Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

“Productivity” might sound a nerdy word to many, but improving it is vital for a more affluent life for Australians in coming years. At the moment it is languishing.

Investigating ways in which our national productivity can be improved is at the heart of the work of the Productivity Commission, headed by Danielle Wood.

Wood is an economist and former CEO of the Grattan Institute. Picked by Treasurer Jim Chalmers for the PC job, she has already acquired a reputation for being willing to express forthright views, even when they don’t suit the government. She joins us today to talk about the tasks ahead, the commission’s work and some of the current big issues.

On Australia’s weak productivity numbers, Wood highlights what steps the government can and can’t take:

There’s a lot in productivity that’s outside of government’s control. So we sometimes talk about it like it’s something that government does to the economy. There’s a lot around technology, the pace of change and diffusion of change that are critically important for productivity that’s largely outside of government’s hands.

There’s no sort of single lever that you pull that makes all the difference. And, you know, if you looked at the Productivity Commission’s last big review of productivity released at the start of last year, you definitely get that sense.

If I was to pick just a small number […] of what I think are critically important areas. Sensible, durable, long-term market-based approach to climate policy that’s going to allow us to make the huge transition, including the energy transition that we need in the lowest possible cost way. That’s hugely important for long-run productivity. Housing: fixing the housing challenge and that’s got to go to some pretty serious work being done on planning policy, which I think is really important.

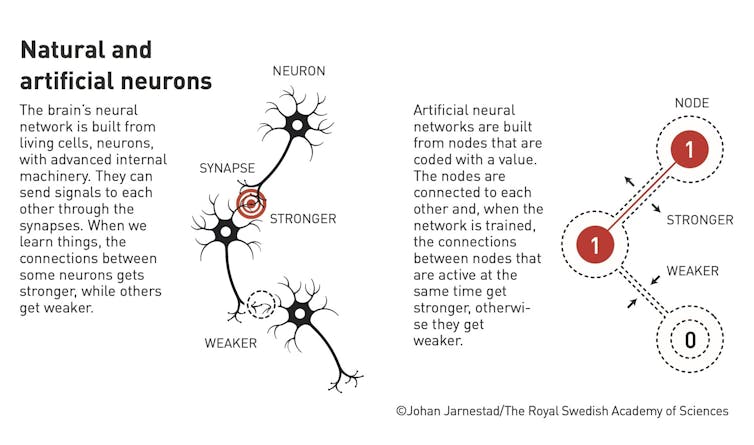

Then I would point to policies that support the rollout of new technologies. As I said before technological change is critical for productivity growth. So policies that build the right environment, particularly for big changes in technology like AI. So there you’re looking at the regulatory environment, your data policies, your IP policies. They all need to be working together.

If I can sneak in one more, I would put the government’s announcement that it will revitalise national competition policy, and I think that’s a really exciting one. And if it’s done well, if they can actually get the states to come to the table and agree on areas where we can reduce regulatory and other barriers to competition across the country, that’s a really important lever for getting economic dynamism moving again.

How has working from home has affected productivity?

Look, it’s a very big change, and you don’t often get these kinds of really sharp structural shifts in behaviour and in labour markets, and we’re still learning about it.

The research tends to suggest that hybrid work, so working at home sometimes and in the office sometimes, […] doesn’t seem to have negative productivity impacts If anything, slightly positive productivity benefits, and it has big benefits to individuals in terms of giving them flexibility, avoiding the commute and particularly for things like women’s workforce participation. I think it’s been really helpful and positively influential.

On the other hand, fully remote work, which is rarer – there is some evidence if you’re not ever coming into the office, you miss out on some of the spill-over benefits of sharing ideas, the kind of water-cooler effects, training and development.

I work from home one day a week, on Monday, and I do no meetings or calls on that day. And I do all my deep, deep work on Monday, and then the rest of the week I’m in the office and back to back.

With housing policy front and centre and a debate about whether changes to negative gearing and the capital gains discount should be made, Wood hoses down how much difference that would make:

It’s not a silver bullet on the house price front. There may be other reasons that you make those changes, particularly if you were doing a kind of broader base tax reform exercise. I would say that you’d want to have those on the table. But when it comes to housing challenges, there’s probably some bigger ones there. The ones […] around planning, around construction productivity, around workforce, are going to be more important in the long term to getting the housing challenge right.

