Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Roderic Broadhurst, Chair Professor, Australian National University

Shutterstock

Child sexual abuse material is rampant online, despite considerable efforts by big tech companies and governments to curb it. And according to reports, it has only become more prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This material is largely hosted on the anonymous part of the internet — the “darknet” – where perpetrators can share it with little fear of prosecution. There are currently a few platforms offering anonymous internet access, including i2p, FreeNet and Tor.

Tor is by far the largest and presents the biggest conundrum. The open-source network and browser grants users anonymity by encrypting their information and letting them escape tracking by internet service providers.

Online privacy advocates including Edward Snowden have championed the benefits of such platforms, claiming they protect free speech, freedom of thought and civil rights. But they have a dark side, too.

Tor’s perverted underworld

The Tor Project was initially developed by the US Navy to protect online intelligence communications, before its code was publicly released in 2002. The Tor Project’s developers have acknowledged the potential to misuse the service which, when combined with technologies such as untraceable cryptocurrency, can help hide criminals.

Read more:

Explainer: what is the dark web?

Tor is an overlay network that exists “on top” of the internet and merges two technologies. The first is the onion service software. These are the websites, or “onion services”, hosted on the Tor network. These sites require an onion address and their servers’ physical locations are hidden from users.

The second is Tor’s privacy-maximising browser. It enables users to browse the internet anonymously by hiding their identity and location. While the Tor browser is needed to access onion services, it can also be used to browse the “surface” internet.

Accessing the Tor network is simple. And while search engine options are limited (there’s no Google), discovering onion services is simple, too. The BBC, New York Times, ProPublica, Facebook, the CIA and Pornhub all have a verified presence on Tor, to name a few.

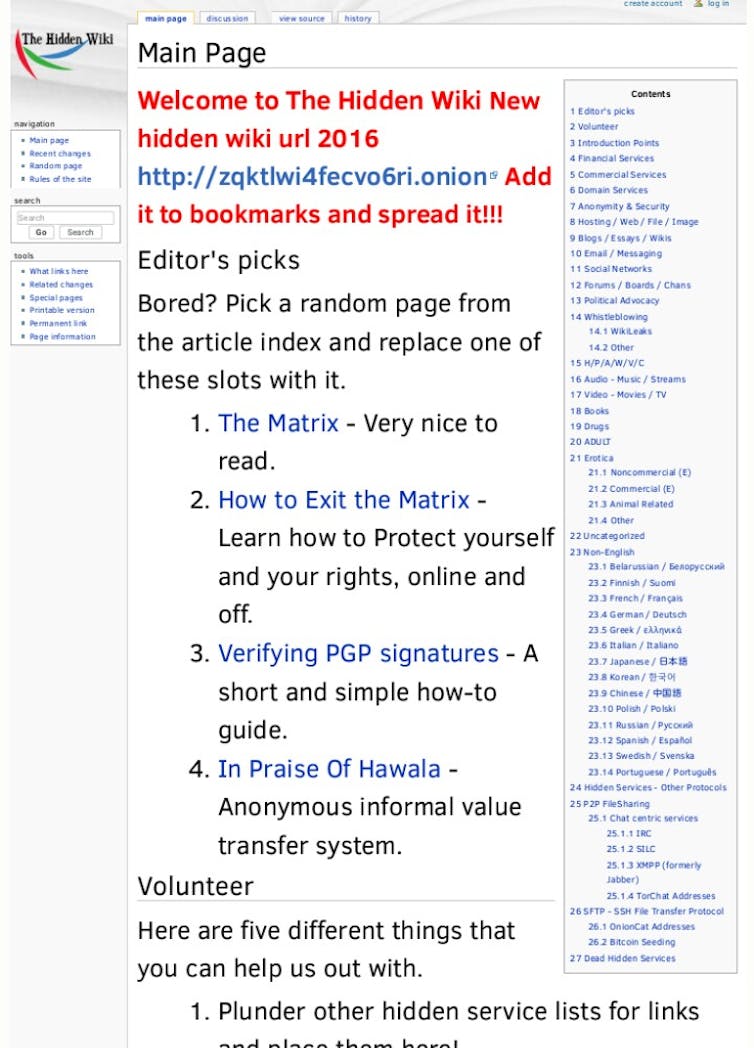

Service dictionaries such as “The Hidden Wiki” list addresses on the network, allowing users to discover other (often illicit) services.

