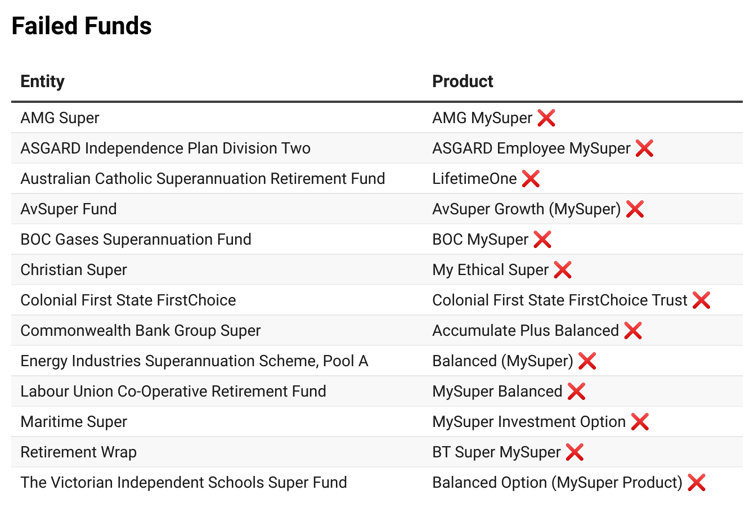

Which preparedness type are you?

Our research showed four types of persona emerged in terms of preparing for a disaster. Hopefully, identifying these groups means preparedness messaging can in future be customised, based on people’s characteristics.

Have a look at the graphic below – is there a type you identify with the most?

The Conversation/author provided data, CC BY-ND

Recovery is complex

Our survey asked if people felt they had recovered from the disaster. Importantly, we did not propose a standard definition of recovery, which allowed respondents to define their recovery in their own way. We then sought to determine how a person’s disaster preparation affected recovery.

Nearly 18% of respondents said they had not recovered at the time of the survey. Surprisingly, 86% of those said they took action to get prepared (compared to 76% of those who had recovered). But those who had not recovered were more likely to feel their preparation actions were not enough. Importantly, 86% also experienced high levels of stress during the recovery, compared to 60% who had already recovered at the time of the survey.

Interestingly, the proportion of respondents who found the recovery process slightly stressful, somewhat stressful or extremely stressful are comparable (15%, 16% and 16% respectively). However, four out of ten respondents reported high levels of stress during the recovery.

What’s more, a greater proportion of those who had not yet recovered required government assistance after the disaster (71%), relative to those who felt they had recovered (38%).

In the group of those not yet recovered, people earning less than A$52,000 a year were over-represented.

Read more:

COVID-19 revealed flaws in Australia’s food supply. It also gives us a chance to fix them

Dan Peled/AAP

Ready for anything

Our research shows being prepared can help reduce the long-term impacts of a disaster. The level of disaster preparedness in the Australian population is traditionally low, and so it’s important to demonstrate the benefits to ensure more people get ready for emergencies.

Preparedness programs should have a greater focus on preparing for the long-term impacts of a disaster. And these programs should differ based on people’s characteristics and they type of preparation support they need, particularly focusing on those who have less capacity to prepare and recover from the disruption of disaster.

This story is part of a series The Conversation is running on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation. Read the rest of the stories here.

![]()

Agathe Tiana Randrianarisoa works for Australian Red Cross. She also is a PhD student at RMIT University and DIAL (Dauphine University/IRD).

John Richardson works for Australian Red Cross. He is also an Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne School of Population and Global Health

– ref. When it comes to preparing for disaster there are 4 distinct types of people. Which one are you? – https://theconversation.com/when-it-comes-to-preparing-for-disaster-there-are-4-distinct-types-of-people-which-one-are-you-164169