Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mehmet Ozalp, Associate Professor in Islamic Studies, Director of The Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation and Executive Member of Public and Contextual Theology, Charles Sturt University

Who could have predicted that after nearly 14 years of civil war and five years of stalemate, the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria would collapse in just a week? With Assad’s departure, the pressing question now is what lies ahead for Syria’s immediate future.

When opposition fighters led by the group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) seized the major city of Aleppo in late November with minimal resistance, commentators widely believed it marked the beginning of the Assad regime’s downfall. Many anticipated a bitter fight to the end.

Assad was caught off guard, and his forces were clearly unprepared. He withdrew his remaining troops from Aleppo to regroup and gain time for reinforcements to arrive from Russia and Iran, and hope the opposition fighters would stop there.

It wasn’t to be. Emboldened by their swift success in Aleppo, HTS fighters wasted no time and advanced on Hama, capturing it with ease. They quickly followed up by seizing Homs, the next major city to the south.

Russia provided limited air support to Assad. But Iran, having depleted its forces in Hezbollah’s defence against Israel in Lebanon, was unable to offer significant assistance and withdrew its remaining personnel from Syria. Meanwhile, Assad’s frantic calls for support from Iraq did not go anywhere.

Seeing the writing on the wall, the morale of Assad’s forces and leadership plummeted. Fearing retribution in the event of the regime’s collapse, defections began en masse, further accelerating Assad’s downfall.

And on the last day, Assad fled the country, and his prime minister officially handed over power to HTS and its leadership. It marked the end of 54 years of Assad family rule in Syria.

The Assad legacy

The Assad family, including Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez al-Assad, will likely be remembered by the majority of Syrians as brutal dictators.

The modern state of Syria was established in 1920 following the Sykes-Picot Agreement in the aftermath of the first world war. Syria became a League of Nations mandate under French control, only gaining independence in 1944. Following a tumultuous period, including a failed unification with Egypt, the Ba’ath Party seized control in 1963 through a coup that involved Hafez al-Assad.

In 1966, Hafez al-Assad led another coup alongside other officers from the Alawite minority. This ultimately resulted in a civilian regime, with Hafez al-Assad becoming president in 1970.

Hafez al-Assad established himself as an authoritarian dictator, concentrating power, the military and the economy in the hands of his relatives and the Alawite community. Meanwhile, the Sunni majority was largely marginalised and excluded from positions of power and influence.

Hafez al-Assad is most infamously remembered for his brutal suppression of the opposition in 1982. The uprising, led by the Islamic Front, saw the opposition capture the city of Hama. In response, the Syrian army razed the city, leaving an estimated 10,000 to 40,000 civilians dead or disappeared and decisively crushing the rebellion.

Hafez al-Assad died in 2000, and, the least likely candidate, his younger son, Bashar al-Assad, assumed the presidency. Having been educated in the West to become a doctor, Bashar al-Assad projected a moderate and modern image, raising hopes he might usher in a new era of progress and democracy in Syria.

However, Bashar al-Assad soon found himself navigating a turbulent regional landscape following the September 11 2001 terror attacks and the US invasion of Iraq. In 2004, after the United States imposed sanctions on Syria, Assad sought closer ties with Turkey. He and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became friends, removing visa requirements between their countries and making plans to establish economic zones to boost trade.

Erdoğan and Assad then had a falling out during a series of events in 2011, a year that marked a turning point for Syria. The Arab Spring revolts swept into the country, presenting Assad with a critical choice: to pursue a democratic path or crush the opposition as his father had done in 1982.

He chose the latter, missing a historic opportunity to peacefully transform Syria.

The consequences were catastrophic. A devastating civil war broke out, resulting in more than 300,000 deaths (some estimates are higher), 5.4 million refugees, and 6.9 million people internally displaced. This will be Assad’s legacy.

Syria’s immediate challenges

Syria now has a new force in power: HTS and its leadership, spearheaded by the militant leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani. They will face immediate challenges and four key priorities:

1) Consolidating power. The new leadership will now try to ensure there are no armed groups capable of contesting their rule, particularly remnants of the old Assad regime and smaller factions that were not part of the opposition forces.

Critically, they will also need to discuss how power will be shared among the coalition of opposition groups. Al-Jolani is likely to become the founding president of the new Syria, but how the rest of the power will be distributed remains uncertain.

It seems the opposition was not prepared to take over the country so quickly, and they may not have a power-sharing agreement. This will need to be negotiated and worked out quickly.

