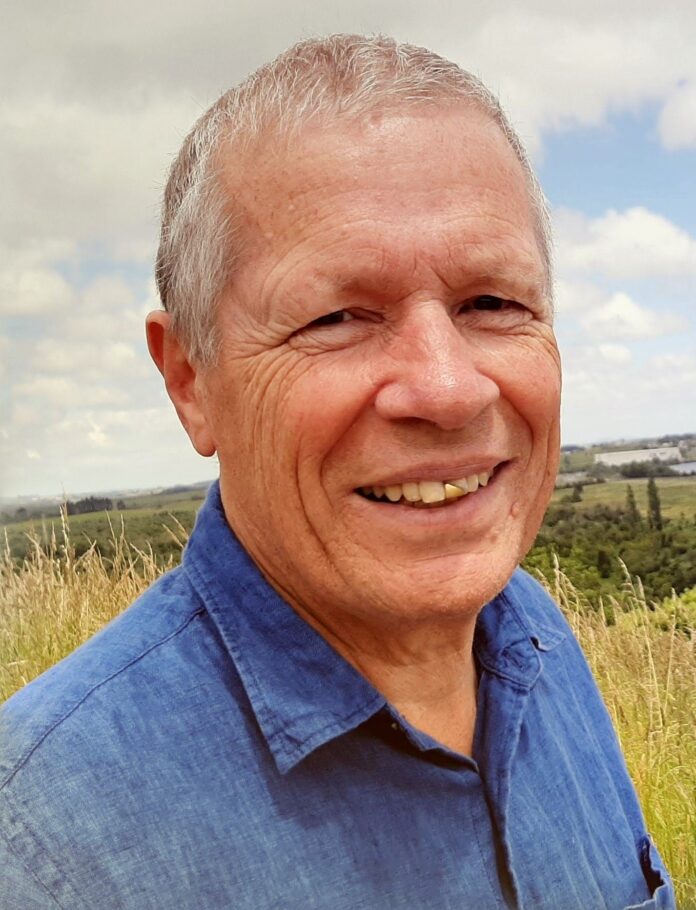

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jason Alexandra, Senior research fellow, Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

The national cabinet has announced plans to build an extra 1.2 million homes by July 1 2029. The construction, operation and maintenance of buildings accounts for almost a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions in Australia. If these new homes are built in a business-as-usual fashion, they will significantly increase national greenhouse gas emissions.

What if we committed to building homes that produced net negative emissions?

Put simply, such buildings remove more carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere than are emitted during their lifecycle. This includes emissions from producing building materials and construction through to the end of building life and demolition.

Building net-negative-emissions homes can be done. Examples have already been built overseas.

Building these homes in Australia would do much more than reduce national emissions. It would be a tangible symbol of our commitment to integrated problem-solving, in this case involving both housing and a climate-friendly future. We could produce houses that are part of the climate solution, not a big part of the problem.

Read more:

National Cabinet’s new housing plan could fix our rental crisis and save renters billions

So how do we build these homes?

Building homes that reduce rather than add to CO₂ emissions will require different planning, design, materials and construction methods.

For a start, the orientation of the buildings will have to be improved. In southern Australia, for example, ensuring living areas face north will reduce the need for heating by achieving greater sun exposure in winter. In summer, shade from the eaves of rooftops or awnings will help keep the home cool.

The design would use passive house principles. These require much better insulation to keep heat in during winter, and out during summer. Building airtight homes – known as a tight building envelope – avoids unwelcome heat gain or loss.

A house built like this massively reduces energy use in both winter and summer. Better thermal comfort is good for the occupants’ health too.

Read more:

Feeling frozen? 4 out of 5 homes in southern Australia are colder than is healthy

Better planning includes providing tree cover and green space to moderate increasingly extreme temperatures and flooding. Tree cover and green space also encourage active travel such as walking and cycling, which has many benefits.