Wood was initially had concerns about the Future Made in Australia policy. Now she says she now is pleased with where the government has landed:

Look, I’m certainly very pleased with the guardrails that the government have put in place. I think the publishing of the national interest framework, which puts a lot more economic rigour around the assessments of particular sectors looking for support, was a really important development.

Certainly puts my mind at ease that there is a lot of rigour around who gets support. Because as you said there is always a risk with these types of policies that we end up wasting money for supporting industries that don’t have a good case for economic support from the taxpayer.

— Transcript —

Michelle Grattan: Danielle Wood is almost a year into her post as head of the Productivity Commission. A leading economist and formerly chief of the think tank the Grattan Institute, Wood has taken the Commission’s message out into the public arena. She’s been refreshingly forthright in her willingness to critique government policies, most notably the Future Made in Australia industry policy, for which legislation is due to pass Parliament soon. Languishing productivity is one of Australia’s major economic challenges. In this podcast, Danielle Wood joins us to discuss this and other issues.

Danielle Wood in your relatively brief time as head of the Productivity Commission, you’ve been out and about and publicly vocal a good deal more, I think, than your predecessors, sometimes criticising government policies. Did you decide on this strategy when you accepted the job? And how important do you think it is for the head of key institutions like the Commission and indeed the Reserve Bank to be willing to use their voices even when that might make the Government squirm a bit?

Danielle Wood: A very interesting question, Michelle. Look, I mean, I have been out and about a lot, and I certainly did make that a deliberate strategy. And that’s largely because I think organisations like the Productivity Commission have a really important role in informing and shaping debate and making the case for difficult policy reform. I think it’s true to say that any time I say something that might be seen as politically inconvenient for the government the media get excited. And there’s probably a lot more reporting on those comments than perhaps a lot of the other commentary I’ve been making. Making those sort of criticisms is definitely not something I do lightly. But I think there are circumstances where the PC has deep expertise and research in areas. And I think if the policy’s not as well designed as it could be that there can be a case for independent agencies like the PC to speak up. And in doing so I really hope that makes the debate stronger. I think it makes the policy responses stronger. And I think we’re fortunate to have a system with the degree of political maturity that allows that to happen. You know, there are actually not that many countries with an independent, broad ranging policy institution like the Productivity Commission. The fact that governments of various stripes have supported that role over several decades now – I think it makes it a really important and unique part of the policy landscape.

Michelle Grattan: Now productivity in Australia is languishing. What are the reasons, do you think, for this? And what are the top performing countries when it comes to productivity and how are they performing better?

Danielle Wood: This is a complicated one and I think it’s really important to differentiate, as I’ll do, Michelle, between what’s happened since COVID and the more business as usual world pre-COVID, because we’ve been on this crazy rollercoaster ride when it comes to productivity in the post-COVID period. It shot up very rapidly early on in COVID as we shut down parts of the economy because they were the lower productivity services sectors that mechanically made it go up. We then came down that hump as things reopened.

On the other side of COVID we’ve also had a very strong labour market just because of the very fast increase in working hours we’ve seen as unemployment’s come down, as borders have reopened, as people are working more hours. Our capital stock hasn’t kept up and that’s kept productivity really subdued in the post-COVID period. So we’re running at only about half a percent in the year to June.

In that period, most countries have been going through similar challenges. The US actually stands out as a very strong performer in this post-COVID period and we’re doing some work with the RBA at the moment looking at that and trying to understand that – it may be because of their COVID policies or because they’ve got a fairly substantial investment boom underway. It can be about differences in the labour market. But we’re looking at that question.

The more substantive piece, given that a lot of that is about the macro environment, is really the question of what are we recovering to? You’ll recall that that decade sandwiched between COVID and the GFC leading up to 2020 saw really weak productivity growth. We were running about 1.1% a year on average – the lowest level in 60 years. That was not just an Australian phenomenon. At that point, if you looked around the industrialised world, we saw that same sluggish productivity growth basically everywhere.

There’s a number of structural factors at play that we think contributed to that. One is the expansion of services sectors– they tend to be lower productivity. We’ve seen fewer gains from technological advancements – at least up to that point technology hadn’t played the same role in driving productivity improvements as it had in the past. A reduction in economic dynamism, so fewer new businesses being started, fewer people changing jobs. And just more generally lower levels of investment – it looked like businesses were scarred in a post-GFC world and were not investing in the way they had in the past. So there’s a lot of common factors across countries. The real question going forward is can we break free of some of those constraints and see productivity moving again?

Michelle Grattan: So what would you say would be the three most productivity enhancing measures that Australia could take in the short term?

