Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mianna Lotz, Associate Professor in Philosophy & Chair of Faculty of Arts Human Research Ethics Committee, Macquarie University

The opportunity to conceive, carry and give birth to a biologically related child is a deep desire for many women and their partners. Since the introduction of IVF in 1978, many people in countries such as Australia have accessed support and resources to help realise their reproductive goals.

For some women, the lack a functioning uterus has kept that opportunity out of reach. This includes those with a congenital condition such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, and those who had a hysterectomy for medical reasons.

For these women, the only options for parenthood have been surrogacy or adoption. Access to both is often difficult.

Uterus transplants are changing that. From next year, uterus transplants are being trialled in Australia. However, there are risks involved and ethical concerns which must addressed before it can become mainstream clinical treatment.

How does the process work?

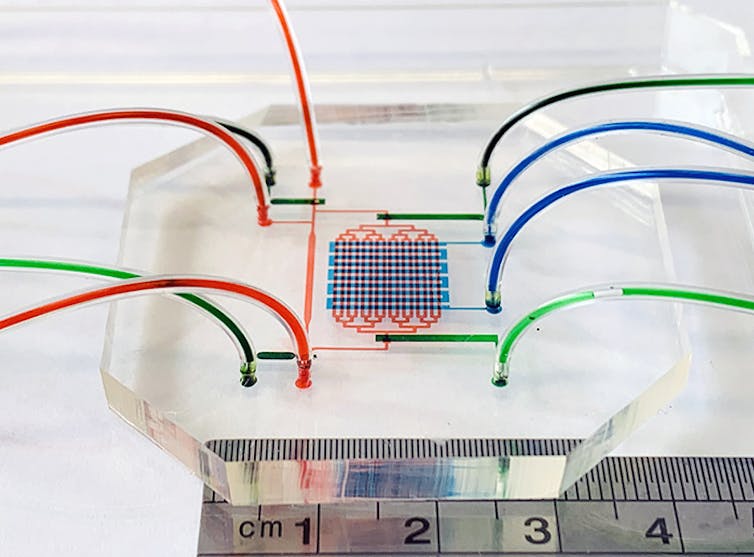

Uterus transplantation is a set of medical procedures in which a donated uterus is surgically removed from a suitable donor and transplanted into an eligible recipient.

Hormones are used to stimulate menstruation in the recipient, and once the uterus is functioning normally, an IVF-created embryo is transferred into the woman’s uterus.

Following successful implantation and healthy development, the baby is delivered via caesarean section. This is because a uterus transplant pregnancy is regarded as high risk, and the woman may not be able to feel contractions. Women with the congenital absence of a uterus will not be able to deliver vaginally.

Read more:

Explainer: what are womb transplants and who could they help?

As with all transplants, the uterus recipient is prescribed immunosuppression medication to prevent rejection of the donor organ. These drugs are administered at levels deemed safe for the developing foetus. Close monitoring continues throughout the pregnancy to ensure the safety of both woman and foetus.

Immunosuppression continues until the delivery of up to two healthy babies or five years after the transplant, whichever is first.

Omurden Cengiz/Unsplash

The uterus is then surgically removed via hysterectomy, enabling immunosuppression – which carries risks and side-effects – to be ceased. Risks from immunosuppression include infection, reduced blood cell count, heart disease and suppression of bone marrow growth. And these risks increase with time.

Uterus transplantation is an “ephemeral” transplant: a non-life-saving temporary transplant, aimed solely at enabling reproduction. These features make it medically and ethically distinct from other transplants.

When did uterus transplants start?

Scientists started developing uterus transplantation in animals in the 1970s. The first attempts in humans occurred in 2000 (Saudi Arabia) and 2011 (Turkey), both of which failed.

After 14 years of research, Professor Mats Brannstrom and his team at Sweden’s Sahlgrenska University Hospital started the world’s first human trials in 2013. In 2014, the first healthy baby was born.

With more than 25 countries now performing or planning uterus transplants, it is estimated that at least 80 procedures have been performed, resulting in more than 40 healthy live births. While not all transplants are successful, the live birth rate from a uterus that is functioning successfully after transplantation is estimated at over 80%.

In Australia, two trials have been approved and plan to start within the next 12-18 months.

Who donates?

