Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Lucinda McKnight, Senior Lecturer in Pedagogy and Curriculum, Deakin University

The recently released report of the review into initial teacher education recommends universities use randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to find evidence for effective methods of educating teachers. It says:

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), the gold standard in empirical research, are

rarely used in evaluating the impact of initial teacher education (ITE) programs. Higher education providers are encouraged to conduct RCTs to inform evidence-based

teaching practice.

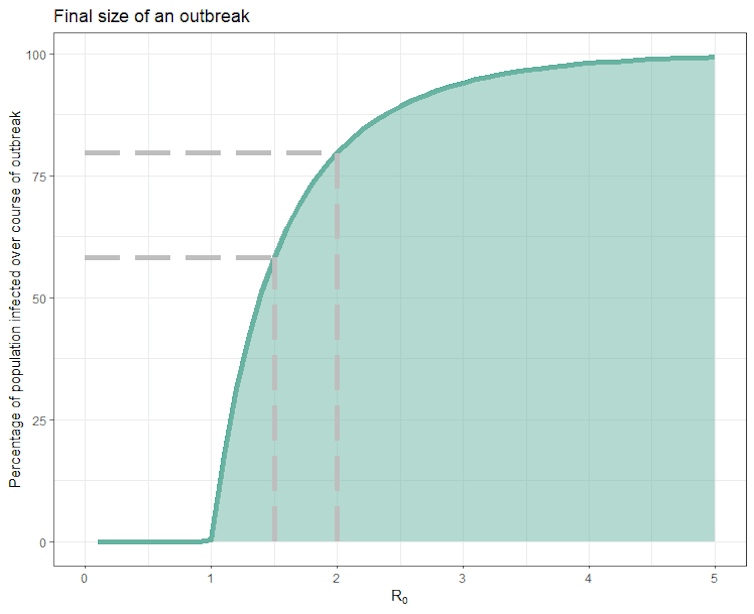

Randomised controlled trials are indeed the “gold standard” for specific kinds of medical research. They are the best way to compare a new treatment to either a standard treatment or no treatment at all.

In such a study, participants are randomly allocated to either the new or standard (control) treatments using the computer equivalent of tossing a coin. This process is known as randomisation. When the results are compared between the two groups, randomisation ensures an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect.

But it is naive to transpose the gold standard for specific kinds of research in medicine onto an entirely different discipline, such as teaching.

In educational research, a study might ask what challenges Indigenous Australians face in becoming teachers. This might involve a yarning or narrative inquiry approach, in which preservice teachers and researchers share their stories for in-depth collaborative analysis.

Another study might wonder why preservice teachers identify one placement school as having an especially supportive learning culture. This invites a case study of the school involving the principal, teachers, students and community, to understand the complex dimensions of this context.

Neither of these projects is less valid or important than those suited for randomised controlled trials. And creating a hierarchy of importance can mean research funding is directed away from any study that doesn’t use a randomised controlled method.

Where randomised trials are beneficial

A study that attempts to establish cause (usually an intervention) and effect (a desired improvement) might involve a randomised controlled trial. For instance, a study might want to examine the impact of a new program for teacher education.

One such study is a trial conducted in NSW in 2014-15 on the effectiveness of Quality Teaching Rounds – a specific approach to teacher professional learning in schools. Researchers wanted to know if this approach improved teaching. Teachers were randomly allocated to one of two intervention groups that would undertake the quality teacher rounds, or to a control group.

Read more:

Randomised control trials: what makes them the gold standard in medical research?

Researchers observed and assessed the teaching of all participants. The researchers were “blinded”, meaning they did not know whether they were assessing teachers in the intervention or control group. The trial found Quality Teaching Rounds made a statistically significant improvement in the quality of teaching in the intervention groups.

Other educational research is just as valid

In a different kind of study, researchers wanted to gain insight into the perspective of teachers themselves on how they learn at their workplace. A randomised controlled trial would not be able to achieve this aim.

Instead, researchers conducted in-depth interviews with four teachers they selected from a larger group. They encouraged teachers to talk freely about their learning goals, then coded and categorised their transcribed responses. Through this, researchers identified ways teachers feel they learn best: through reading, experience, reflection and collaboration.

Read more:

We have the evidence for what works in schools, but that doesn’t mean everyone uses it

Another example of important educational research that can’t be done through randomised controlled trials is action research, where teachers try a new classroom idea, reflect critically on the process and modify their approach – in an ongoing cycle. In one such project two teachers are investigating the effect of interdisciplinary team teaching on student and teacher learning. Teacher researchers also reflect on feedback from other colleagues and students.

This kind of research is identified as empowering for teachers and offers scope for them to create their own projects. Randomised controlled trials, in contrast, are complex for teachers to establish and run reliably.

The limitations of randomised trials

The newly established Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO) has published some extraordinary guidelines advising teachers to conduct randomised controlled trials in their classrooms.

The organisation suggests individual teachers should flip a coin to decide how they will teach, or split their class randomly into two, and teach one half one way and the other half another. However, this is methodologically unsound and impractical in a single class. The person deciding who gets the intervention should not be the person delivering the intervention or assessing the outcome. Otherwise bias is inevitable.

AERO’s advice demonstrates ignorance not only of randomised controlled trials, but of teacher workloads, by expecting teachers to teach in two ways at once.

Even in medicine (where they originated), randomised controlled trials cannot answer all questions. They cannot, for example, determine people’s attitudes, biases and commitments to certain issues. Medical researchers also use the various approaches described above.

Read more:

In defence of observational science: randomised experiments aren’t the only way to the truth

Research shows one disadvantage of randomised controlled trials in education is that the interventions they assess are not likely to have the same effect across all contexts and groups of students. They require additional process evaluations.

Another disadvantage is randomised controlled trials tend to be externally designed and academically-run, rather than teacher-led. Few teachers are experts in medical-style research. This positions teachers in a subservient way, in their own profession. Our research suggests it is just as important to understand “what is going on”, as it is to try to prove “what works”.

Privileging scientific measurement over participants’ voices

The ideal way to find answers to questions in education is to conduct quantitative (numbers-based) and qualitative (people-based) research in parallel. This would answer complementary questions.

But privileging one kind of research over all others demonstrates a lack of understanding of the nature of research. It suggests a bullying preoccupation with scientific measurement over research that privileges participants’ voices, especially in a feminised profession.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Scientific measurement won’t answer all questions in education. We need teacher and student voices, too – https://theconversation.com/scientific-measurement-wont-answer-all-questions-in-education-we-need-teacher-and-student-voices-too-178167