Danielle Wood: You’re really going to try and pin my colours to the mast Michelle! So two things I think are really important to say at the outset of this conversation. First, there’s a lot in productivity that’s outside of government’s control. So we sometimes talk about it like it’s something that government does to the economy. There’s a lot around technology, the pace of change and diffusion of change that are critically important for productivity, largely outside of government’s hands.

The other thing to say is it’s a game of inches. You actually need governments to move across a range of different policy fronts at once. There’s no single lever that you pull that makes all the difference. And if you look at the Productivity Commission’s last big review of productivity released at the start of last year, you definitely get that sense. There were 70 recommendations, five big areas for reform.

But if I was to pick just a small number of critically important areas, and we will take some political constraints off the table here maybe for the purposes of this conversation… a sensible, durable, long-term market-based approach to climate policy that’s going to allow us to make the huge transition, including the energy transition that we need in the lowest possible cost way. That’s hugely important for long-run productivity.

Housing. Fixing the housing challenge. And that’s got to go to some pretty serious work being done on planning policy, which I think is really important. But there are a lot of other barriers to housing supply around the regulatory environment and workforce. And that matters because if you can’t build houses where people live close to jobs, if people can’t get into housing, they have reduced capacity to start their own businesses and take risks in the economy. That is a big drag on productivity over time.

Then I would point to policies that support the rollout of new technologies. As I said before, technological change is critical for productivity growth. So policies that build the right environment, particularly for big changes in technology like AI. There you’re looking at the regulatory environment, your data policies, your IP policies. They all need to be working together, of course we need to manage the risks associated with these new technologies, but we don’t want to be putting unnecessary impediments that would slow down technological change across the economy.

So those are three big areas. Actually, if I can sneak in one more… the Government has announced that it will revitalise national competition policy, and I think that’s a really exciting one. And if it’s done well, if they can actually get the states to come to the table and agree on areas where we can reduce regulatory and other barriers to competition across the country, that’s a really important lever for getting economic dynamism moving again.

Michelle Grattan: Just on housing, there’s been a lot of controversy lately, of course, around negative gearing and the discount. Do you think that it would be useful to change negative gearing arrangements and the capital gains discount? The Grattan Institute, where you came from, was a supporter of change. Do you agree with that?

Danielle Wood: You know, it’s not something that the Productivity Commission has done work on so I can’t talk about it from a PC perspective.

Michelle Grattan: But you are, beyond tax, you’re a tax expert.

Danielle Wood: Yes, indeed. But look, what we said in that Grattan work, which I think is important, is it’s not a silver bullet on the house price front. There might be other reasons that you make those changes, particularly if you were doing a kind of broader base tax reform exercise I would see that you’d want to have those on the table. But when it comes to housing challenges, there’s probably some bigger ones there. You know, the ones I was talking about before around planning, around construction productivity, around workforce, that are going to be more important in the long term to getting the housing challenge right.

Michelle Grattan: So you would say it is a second-order issue in terms of housing policy?

Danielle Wood: In terms of housing affordability that’s right. But there may be other reasons that you would look at it if you were looking at the tax system more broadly.

Michelle Grattan: Now, you mentioned services before, and they’re obviously an increasingly large part of our economy, and yet it’s hard to define productivity in this sector. For example, if you have a carer spending a longer time with a person in a nursing home, is that actually increasing productivity? Probably not, but it has other obvious benefits. So how do you deal with this non-market part of the economy?

Danielle Wood: It’s an incredibly important question and it’s a very difficult one, and I think there are two parts to it. So the thing you’re picking up with your aged care example is essentially the challenge of trying to measure service quality. Across the national accounts when we work out productivity we try and adjust for quality, and I think the ABS does that really well in some areas like housing and technology, there are ways that they control for quality change over time, but that is very hard to do in services.

The PC did some recent work where we looked at this question for health and we tried to control for improvements in health outcomes across a range of chronic diseases. And what we found is productivity is much higher than what would be measured using traditional techniques because we’ve seen these really big improvements in outcomes for treating chronic diseases that don’t get captured in the statistics. And that gets even harder, as you say, in areas like aged care. How do you measure the warmth of care or the quality of care? I think we just have to recognise that there will always be gaps in the statistics and they are not perfect when it comes to measuring quality of services.

