Source: Radio New Zealand

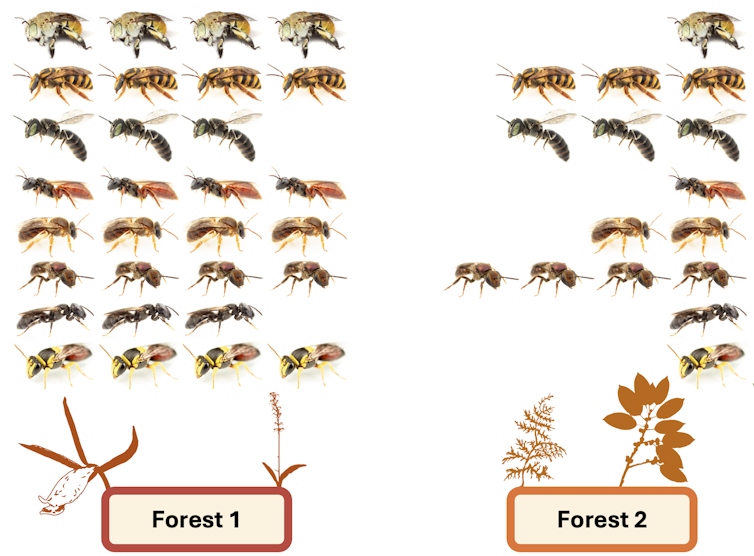

There are 42 people registered with individual real estate license who are aged over 83. RNZ

If you picture a real estate salesperson, you probably don’t imagine someone living in a retirement village. But it might be more common than you think.

Ray White general manager and licensee agent Antonia Baker can remember having a meeting with a client in a retirement village at one point, talking about selling her portfolio.

“As I walked out of the lift, I spotted a someone that I know as a real estate agent in West Auckland. And I could tell from the conversation that she was having with the people around her that she was a resident, not visiting like I was. So she was still getting up on a Saturday morning and trotting out to open homes as a Ryman’s resident.”

Real Estate Authority data shows that Baker’s acquaintance is probably not the only real estate salesperson in that situation.

There are 42 people registered with individual real estate license who are aged over 83. Another 168 are aged between 78 and 82. More than 3560 are aged between 73 and 77.

“I have a feeling that’s going to be me one day … why wouldn’t you?” Baker said.

“Some of them are actually quite high volume … There are a couple of legends in the industry who are still quite happily trading and trading decent volumes.”

It isn’t just the older crowd proving stickability, either. Despite a soft housing market, the number of people working in it has stayed relatively constant in recent years.

At the end of October 2025, there were 15,980 active real estate licenses, compared to 15,540 the year before and 15,870 in 2023.

There were 23,078 new licenses issued in the year to June last year, up 22 percent from the same time the year before. There was a 18.4 percent jump in the number of branch manager licenses active, a 1.1 percent increase in salespeople and a 0.9 percent drop in the number of individual agents.

Baker said people who had made it through the pandemic years had probably figured out a way to keep going.

“You were resilient by that time. My assumption around that was that we had baked in sufficient resilience into the industry and into people’s roles and their businesses by that time, that the external factors didn’t have all that much of an effect.

“And if I think about our network, it has just done so much to help the agents that work within it to drive their businesses and to make them resilient so that it doesn’t matter what the trading environment is, we can still survive.”

Real Estate Authority chief executive Belinda Moffat. Supplied

Real Estate Authority chief executive Belinda Moffat said the number of real estate licenses was down from a peak of nearly 1700 in the post-Covid boom.

“We had that really hot market, and … that’s when we saw a really sharp increase in joiners, so June 2022, we had nearly 17,000 active licenses, and we were issuing about 2600 new licenses a year.

“We then had a bit of a drop over a little bit of a period of time, and we’ve now got about 15,914, and we’ve issued in the last year just over 2000, so there has been, it does shift and fluctuate with the markets, but at the moment, it’s sort of holding steady.”

She said it was noticeable that a lot of people stuck with the industry for a long time.

“I think there’s a number of reasons why people come to real estate of itself.

“I think obviously the economic environment there is … I think people are exploring different professions, but I’d say that the reason people have come to real estate or also why they may not have left real estate is because it offers flexibility.

“Some people find it’s a great profession where you’re working with people, you’re helping people to realise their aspirations of a home and a business or a farm. It’s a pretty busy and dynamic profession, but it is also one that does offer a bit of independence. Most of our licensees are contractors, but having said that, they do have to meet both the expectations of our regulatory system and they also have to meet the expectations of the agency that they work for.”

