Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Geoff Hanmer, Honorary Professional Fellow, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney

NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment

Universities have had few sources of capital funds since the Abbott government sidelined the Education Investment Fund in 2014. The loss of an estimated A$16 billion of income by 2023 due to the COVID-19 pandemic has simply added to this problem.

The City Deals process is one option, but for most universities it’s a poisoned chalice. A university will have to make a large financial contribution to the project and bears the risk of any cost overruns. These deals were conceived in the salad days prior to 2020 and now look decidedly wilted.

Read more:

Think big. Why the future of uni campuses lies beyond the CBD

How do these City Deals work?

The Perth City Deal, for example, includes a $695 million project for Edith Cowan University. With the Commonwealth providing $245 million and the state government $150 million, ECU must stump up $300 million and hand over its perfectly serviceable Mount Lawley campus to the state government. The upshot is that the university will spend much more than would be needed to upgrade that campus for the dubious benefit of moving it 6km to the CBD.

The Australian Department of Infrastructure describes City Deals as “a genuine partnership between the three levels of government and the community to work towards a shared vision for productive and liveable cities”. The Perth deal is clearly a boost for the CBD and the Western Australian construction industry. The benefits to teaching or research at ECU are less easy to identify.

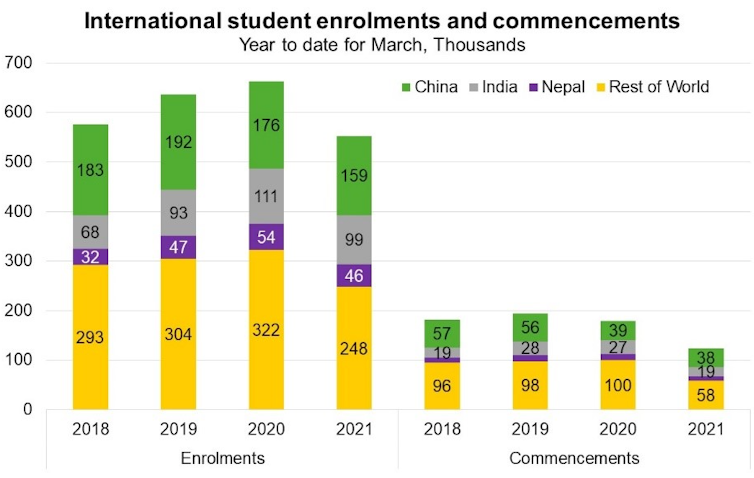

The Darwin City Deal commits Charles Darwin University (CDU) to a new campus in the Darwin CBD. CDU teaches 70% of its student load online, but it will end up with four campuses in Darwin with a combined capacity of well over 10,000 students to teach the 4,000 enrolled for on-campus study. The prospect of more students from China, which was a key component in planning for the project, has disappeared.

The deal required CDU to take out a $151.5 million loan from the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF). While the interest rate is low, the capital component must be paid back.

Again, this project is a boost for the Northern Territory construction industry, but it may well reduce CDU’s capacity to spend on teaching and research. As a result of longstanding financial pressures, CDU has already sacked 77 staff and scrapped courses.

Read more:

A fad, not a solution: ‘city deals’ are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Another option is to spend nothing on infrastructure. The University of Adelaide has announced a complete halt to such spending for the foreseeable future. It still plans to attract “top talent” with its ageing facilities. Quite how this will work is unexplained.

Developers are in it for the profits

Other universities have struck deals with developers. These can range from selling university assets and leasing them back, or signing up to a long-term lease on new purpose-built space using a special purpose vehicle (SPV), doing developments using university land, or other financial wizardry.

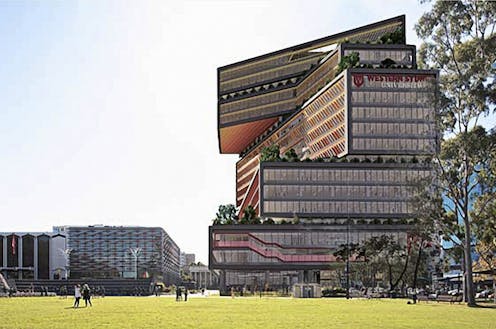

Charter Hall, a real estate investment company, has signed up Western Sydney University to several deals with a combined value of around a billion dollars. A new $350 million campus is being built in the CBD of Bankstown.

Charter Hall has openly said its aim is to create a new asset class in university buildings and campuses. This approach effectively privatises campus assets, nearly all of which were paid for with public money and charitable donations.

Western Sydney University is selling a newly built neighbourhood shopping centre and an adjoining residential development site. This was developed with Charter Hall on land controlled by the university, which says: “The Caddens Corner project is part of the Western Growth strategy, reshaping the University’s campus network, and allowing the University to maximise its investment in the core university activities of teaching, engagement and research.”

This is an interesting proposition, as teaching, engagement and research are all essentially operational, not capital, costs. In other words, the university is selling public assets to fund recurrent costs while planning to have 13 campuses to educate not many more students than Macquarie University, which has one.

Read more:

3 planning strategies for Western Sydney jobs, but do they add up?

In Melbourne, Swinburne University has put a seven-storey office building on Flinders Lane back on the market just one year after buying it for $44 million. In June, RMIT University in Melbourne brought forward plans to offload a 14-storey strata property on Bourke Street for more than $120 million and lease it back for five years.

A good time to borrow and build

Certainly, getting a developer to build a facility and lease it back to the university will reduce the need for capital. For similar reasons, a low-income household might choose a rental purchase arrangement to get a flat-screen TV. But like any rental purchase agreement, the short-term benefits pale in comparison to the long-term costs.

And universities are certainly about the long term. Four universities in Australia are more than 125 years old and they are youngsters compared to Harvard (385), Leiden (436), Oxford (925) or Bologna (933).

Read more:

A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

Another option for universities is to borrow money from a bank. If the universities can’t afford to do that, then they can’t afford to get developers to borrow money on their behalf and build them buildings while the developers also make a profit. There is no secret sauce and definitely no magic pudding.

Borrowing to fund the replacement or refurbishment of buildings at the end of their economic life is financially prudent providing benefits outweigh costs. University leaders might need to learn how to resist the temptation to make every building an “icon”, but capital investments to support teaching and research are rational and responsible. With interest rates as low as they will ever be and building costs a long way below the peak of the next cycle, now is an ideal time to build.

![]()

Geoff Hanmer is managing director of ARINA and a member of the Australian Institute of Architects, the Association of Consulting Architects, the Architectural Association and SAHANZ.

– ref. Why universities may come to regret the costs of City Deals and private sector ‘solutions’ – https://theconversation.com/why-universities-may-come-to-regret-the-costs-of-city-deals-and-private-sector-solutions-166670