The other big challenge when it comes to services is that historically we haven’t seen the same productivity gains in services as we’ve seen in areas like manufacturing or agriculture. Going forward, I think we can look at new technologies like AI and see potential for gains in some areas of government-provided services like health and perhaps education. But there are going to be other sectors, particularly those care sectors, where it is irreducibly human. You know, I say labour is the product, that spending time with people is what you are providing. And that means it’s just going to be harder to get productivity gains in those sectors. So none of that is to say that we shouldn’t provide these services and continue to support them and expand them where there is a good economic or social policy case to do so. But we need to recognise that the productivity gains will not be there in those areas as they are in other parts of the economy.

Michelle Grattan: Now you have a long-term interest in childcare and the Commission has just recommended a major expansion in government spending on early childhood education and care, but it does not envisage that this will in fact lift women’s participation in the workforce to any great degree. So is expanding childcare now mainly about educational equity rather than participation and productivity?

Danielle Wood: Well, I think the first thing to say is that childcare has been transformative for women’s workforce participation. And even in the last few years, Michelle, as you would know, as it’s become more affordable, we have seen big gains in workforce participation. Women’s workforce participation is now at record levels.

But it is true that you expect some of those gains to start to slow down as participation rises. And what we found in our report is not that there aren’t barriers to access and affordability that constrain women’s choices, but that childcare is a smaller part of that now. And things like the tax and transfer system, withdrawal of family tax benefits play a bigger role in the sort of workforce disincentives that we’ve been worried about for a long time. Critically, though, as you say, it’s the education benefits that really loom large here. And we found that kids that are going to get the most out of childcare in terms of their development and education are the ones that are accessing it least. So children from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to use care a lot less than other children. Helping those children get the benefits of care for development, for being school ready, is a critical social and economic opportunity.

Michelle Grattan: The pandemic saw a big shift to many people working from home, and this has continued to a considerable degree. Workers want it and indeed, in some companies, are demanding it. What are the productivity implications of this shift?

Danielle Wood: Yeah, look, it’s a very big change and you don’t often get these really sharp structural shifts in behaviour and in labour markets. And we’re still learning about it, you need to be modest about these things, but from the research and data we’ve seen to date, I’m much less concerned that it’s going to have a big negative impact as we might have been earlier on. And by that, I mean the research tends to suggest that hybrid work, so working at home sometimes and in the office sometimes, particularly well-managed hybrid work, doesn’t seem to have negative productivity impacts. If anything, it has slightly positive productivity benefits. And it has big benefits to individuals in terms of giving them flexibility, avoiding the commute. And particularly for things like women’s workforce participation I think it’s been really helpful and positively influential.

On the other hand, fully remote work, which is rarer… there is some evidence, again, the data is mixed, but some studies suggest that it may negatively affect productivity. If you’re not ever coming into the office, you miss out on some of the spill-over benefits of sharing ideas, the kind of watercooler effects, training, development. So, if we were in a world where everyone was working fully remotely I think I would be more concerned. But I think broadly, when it comes to hybrid work, the best evidence we have suggests it’s unlikely to be a drag on productivity.

Michelle Grattan: What about your own work? Do you work from home at all?

Danielle Wood: I work from home one day a week on Monday, and I do no meetings or calls on that day. And I do all my deep work on Monday. Then the rest of the week I’m in the office and back-to-back.

Michelle Grattan: Now, the government has made a number of important changes in the industrial relations area. It’s been a priority for it. How important are workplace arrangements to productivity and have the recent changes been positive or negative or mixed for our productivity challenge?

Danielle Wood: Look, it’s definitely fair to say that workplace relations policies matter for productivity. This is not an area that the Commission has been asked to look into for some time. I think the last time we did a serious review into workplace relations was a decade or so ago, Michelle. And in that review, we really talked about the balancing act that exists – the need to balance the need for good standards in the workplace and protections for workers, against the benefits that come with flexibility and the advantages of that for business. And at that time, we had suggestions for improvements, but we found that the system was working relatively well. There have been a number of changes since then, including in recent years. But without reviewing those in any detail, it’s difficult for me to comment on the broader impact of those particular changes.

Michelle Grattan: Treasurer Jim Chalmers indicated some time ago when he was talking about the reform of the PC that he wanted it to be active in the sphere of the energy transition. How have you responded to this?

Danielle Wood: Something that I’ve done since taking on the role of Chair is to recognise the need to build expertise in some key policy areas that aren’t going away. So we’ve developed a number of research streams, energy and climate being one of those. We are really building up a team that will continue to work on those issues and put out research on those issues over time. We have a new Commissioner, Barry Sterland, who has deep expertise in climate policy, so that’s an important part of building that internal expertise. So you will see us putting out a whole series of pieces on energy and climate and I think we’re really well-placed to make a constructive contribution in that sphere. So watch this space.