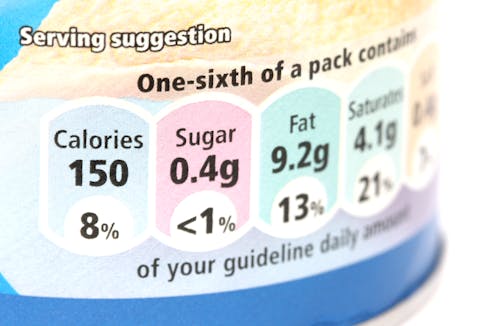

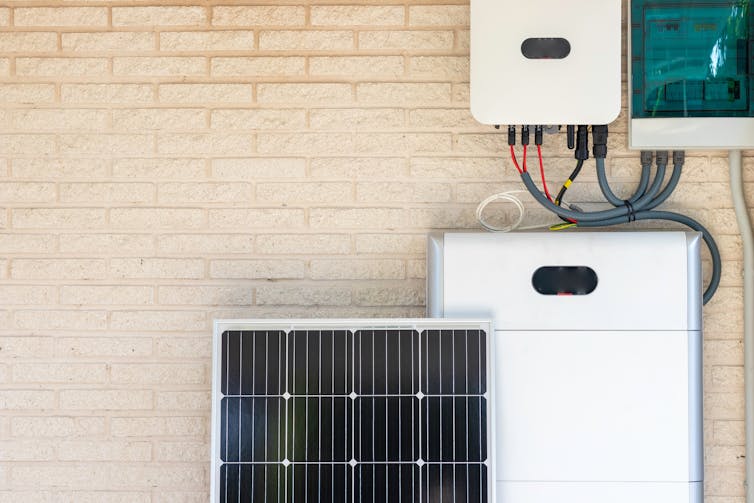

Using materials such as low-emission concrete and negative-emission plasterboard, which absorbs CO₂ from the air, can reduce the emissions associated with construction. Homes with solar panels or solar tiles, integrated with batteries and all-electric appliances, can produce more energy than they use during their operation. They’re budget-friendly too.

At the end of the building’s life, recycling the materials in a circular economy will reduce waste. Currently, building activity accounts for 40% of our landfill waste.

Read more:

Turning the housing crisis around: how a circular economy can give us affordable, sustainable homes

Have we the capacity to do most of this right now? Yes. Examples of buildings with low, zero or negative net emissions already exist in the United Kingdom and the European Union.

And more options are coming online every day. There are so many opportunities to demonstrate best practice and produce houses of the future efficiently.

Even now, sustainable buildings cost little more upfront. The premium for sustainability ranges from -0.4% to 21% compared to a conventional building. And they save from 24% to 28% on running costs over their lifetime.

HDValentin/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

And what is the role of government?

The benefits of aiming for net-negative-emissions housing are many. It would reskill the building sector, generate new industries, build confidence in public policy, boost national pride and show that governments can solve problems in ways that tackle social equity, health and environmental concerns.

However, realising such ambitions requires action on several fronts.

First, it requires political will to take ambitious action on climate change. Implementation calls for skilful execution and sharing of risks between government and industry. This can be done by, for example, subsidising training and certification in the use of new building materials and approaches and supporting the industry to make these changes.

Climate-friendly building technology is now demonstrated in buildings across Australia. Building 1.2 million homes that use such technology would scale it up, driving down costs. Building this many climate-friendly homes would be good for developing future-ready trade and professional skills and the capacity of the local building industry supply chain.

Second, the Commonwealth would need to adopt clear targets and criteria. The states, territories and building industry should then be left to work out how best to meet them in different local circumstances.

Third, any national housing programs should be a catalyst for good design and innovation in construction. This includes mandating emission and energy targets for the promised new housing stock. For example, New Zealand mandates that new buildings are constructed to provide thermal resistance.

New housing programs should also promote innovative designs. This could include sponsoring prizes for excellence in sustainable housing.

Read more:

How ‘net-zero’ and ‘passive’ houses can cut carbon emissions — and energy bills

Fourth, new housing programs should deliver system-wide solutions integrated with energy and water networks. Progress has begun on updating urban systems in line with climate-friendly design principles for water and energy.

For example, Hornsby Shire Council has been applying water-sensitive urban design principles since the 1990s through the use of rainwater tanks, biofilters and raingardens, stormwater harvesting and wastewater recycling and reuse. The ACT government has adopted these principles in its Territory Plan.

The knowledge exists to create suburbs that generate and store their own electricity. Community batteries are operating in North Fitzroy and in suburbs across Western Australia. The ACT has plans for a community battery serving the whole territory.

As anyone with a mortgage knows, houses are long-term commitments. Building all of the promised 1.2 million homes in a future-friendly way would show our governments recognise both the long-term imperative of climate action and this immediate opportunity.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Better than net zero? Making the promised 1.2 million homes climate-friendly would transform construction in Australia – https://theconversation.com/better-than-net-zero-making-the-promised-1-2-million-homes-climate-friendly-would-transform-construction-in-australia-211825