Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Gabriel C Rau, Lecturer in Hydrogeology, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

Under your feet lies the world’s biggest reservoir. Groundwater makes up a whopping 97% of all usable freshwater. Where is it? In the voids between grains and cracks within rocks. We see it when it rises to the surface in springs, in caves, or when we pump it up for use.

While groundwater is often hidden, it underpins ecosystems around the world and is a vital resource for people.

You might think groundwater would be protected from climate change, given it’s underground. But this is no longer the case. As the atmosphere continues to heat up, more and more heat is penetrating underground. There is already considerable evidence that the subsurface is warming. The heat shows up in temperature measurements taken in boreholes around the world.

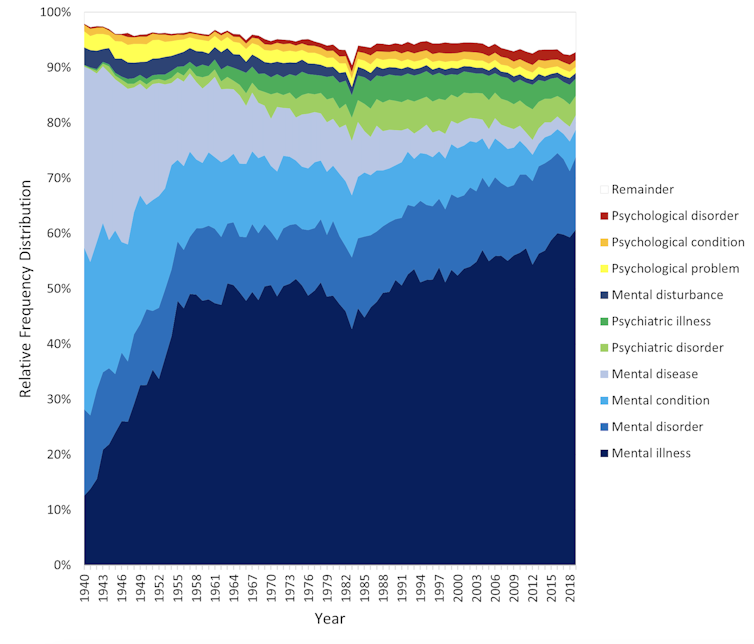

Our team of international scientists have combined our knowledge to model how groundwater will heat up in the future. Under a realistic middle of the road greenhouse gas emission scenario, with a projected mean global atmospheric temperature rise of 2.7°C, groundwater will warm by an average of 2.1°C by 2100, compared to 2000.

This warming varies by region and is delayed by decades compared to the surface, because it takes time to heat up the underground mass. Our results can be accessed by everyone globally.

Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock

Why does it matter?

You might wonder what the consequences of hotter groundwater will be.

First, the good news. Warming beneath the land’s surface is trapping 25 times less energy than the ocean, but it is still significant. This heat is stored in layers down to tens of metres deep, making it easier to access. We could use this extra heat to sustainably warm our homes by tapping into it just a few meters below the surface.

The heat can be extracted using heat pumps, powered by electricity from renewable energies. Geothermal heat pumps are surging in popularity for space heating across Europe.

Unfortunately, the bad news is likely to far outweigh the good. Warmer groundwater is harmful for the rich array of life found underground – and for the many plants and animals who depend on groundwater for their survival. Any changes in temperature can seriously disrupt the niche they have adapted to.

To date, the highest groundwater temperature increases are in parts of Russia, where surface temperatures have risen by more than 1.5°C since 2000. In Australia, significant variations in groundwater temperatures are expected within the shallowest layers.

Groundwater regularly flows out to feed lakes and rivers around the world, as well as the ocean, supporting a range of groundwater dependent ecosystems.

If warmer groundwater flows into your favourite river or lake, it will add to the extra heat from the sun. This could mean fish and other species will find it too warm to survive. Warm waters also hold less oxygen. Lack of oxygen in rivers and lakes have already become a major cause of mass fish deaths, as we’ve seen recently in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin.

Cold water species such as Atlantic salmon have adapted to a water temperature window provided by continuous cool groundwater discharge. As these thermal refuges heat up, it will upend their breeding cycle.

Marek Rybar/Shutterstock

Groundwater is vital

In many parts of the world, people rely on groundwater as their main source of drinking water. But groundwater warming can worsen the quality of the water we drink. Temperature influences everything from chemical reactions to microbial activity. Warmer water could, for instance, trigger more harmful reactions, where metals leach out into the water. This is especially concerning in areas where access to clean drinking water is already limited.

Industries such as farming, manufacturing and energy production often rely on groundwater for their operations. If the groundwater they depend on becomes too warm or more contaminated, it can disrupt their activities.

Our study is global, but we have to find out more about how groundwater is warming and what impact this could have locally. By studying how groundwater temperatures are changing over time and across different regions, we can better predict future trends and find strategies to adapt or reduce the effects.

Global groundwater warming is a hidden but very significant consequence of climate change. While the impacts will be delayed, they stretch far and wide. They will affect ecosystems, drinking water supplies and industries around the world.

![]()

Gabriel Rau receives funding from the German Research Council (DFG) for research on subsurface heat transport, though not related to this article.

Barret Kurylyk receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Canada Research Chairs Program for research related to this article.

Dylan Irvine receives funding from the Australian Research Council, The National Environmental Science Program and the Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia, although the research in the research discussed here is independent of these research programs.

Susanne Benz was supported through a Banting postdoctoral fellowship, administered by the Government of Canada and since October 2022 as a Freigeist Fellow of the Volkswagen foundation

– ref. Groundwater is heating up, threatening life below and above the surface – tag:theconversation.com,2011:article/229177