Analysis by Keith Rankin,

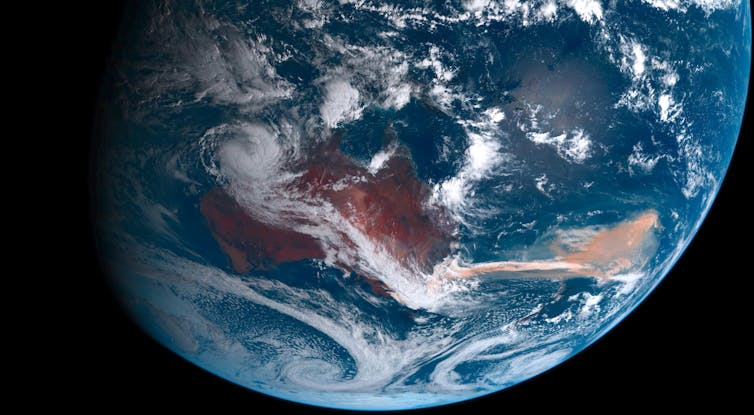

I have been watching the sudden rise to prominence of the word ‘Indo-Pacific’ these last couple of months. These last couple of days it may have been the most repeated word on Radio New Zealand.

According to Wikipedia today, Indo-Pacific is “biogeographic region”, although Wikipedia includes an outdated section on the geopolitical use of this conjoint word. Clearly, we can expect a major Wikipedia update this year.

When googling for a dictionary definition, I only got one, from Oxford “relating to the Indian Ocean and the adjacent parts of the Pacific”. Again, like Wikipedia the dictionaries are ‘behind the eightball’, as Americans might say, though the meaning of that expression is also not too clear. (I mean that the dictionaries are slow-moving; this month’s already ubiquitous meaning of ‘Indo-Pacific’ has outpaced the lexicographers.)

The best geopolitical definition that I have found is a list of 24 countries from CEO World: Australia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei, Cambodia, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Philippines Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor Leste, United States, Vietnam. These are presented, essentially, as a democratic bulwark to the south of China.

What matters much is which countries are excluded. First and foremost is of course China. Thus we can see that India-Pacific is a putative anti-China alliance. So this is not the ‘Asia-Pacific’ of APEC; that alliance emphasised economic cooperation. Economic cooperation is not what the Indo-Pacific is principally about; though economic cooperation (bullying?) to achieve geopolitical ends will almost certainly be high on the new agenda.

Also, with the emergence of AUKUS, we may understand the United Kingdom as an ‘honorary member’ of the Indo-Pacific, reflecting the former ‘British Empire’, and pointedly excluding European Union countries that have had not-to-long-ago imperial interests in this newly concocted geopolity.

Other countries not on the list are: Korea (North and South), Hong Kong, Macao, Pakistan, Canada, Russia. Also, it is important to note the absence of Latin America, East Africa, Polynesia, and parts of Melanesia. Re the latter two, imperial France remains a significant presence in both Polynesia and Melanesia.

As a geographic rather than a geopolitical region, the United States does not belong in the Indo-Pacific; the Wikipedia biogreographic region does not include anywhere in America or Northeast Asia, but does include Africa and Madagascar. Yet, as a new geopolitical entity, the United States has clearly placed itself at the centre, while otherwise excluding the Americas.

In addition to being an anti-China alliance, it can also be seen as an anti-Iranian alliance, with ‘Iran’ loosely defined to include Afghanistan and Iraq, and other ‘Middle-Eastern’ political entities subject to a degree of Iranian influence.

Based on the above list, South Korea and Pakistan can be seen as the key ‘neutral’ border countries between the Indo-Pacific and the new axes of enmity. While South Korea’s omission from the above list may be an oversight, we should see that the United States is slowly writing-off Pakistan; indeed, acquiescing in Narendra Modi’s accentuation of Hindu nationalism in India. Re Pakistan, watch that geopolitical space.

Hong Kong is now classed as a part of China.

Provocatively, the Indo-Pacific list includes Taiwan, Laos, and Myanmar. Realistically, Myanmar should not be there; it’s not a democracy. There are also issues with Vietnam’s credentials as a democracy. (And Bhutan, for that matter, strategically placed between China and India.)

Taiwan becomes the absolute frontline of what the new geopolitical discourse is about, and has significantly escalated as the likely flashpoint through which this new Cold War – between the Indo-Pacific (including United Kingdom) and whatever alliance China builds (including its entente with Russia). Beijing considers Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao as equal and intrinsic components of China.

The other little noticed potential flashpoint is Laos, which now has a relationship with China that has some parallels with the relationship between Cuba and United States before 1958. We may also note that post-Vietnam (embarrassment-distracting) United States foreign policy – especially the activities associated with the hapless though well-meaning Jimmy Carter, and his arch-cold-warrior Zbigniew Brzezinski) – substantially helped to set in play the geopolitical conflicts of the 1979 to 2021 era.

Aotearoa New Zealand is very much on the periphery of the dangerous new ‘Indo-Pacific’ bureaucratic amusement game – a game that is escalating in part to take attention away from the Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Syrian debacles. While we may hope that the new Hermit Kingdom – AoNZ – keeps out of this fray, we note Australia’s deep commitment to this new geopolitical posturing; and we note that our senior political leaders, bureaucrats, and foreign relations’ academics, have all embraced the new non-pacifist language of IndoPacificism.

Finally, we should note that one of the main features of the new alignment is its exclusion of the European Union. My gut feeling is that the gulf between Berlin/Paris and Washington/London will widen substantially this decade. And we should note that the United States is increasingly downplaying its former quasi-imperial role in the Americas, in favour of a new quasi-imperial alignment which refocuses on Southeast Asia as well as its Australian and British ‘deputy-sheriffs’.

Where does all this leave Canada? On Monday, Canada goes to the polls in what has been described to me as a “vanity election”. Further, the United States maintains a closed border to Canada, despite Canada having opened its border to the United States. Just as the New Zealand Australia relationship is being sorely tested, so is that between Canada and the United States. Another space to watch.

————-

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.