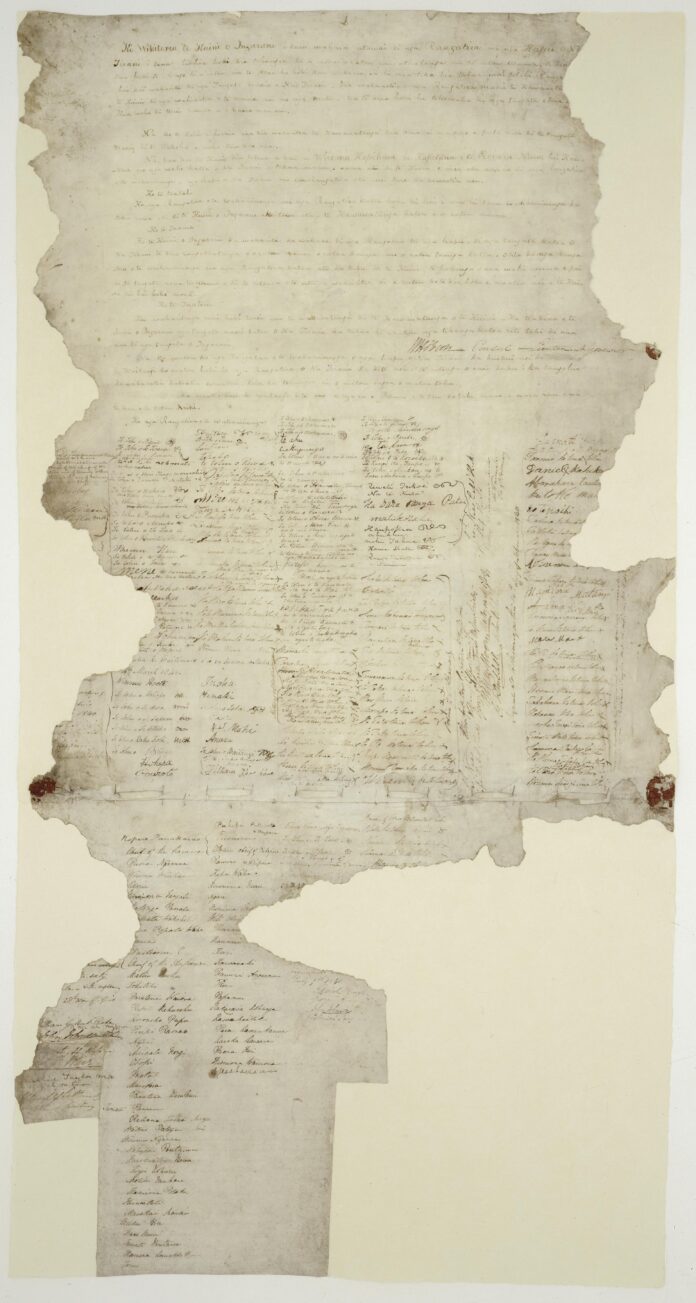

Most uterus transplants so far have used altruistic living donors, typically a mother donating to her daughter or an aunt to her niece.

Bence Halmosi/Unsplash

But cases using uteruses from deceased donors have also been successful, with at least four healthy live births reported.

Uteruses from deceased donors are mostly provided through standard family consent methods for medical research. But in future they could be provided through organ donor registration processes modified to include the uterus.

Currently, only pre-menopausal women can be uterus donors, and living donors need to have had a successful pregnancy to be eligible to donate. But this may not need to be a requirement for deceased donors, potentially enabling younger donors and increasing the availability of uteruses for transplantation.

Of the two approved Australian trials, only one (led by Royal Hospital for Women, for which I provide independent ethical advice) will conduct both living and deceased donor uterus transplantation. The other (through Royal Prince Alfred hospital) will trial only living donor transplantation.

Participation in these uterus transplant trials will remain limited while uterus transplantation is still in the research phase, and will depend on the availability of funding.

What are the risks of living donation?

For recipients, the main surgical risks are organ rejection, infection, and blood clots or thrombosis, as well as risks arising from the surgery duration (average 5 hours) such as blood clots (including in the lung) and from immunosuppression.

While challenging, these risks have been minimised through close monitoring and early intervention using blood thinners and encouraging recipients to move around soon after surgery.

For living donors, physical risks arise from surgery duration (6-11 hours) and operative and postoperative complications, the most common being urinary tract injury and infection.

There are also ethical and psychological risks. These include the possibility of a potential donor feeling pressured to donate to a family member, and experiencing guilt and failure if the transplant is not successful or results in adverse outcomes.

These risks may be reduced with appropriate counselling and support. But as with all altruistic organ donation, they cannot be entirely eliminated.

What about deceased donation?

Deceased donor transplantation also carries risks but involves less surgical time than living donor transplantation (typically 1-2 hours) and therefore less demand on medical resources and personnel.

Deceased donor transplantation may be less ethically fraught. There is no prospect of pressure, guilt or surgical risk to the deceased donor, who must have been declared brain dead and be suitable for multi-organ donation. Their organs may only be procured with proper consent, following the usual protocols and procedures.

Read more:

Would you donate your womb when you die?

In Australia, as elsewhere, organ donors are in short supply. But deceased donors might be found via existing donation registries and consent processes, such as those managed by DonateLife and NSW Organ and Tissue Donation Services.

Why investigate both types of donation?

It’s important to be able to compare the outcomes of living and deceased donation in similar recipients and contexts. This will inform future guidelines and policies around uterus donation, and determine whether it can become mainstream clinical practice.

Emerging evidence suggests deceased donation may yield better results for recipients. Using deceased donor organs allows longer veins and arteries to be retrieved, enabling better blood flow for the uterus and potentially greater success in transplants and pregnancies.

So although there are currently fewer cases of deceased donors, there are sound medical and ethical reasons for Australian uterus transplant research with both deceased and living donors.

![]()

Mianna Lotz provides independent ethical advice to the uterus transplant trial at Royal Hospital for Women.

– ref. What are uterus transplants? Who donates their uterus? And what are the risks? – https://theconversation.com/what-are-uterus-transplants-who-donates-their-uterus-and-what-are-the-risks-190443