COMMENT: By Matt McCarten

It’s time for progressive activists to step up. The working class needs you.

On May Day – International Workers Day – we have launched a new union: UTU for Workers Union. Our mission is to build a working class, grassroots, campaigning movement to stop exploitation and end workplace abuse in Aotearoa-New Zealand.

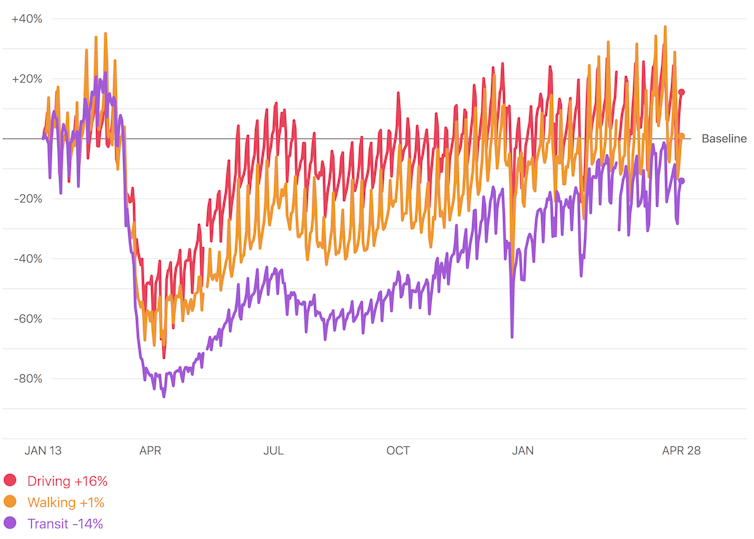

The international trade union movement is in a fight for relevancy to the majority of the working class. Decades of relentless attacks on the workers’ movement have been devastating.

In New Zealand, out of more than 1.5 million private sector workers, less than one in fourteen (7 pecent) are members of a union. If we exclude the large private companies, unionisation in the private sector is effectively non-existent.

More than half of the workers employed in the private sector do not even have the option to join a trade union nor be covered by a collective agreement.

Despite the good work the present unions do for their own members, the rest of the working class has lost ground in terms of income and protections.

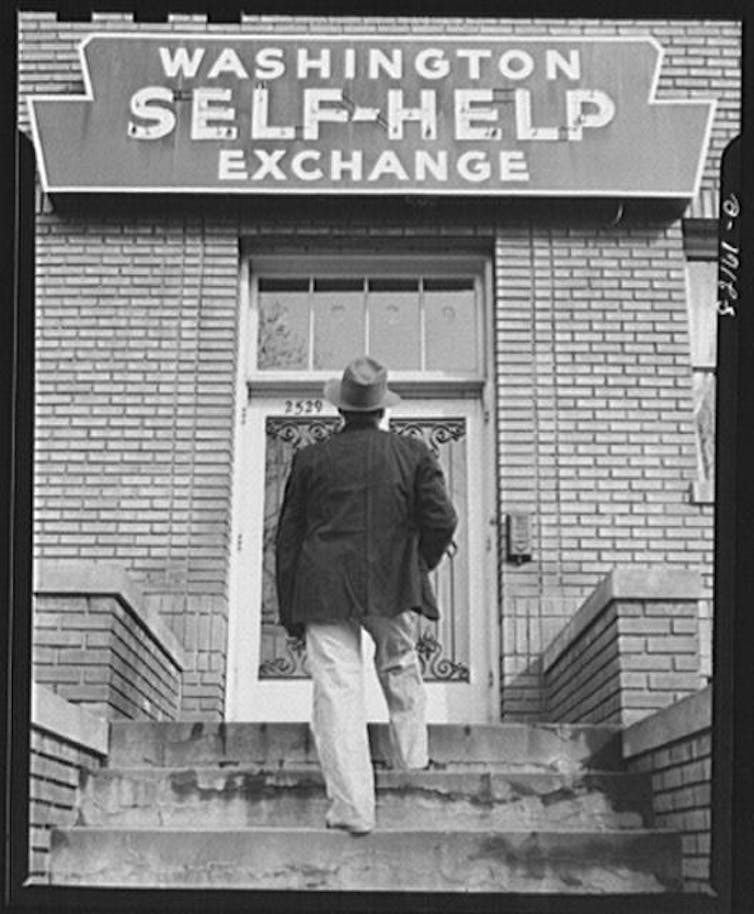

Non-unionised workers have no power to improve their position. They are at the mercy of their boss.

As a result, when workers in non-unionised workplaces have an employment dispute, they must seek support from an expensive lawyer, lay advocates, or a friend. Most exploited private sector workers receive no access to justice. Unscrupulous bosses know this.

The increase in vulnerable migrants and widespread casualisation, along with the growth of labour hire companies and dependent sole contractors, has seen the number of precariat workers in New Zealand explode.

