Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Noel Castree, Professor of Society & Environment, University of Technology Sydney

“Crisis” is an incredibly potent word, so it’s interesting to witness the way the phrase “climate crisis” has become part of the lingua franca.

Once associated only with a few “outspoken” scientists and activists, the phrase has now gone mainstream.

But what do people understand by the term “climate crisis”? And why does it matter?

The mainstreaming of crisis-talk

It’s not only activists or scientists sounding the alarm.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres now routinely employs dramatic phrases like “digging our own graves” when discussing climate. Bill Gates advises us to avoid “climate disaster”.

This linguistic mainstreaming marks redrawn battle lines in the “climate wars”.

Denialism is in retreat. The climate change debate now is about what is to be done and by whom?

Scientists, using the full authority of their profession, have been key to changing the discourse. The lead authors of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports now pull no punches, talking openly about mass starvation, extinctions and disasters.

Read more:

An official welcome to the Anthropocene epoch – but who gets to decide it’s here?

These public figures clearly hope to jolt citizens, businesses and governments into radical climate action.

But for many ordinary folks, climate change can seem remote from everyday life. It’s not a “crisis” in the immediate way the pandemic has been.

Of course, many believe climate experts have understated the problem for too long.

And yet the new ubiquity of siren terms like climate “crisis”, “emergency”, “disaster”, “breakdown” and “calamity” does not guarantee any shared, let alone credible, understanding of their possible meaning.

This matters because such terms tend to polarise.

Few now doubt the reality of climate change. But how we describe its implications can easily repeat earlier stand-offs between “believers” and “sceptics”; “realists’ and “scare-mongerers”. The result is yet more political inertia and gridlock.

We will need to do better.

Four ideas for a new way forward

Terms like “climate crisis” are here to stay. But scientists, teachers and politicians need to be savvy. A keen awareness of what other people may think when they hear us shout “crisis!” can lead to better communication.

Here are four ideas to keep in mind.

1. We must challenge dystopian and salvation narratives

A crisis is when things fall apart. We see news reports of crises daily – floods in Pakistan, economic collapse in Sri Lanka, famine in parts of Africa.

But “climate crisis” signifies something that feels beyond the range of ordinary experience, especially to the wealthy. People quickly reach for culturally available ideas to fill the vacuum.

One is the notion of an all-encompassing societal break down, where only a few survive. Cormac McCarthy’s bleak book The Road is one example.

Central to many apocalyptic narratives is the idea technology and a few brave people (usually men) can save the day in the nick of time, as in films like Interstellar.

The problem, of course, is these (often fanciful) depictions aren’t suitable ways to interpret what climate scientists have been warning people about. The world is far more complicated.

2. We must bring the climate crisis home and make it present now

Even if they’re willing to acknowledge it as a looming crisis, many think climate change impacts will be predominantly felt elsewhere or in the distant future.

The disappearance of Tuvalu as sea levels rise is an existential crisis for its citizens but may seem a remote, albeit tragic, problem to people in Chicago, Oslo or Cape Town.

But the recent floods in eastern Australia and the heatwave in Europe allow a powerful point to be made: no place is immune from extreme weather as the planet heats up.

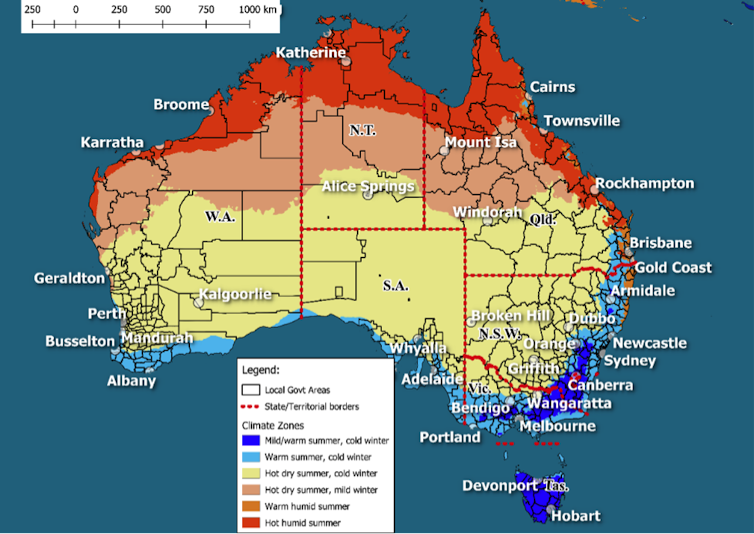

There won’t be a one-size-fits-all global climate crisis as per many Hollywood movies. Instead, people must understand global warming will trigger myriad local-to-regional scale crises.

Many will be on the doorstep, many will last for years or decades. Most will be made worse if we don’t act now. Getting people to understand this is crucial.

3. We must explain: a crisis in relation to what?

The climate wars showed us value disputes get transposed into arguments about scientific evidence and its interpretation.

A crisis occurs when events are judged in light of certain values, such as people’s right to adequate food, healthcare and shelter.

Pronouncements of crisis need to explain the values that underpin judgements about unacceptable risk, harm and loss.

Historians, philosophers, legal scholars and others help us to think clearly about our values and what exactly we mean when we say “crisis”.

4. We must appreciate other crises and challenges matter more to many people

Some are tempted to occupy the moral high ground and imply the climate crisis is so grand as to eclipse all others. This is understandable but imprudent.

It’s important to respect other perspectives and negotiate a way forward. Consider, for example, the way author Bjørn Lomborg has questioned the climate emergency by arguing it’s not the main threat.

Lomborg was widely pilloried. But his arguments resonated with many. We may disagree with him, but his views are not irrational.

We must seek to understand how and why this kind of argument makes sense to so many people.

Words matter. It’s vital terms like “crisis” and “calamity” don’t become rhetorical devices devoid of real content as we argue about what climate action to take.

![]()

Noel Castree does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The climate crisis is real – but overusing terms like ‘crisis’ and ’emergency’ comes with risk – https://theconversation.com/the-climate-crisis-is-real-but-overusing-terms-like-crisis-and-emergency-comes-with-risk-188750