How much is earned?

Collectively, there was about $70.3 billion in residential real estate sales through salespeople last year, according to Cotality, which at a rate of 3 percent commission could have netted real estate salespeople $2.1b or about $130,000 each. But that amount is generally split between the salesperson who makes the sale and the agency they work for. Some earn significantly more and others much less.

There were about 80,000 sales.

In 2023, the $56b in sales would have made agents about $1.68b or $105,860 each.

Moffat said people should not expect the job to be easy money. Some people left after a couple of years, she said.

“Being a real estate licensee is not an easy job. There is a lot that’s expected of our profession, they have to be over 18, got to have the qualifications, they have to be fit and proper, they have to undertake ongoing CPD or education every year, and then they have to meet the standards of our Code of Conduct that’s overseen by REA, and they can face complaints and disciplinary processes if they don’t, so they have to know a huge amount in order to be successful, and those first couple of years can be pretty tough.

“You’ve got to have some good financial backing, because you’ll look for your listings, then you might get your first couple of listings through people that you know in your networks, but then you’ve got to really be able to just make sure you maintain a pipeline, so it does require a lot of hard work, it’s like starting your own business, you’ve got to really be prepared for getting yourself through the slower months, as well as working hard when you do have a couple of listings on the go, so it’s a profession that does require some really concentrated work, and it’s not surprising because you’re always dealing with people who are perhaps engaging in the most significant transaction they will ever engage in, and it’s full of emotion and risk and financial obligations.”

Some people were working more than one job when the market was tougher, she said.

“That’s something we’ve seen in the cooler market, and as I said, the flexibility of the role can add to that, but at the same time, where they do have a listing, then they are having to work really hard to deliver the best service they can to their customers and clients and meet all the demands that go with being part of a profession that does have quite a few requirements for people to meet.”

Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub. Supplied

Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub said people would “live and die” by their sales.

“It’s a very high risk gamble in good markets it works but the way it works is the offices tend to have quite a lot of base income from the advertising and those bits and pieces. So they can sustain a group of people and then there is the whole bunch of people who are at risk.

“If you’re at the top and you’ve been around for a long time … you’ve had some spectacular years. I’m not surprised people are not leaving. My understanding is the more senior you are the less turnover there is. You’re less likely to be out there doing the putting up the signs and those kinds of things and in more of a leadership role. Those positions are still quite lucrative and they’ve been through many cycles so they know how to manage that.”

Lincoln University professor of property studies Graham Squires said people sometimes teamed up to share commission, which also helped.

“If you get say 4 percent on an $800,000 house you could be getting $32,000, so there’s probably enough in the market for people to say well as long as I break even or get a few sales, enough to keep me going, that will keep me in the industry.

“You could argue estate agents have a mindset where they’re optimistic that the market will improve. We see a lot of professional institutions talking up the market a lot even when it might not need to be talked up.”

Change coming?

Moffat said there was change happening. Salespeople were being given guidance in the use of AI.

Baker said salespeople were being offered training on how to “beat the bot”.

“I think fundamentally it is what everyone laughingly refers to as a belly-to-belly transaction. There’s no getting around the requirement for a human. And in fact, it’s the human that tips it over the line, not the bot. And it will always be like that, always.”

Lincoln University professor of property studies Graham Squires. Supplied

Squires said flat-fee competitors had not been able to get as much of a foothold in the industry as might have been expected, given consternation sometimes expressed about the level of real estate commission.

“I think the franchises probably have value to add and have some power and weight in the market in terms of reach and marketing and those sorts of things.

“I suppose they have education and marketing and training that’s allied with being part of the franchise that you contribute to when you make the sales.

“There’s a few big players … some of the larger organisations do buyouts and things like that so it sort of evolves in a larger space.”

Eaqub said it was a difficult industry to change. “It’s your biggest purchase or sale and tradition and brand awareness and trust and all those things matter a great deal. It’s not a price driven thing for a lot of people, if you’re spending millions of dollars or hundreds of thousands of dollars one percentage point here or there is like in the margin of error in terms of house prices going up and down.”

Baker said when the economy was difficult, people tended to move towards brands they knew.

“Then they tend to go back to the old, big, tried and tested providers. And I think that is the same in our industry. When the economy gets a bit scary, people go back to the big brands that they trust that have been around for 125 years and that they know.”

Sign up for Money with Susan Edmunds, a weekly newsletter covering all the things that affect how we make, spend and invest money.

– Published by EveningReport.nz and AsiaPacificReport.nz, see: MIL OSI in partnership with Radio New Zealand