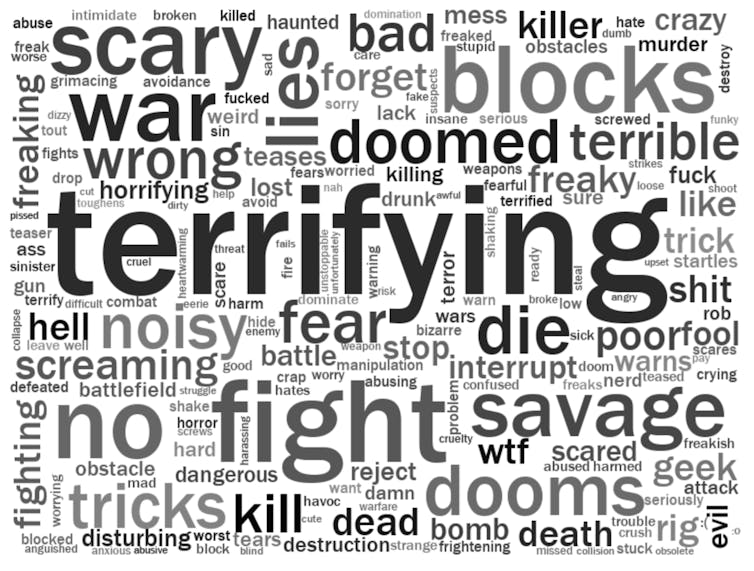

This has led to a culture of fear and isolation. As a result, workers’ power, incomes, job security and self-confidence have declined.

The situation is similar in most Western countries, and if we don’t shake it up, the international union movement in the private sector will descend into irrelevancy.

It is unacceptable that we morph into a network of staff associations for relatively better-off workers. That would be a betrayal of our history and all the working-class fighters who came before us.

A new activist movement

The old ways no longer work for the overwhelming number of private sector workers. The only question any serious worker rights activist must consider, is not if we protect and organise all workers, but only: how?

It is clear we need new forms of organisation.

I have been part of the One Union project group for the last three years. We have been actively trialing various models in our attempt to find a sustainable and effective way to meet the new challenge.

We believe we now have the solution. Today we announce the formation of the UTU for Workers Union.

The mission of UTU for Workers Union

Our purpose is to build a mass movement to stop exploitation – migrant and non-migrant – and end unchecked workplace abuse that non-unionised workers routinely suffer.

The use of UTU is deliberate. We summarise it in Māori terms – justice. When a victim is exploited or abused, their mana has been diminished and it must be restored. That is UTU.

As the first step, we have to actually help individual workers with their immediate problem. For the last year we have been providing representation to any worker from non-unionised workplaces who needs help.

The jungle of predator employment advocates and lawyers scamming vulnerable workers is sickening. They get screwed by the boss, and then again by their advocates, some of whom do sweetheart deals with bosses.

The advocate gets their fee, but the worker is forced to accept a few crumbs. Simply outrageous.

The good news is that when we have backed up our representation with a direct campaign, through picketing or media exposure, the exploitative boss has realised the power of the worker feeling they have got justice.

More careful in future

The boss knows to be more careful in the future. We have had some success in having bosses agree to ongoing compliance monitoring.

We have found that workers want to join a union. In almost all occasions, there is no union. If there is, they don’t use their resources to help non-members.

That might make sense if you look at unions as business units, but completely wrong if you see them as a justice movement for workers. There are only two categories of workers – those in unions, and those we must get into unions.

Up until now we have not asked workers to join us. From today we will accept workers as members and supporters.

Our membership is open to everyone, whether they are employees, or dependent contractors. We will help any worker who is in distress.

What must unite us is not what work we do, or who our boss is. Instead, we have to join together as a working class.

The old and true clarion call, “an injury to one, is an injury to all”, is as relevant today as it ever was. All unionists must fight for justice for all workers.

If any applicant is from a unionised site or sector covered by another union, then of course they must join that union. It must be noted that we are solely focused on the vast majority of non-unionised private sector workers who are exploited and abused in the non-unionised world.

By having an inclusive and broad strategy, we believe many workers and allies will step up to build a powerful workers movement dedicated to stopping exploitation and workplace abuse.

How do we rebuild working class confidence?

We can do this in three phases.

Help victims first

If we claim to be pro-worker, we have to earn the right. Our first priority is to resolve individual workers’ immediate problems. This is the most important thing to anyone. Support any victim, and they become a union ally – and in time, an activist.

We currently force exploiters to pay thousands of dollars of unpaid wages and backpay legal underpayments. We have prevented unfair sackings, stopped harassment and bullying, and won compensation and fair outcomes for hundreds of workers.

In the last year alone, we have won hundreds of thousands of dollars for victims. This is only the tip of the iceberg. We need more people to help. Until they do, exploitation will continue.

Our case work is now carried out by the One Union Trust, which operates in partnership with the union. The trust has a dedicated legal team of three lawyers led by a former senior trade union official.