Wikimedia Commons

Child sex abuse material and abuse porn is prevalent

The number of onion services active on the Tor network is unknown, although the Tor Project estimates about 170,000 active addresses. The architecture of the network allows partial monitoring of the network traffic and a summary of which services are visited. Among the visited services, child sex abuse material is common.

Of the estimated 2.6 million users that use the Tor network daily, one study reported only 2% (52,000) of users accessed onion services. This suggests most users access the network to retain their online privacy, rather than use anonymous onion services.

That said, the same study found from a single data capture that about 80% of traffic to onion services was directed to services which did offer illegal porn, abuse images and/or child sex abuse material.

Another study estimated 53.4% of the 170,000 or so active onion domains contained legal content, suggesting 46.6% of services had content which was either illegal, or in a grey area.

Although scams make up a significant proportion of these services, cryptocurrency services, drug deals, malware, weapons, stolen credentials, counterfeit products and child sex abuse material also feature in this dark part of the internet.

Only about 7.5% of the child sex abuse material on the Tor network is estimated to be sold for a profit. The majority of those involved aren’t in it for money, so most of this material is simply swapped. That said, some services have started charging fees for content.

Several high-profile onion services hosting child sex abuse material have been shut down following extensive cross-jurisdictional law enforcement operations, including The Love Zone website in 2014, PlaypEn in 2015 and Child’s Play in 2017.

A recent effort led by German police, and involving others including Australian Federal Police, Europol and the FBI, resulted in the shutdown of the illegal website [Boystown](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boystown_(website) in May.

But one of the largest child sex abuse material forums on the internet (not just Tor) has evaded law enforcement (and activist) takedown attempts for a decade. As of last month it had 508,721 registered users. And since 2013 it has hosted over a million pictures and videos of child sex abuse material and abuse porn.

The paedophile (eroticisation of pre-pubescent children), haebephile (pubescent children) and ephebophile (adolescents) communities are among the early adopters of anonymous discussion forums on Tor. Forum members distribute media, support each other and exchange tips to avoid police detection and scams targeting them.

The WeProtect Alliance’s 2019 Global Threat Assessment report estimated there were more than 2.88 million users on ten forums dedicated to paedophilia and paraphilia interests operating via onion services.

Countermeasures

There are huge challenges for law enforcement trying to prosecute those who produce and/or distribute child sex abuse material online. Such criminal activity typically falls across multiple jurisdictions, making detection and prosecution difficult.

Undercover operations and novel online investigative techniques are essential. One example is targeted “hacks” which offer law enforcement back-door access to sites or forums hosting child sex abuse material.

Such operations are facilitated by cybercrime and transnational organised crime treaties which address child sex abuse material and the trafficking of women and children.

Given the volatile nature of many onion services, a focus on onion directories and forums may help with harm reduction. Little is known about child sex abuse material forums on Tor, or the extent to which they influence onion services hosting this material.

Apart from coordinating to avoid detection, forum users can also share information about police activity, rate onion service vendors, share sites and expose scams targeting them.

The monitoring of forums by outsiders can lead to actionable interventions, such as the successful profiling of active offenders. Some agencies have explored using undercover law enforcement officers, civil society, or NGO experts (such as from the WeProtect Global Alliance or ECPAT International) to promote self-regulation within these groups.

While there is a lack of research on this, reformed or recovering offenders can also provide counsel to others. Some sub-forums seek to offer education, encourage treatment and reduce harm — usually by focusing on the legal and health issues associated with consuming child sex abuse material, and ways to control urges and avoid stimuli.

Other contraband services also play a role. For instance, onion services dedicated to drug, malware or other illicit trading usually ban child sex abuse material that creeps in.

Why does the Tor network allow such abhorrent material to remain, despite extensive opposition — sometimes even from those within these groups? Surely those representing Tor have read complaints in the media, if not survivor reports about child sex abuse material.

![]()

Roderic Broadhurst has received funding for a variety of research projects on cybercrime and darknet markets from the Australian Research Council, Australian Institute of Criminology, Korean institute of Criminology and, the Australian Criminology Research Council. Since April 2019 he has served on the Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation Research Working Group.

Matthew Ball does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How the world’s biggest dark web platform spreads millions of items of child sex abuse material — and why it’s hard to stop – https://theconversation.com/how-the-worlds-biggest-dark-web-platform-spreads-millions-of-items-of-child-sex-abuse-material-and-why-its-hard-to-stop-167107