Michelle Grattan: Could you give us any detail of time or topic?

Danielle Wood: I am not able to do that at the moment for various complicated reasons, but there will certainly be material coming out next year.

Michelle Grattan: One thing that you made a media splash on was the Government’s Future Made in Australia program, its industry program aimed at supporting Australian industry in the transition to the green economy. You expressed some concern about it at the time. Are you now convinced that there are enough guardrails around this policy that it doesn’t become a waste of taxpayer money and that money won’t be going to rent seekers who don’t deserve or need it?

Danielle Wood: Look, I’m certainly very pleased with the guardrails that the Government has put in place. I think the publishing of the National Interest Framework, which puts a lot more economic rigour around the assessments of particular sectors looking for support, was a really important development. We think that it’s really important that those sector assessments be done before the government offers support to new areas. And we’ve encouraged things like the sort of public release of those assessments, which I believe will occur. So, I think provided that process gets used, it certainly puts my mind at ease that there is a lot of rigour around who gets support. Because as you said, you know, there is always a risk with these types of policies that we end up wasting money supporting industries that don’t have a good case for economic support from the taxpayer.

Michelle Grattan: So would the Commission be doing its own assessment of how this program is working after some time?

Danielle Wood: We are putting in a submission to the Treasury consultation process on the frameworks that might underpin the national interest assessments and the legislation, if it passes, I think requires ongoing consultation with the Commissioners as Treasury does these assessments. So we will continue to play an active role in this process going forward.

Michelle Grattan: Now, just finally, in a speech recently, you defended the role of economists in assessing government policies and programs. You were saying that they were able to tell, in your words, inconvenient truths, but you also had a go at your profession saying that many have been willfully blind to questions of distribution, arguing that it’s not their job to consider economic inequality. Can you just say what you’re getting at here and perhaps give some examples of this failing? And why do you think this blind spot is there?

Danielle Wood: Well let me let me give the plug for economists, Michelle, before we talk about all our failures. As I was trying to say in that speech, economists bring something really important to the table in policy discussions, and that is, you know, rigorous frame frameworks for thinking about trade-offs. And that’s really important in the policy world because you’ve got a million good ideas out there, as you know, but you’ve got scarce resources. Scarce time, scarce money. You need to prioritise and you need to make trade-offs. So economists can and should play a really important role in policy for that reason.

The blind spots I was talking about, as I said, there had been a sort of strain in the economics profession, I think, for a long time that basically said we’re focussed on questions of efficiency, we don’t do distribution. And I think that came from the fact that that was seen to involve value judgements that we don’t want to contend with. We’ve since learned a lot more about the way in which inequality can feed into growth, around the importance of issues like economic mobility. I think most economists would now understand that these are actually really important economic as well as social questions. In terms of where that played out – probably the place where it was most evident, and I think this is probably more squarely in the US and Australia, was around fallout to trade policy and trade liberalization. It was all about increasing the size of the pie, which it did very effectively. But it certainly never said that, you know, there wouldn’t be any losers from that. I think the learning was that you really have to care about the transition, that you have to work with the communities and workers that are affected if you’re doing a policy that’s broadly in the public good, but sees some people go backwards. I think we did that better in Australia than the US, but there are probably still some lessons to learn there.

The other area I was pointing out where I think economists haven’t always covered themselves with glory, more in the Australian context, was around opening up human services markets to competition. I think there were a number of areas where we were too enamoured with the idea that competition and consumer choice would drive good outcomes, and we just didn’t give enough thought to questions of provider incentives, the regulatory frameworks we would need in place. I think employment services and vocational education and training are key examples of that, and probably some of the challenges we face with the NDIS at the moment as well. So I think they were areas where some economists were a bit naive and certainly I think the thinking and the profession has progressed a lot about how we could do better in those types of markets.

Michelle Grattan: Danielle Wood, thank you so much for joining us today. We hope to hear continued bold words from you in the months and years ahead. That’s all for today’s Conversation Politics podcast. Thank you to my producer, Ben Roper. We’ll be back with another interview soon, but goodbye for now.

Michelle Grattan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Politics with Michelle Grattan: Danielle Wood on the keys to growing Australia’s weak productivity – https://theconversation.com/politics-with-michelle-grattan-danielle-wood-on-the-keys-to-growing-australias-weak-productivity-240793

![]()