Confront criminal bosses directly

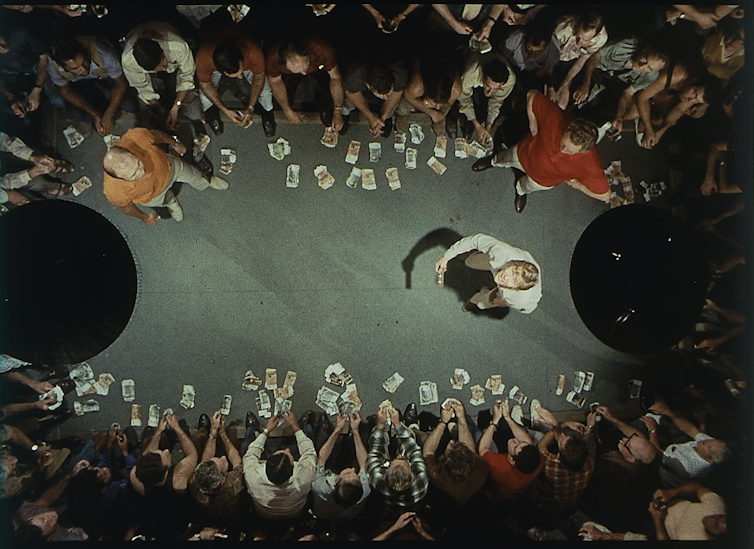

We have a dedicated UTU Squad. We hold UTU Vigils for Justice actions directly outside the businesses and homes of exploiters and abusers. Every community needs a local UTU Squad.

We name criminal bosses and expose injustices on our union website, utu.org.nz, and our Facebook page, @UTUForWorkersUnion.

We host a weekly radio programme on 104.6 Planet FM, Wednesdays at 12.40pm. We tell the truth about these exploiters and abusers.

We organise online Action Station petitions to mobilise support for victims, and let communities know about their local exploiters.

Build solidarity

After a boss has been found to breach minimum employment standards, we monitor compliance and enforce legal minimum codes. Thousands of workers in small workplaces don’t get their minimum entitlements. We can fix that through constant vigilance.

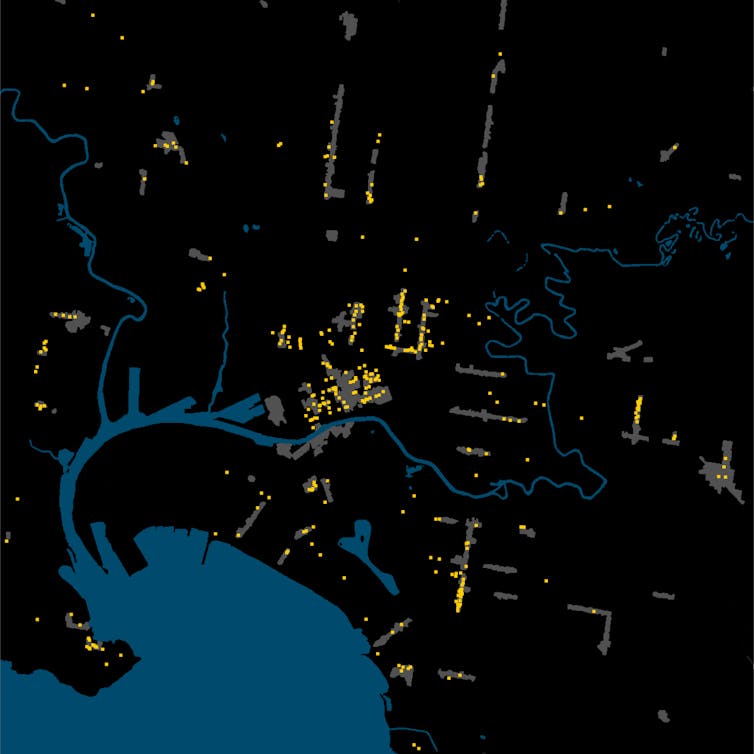

We also monitor visa compliance. 350,000 workers are reliant on a boss for their visas.

Workers will feel safer by regular check ins. Over time, we will patiently build a more collective confidence in their workplace.

Migrant exploitation

The most exploited and abused group of workers are migrant workers on temporary visas. Any project to eliminate worker exploitation in New Zealand must include campaigns that focus on migrant workers. We are judged as unionists on our commitment to the most vulnerable members of the working class.

The Migrant Workers Association partners with us and leads this work. The One Union Trust provides practical case representation for victims. MWA and UTU spearheads campaigns that rally the community against specific cases of injustice. Their fight is our fight.

A call to action

Progressive activists have to step up now. We need action. Go to this page for 8 practical steps you can do right now.

Matthew “Matt” McCarten is a New Zealand political organiser and trade unionist, of Ngāpuhi descent. He has been involved with several leftist or centre-left political parties, most prominently as the leader of the Alliance.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz