Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Martin Jucker, Lecturer in Atmospheric Dynamics, UNSW Sydney

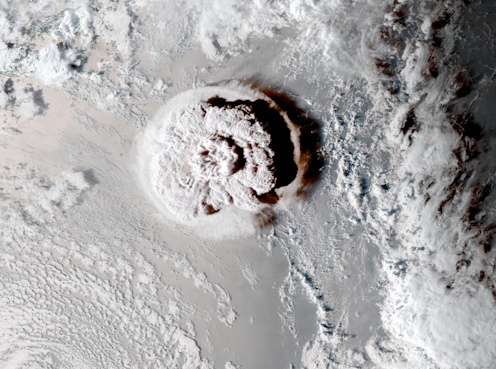

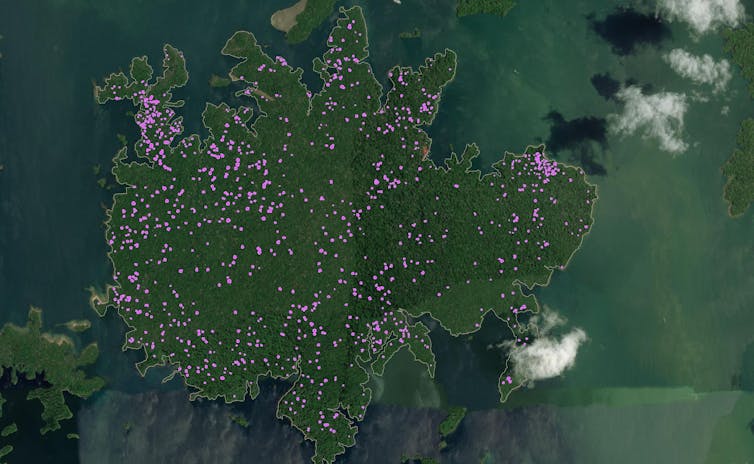

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai (Hunga Tonga for short) erupted on January 15 2022 in the Pacific Kingdom of Tonga. It created a tsunami which triggered warnings across the entire Pacific basin, and sent sound waves around the globe multiple times.

A new study published in the Journal of Climate explores the climate impacts of this eruption.

Our findings show the volcano can explain last year’s extraordinarily large ozone hole, as well as the much wetter than expected summer of 2024.

The eruption could have lingering effects on our winter weather for years to come.

A cooling smoke cloud

Usually, the smoke of a volcano – and in particular the sulphur dioxide contained inside the smoke cloud – ultimately leads to a cooling of Earth’s surface for a short period.

This is because the sulphur dioxide transforms into sulphate aerosols, which send sunlight back into space before it reaches the surface. This shading effect means the surface cools down for a while, until the sulphate falls back down to the surface or gets rained out.

This is not what happened for Hunga Tonga.

Because it was an underwater volcano, Hunga Tonga produced little smoke, but a lot of water vapour: 100–150 million tonnes, or the equivalent of 60,000 Olympic swimming pools. The enormous heat of the eruption transformed huge amounts of sea water into steam, which then shot high into the atmosphere with the force of the eruption.

Japan Meteorological Agency, CC BY

All that water ended up in the stratosphere: a layer of the atmosphere between about 15 and 40 kilometres above the surface, which produces neither clouds nor rain because it is too dry.

Water vapour in the stratosphere has two main effects. One, it helps in the chemical reactions which destroy the ozone layer, and two, it is a very potent greenhouse gas.

There is no precedent in our observations of volcanic eruptions to know what all that water would do to our climate, and for how long. This is because the only way to measure water vapour in the entire stratosphere is via satellites. These only exist since 1979, and there hasn’t been an eruption similar to Hunga Tonga in that time.

Follow the vapour

Experts in stratospheric science around the world started examining satellite observations from the first day of the eruption. Some studies focused on the more traditional effects of volcanic eruptions, such as the amount of sulphate aerosols and their evolution after the eruption, some concentrated on the possible effects of the water vapour, and some included both.

But nobody really knew how the water vapour in the stratosphere would behave. How long will it remain in the stratosphere? Where will it go? And, most importantly, what does this mean for the climate while the water vapour is still there?

Those were exactly the questions we set off to answer.

We wanted to find out about the future, and unfortunately it is impossible to measure that. This is why we turned to climate models, which are specifically made to look into the future.

We did two simulations with the same climate model. In one, we assumed no volcano erupted, while in the other one we manually added the 60,000 Olympic swimming pools worth of water vapour to the stratosphere. Then, we compared the two simulations, knowing that any differences must be due to the added water vapour.

NASA

What did we find out?

The large ozone hole from August to December 2023 was at least in part due to Hunga Tonga. Our simulations predicted that ozone hole almost two years in advance.

Notably, this was the only year we would expect any influence of the volcanic eruption on the ozone hole. By then, the water vapour had just enough time to reach the polar stratosphere over Antarctica, and during any later years there will not be enough water vapour left to enlarge the ozone hole.

As the ozone hole lasted until late December, with it came a positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode during the summer of 2024. For Australia this meant a higher chance of a wet summer, which was exactly opposite what most people expected with the declared El Niño. Again, our model predicted this two years ahead.

In terms of global mean temperatures, which are a measure of how much climate change we are experiencing, the impact of Hunga Tonga is very small, only about 0.015 degrees Celsius. (This was independently confirmed by another study.) This means that the incredibly high temperatures we have measured for about a year now cannot be attributed to the Hunga Tonga eruption.

Disruption for the rest of the decade

But there are some surprising, lasting impacts in some regions of the planet.

For the northern half of Australia, our model predicts colder and wetter than usual winters up to about 2029. For North America, it predicts warmer than usual winters, while for Scandinavia, it again predicts colder than usual winters.

The volcano seems to change the way some waves travel through the atmosphere. And atmospheric waves are responsible for highs and lows, which directly influence our weather.

It is important here to clarify that this is only one study, and one particular way of investigating what impact the Hunga Tonga eruption might have on our weather and climate. Like any other climate model, ours is not perfect.

We also didn’t include any other effects, such as the El Niño–La Niña cycle. But we hope that our study will stir scientific interest to try and understand what such a large amount of water vapour in the stratosphere might mean for our climate.

Whether it is to confirm or contradict our findings, that remains to be seen – we welcome either outcome.

![]()

Martin Jucker receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Tonga’s volcanic eruption could cause unusual weather for the rest of the decade, new study shows – https://theconversation.com/tongas-volcanic-eruption-could-cause-unusual-weather-for-the-rest-of-the-decade-new-study-shows-231074