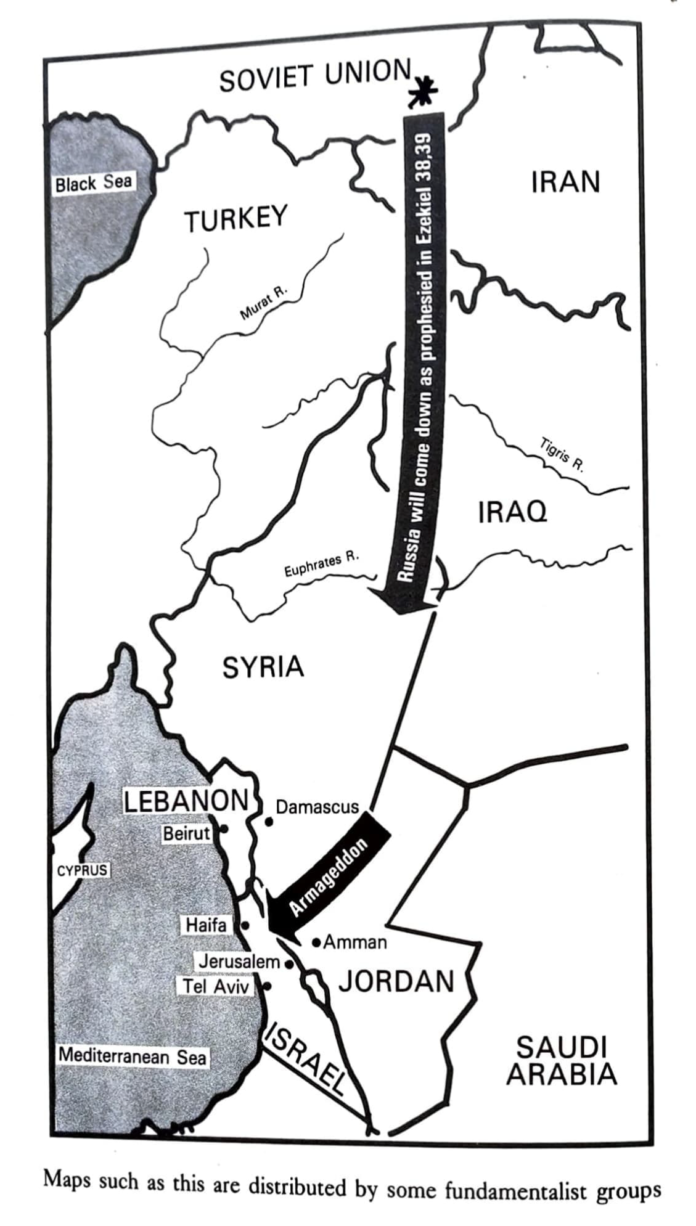

The new government will likely recognise the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the territories it controls as an autonomous region within Syria. An independent Kurdish state, however, will be strongly opposed by Turkey, the main external backer of the opposition.

Yet, history seems to be moving in favour of the Kurds. There is now the eventual possibility of an independent Kurdish state, potentially combining northern Iraq and northeastern Syria into a single entity.

2) International recognition. Syria is a very complex and diverse place. As such, the new government can only be sustained if it gains international recognition.

The key players in this process are Turkey, the European Union, the United States and Israel (through the US). It is likely all of these entities will recognise the new government on the condition it forms a moderate administration, refrains from fighting the Kurdish YPG, and does not support Hezbollah or Hamas.

Given their unexpected success in toppling Assad so quickly, the opposition is likely to accept these conditions in exchange for aid and recognition.

3) Forming a new government. The question on everyone’s mind is what kind of political order the opposition forces will now establish. HTS and many of the groups in its coalition are Sunni Muslims, with HTS having origins linked to al-Qaeda. However, HTS broke away from the terror organisation in 2016 and shifted its focus exclusively to Syria as an opposition movement.

Nevertheless, we should not expect a democratic secular rule. The new government is also unlikely to resemble the ultra-conservative theocratic rule of the Taliban.

In his recent interview with CNN, al-Jolani made two key points. He indicated he and other leaders in the group have evolved in their outlook and Islamic understanding with age, suggesting the extreme views from their youth have moderated over time. He also emphasised the opposition would be tolerant of the freedoms and rights of religious and ethnic minority groups.

The specifics of how this will manifest remain unclear. The expectation is HTS will form a conservative government in which Islam plays a dominant role in shaping social policies and lawmaking.

On the economic and foreign policy fronts, the country’s new leaders are likely to be pragmatic, open to alliances with the regional and global powers that have supported them.

4) Rebuilding the country and maintaining unity. This is needed to prevent another civil war from erupting — this time among the winners.

A recent statement from HTS’s Political Affairs Department said the new Syria will focus on construction, progress and reconciliation. The new government aims to create positive conditions for displaced Syrians to return to their country, establish constructive relations with neighbouring countries and prioritise rebuilding the economy.

Syria and the broader Middle East have entered a new phase in their modern history. Time will tell how things will unfold, but one thing is certain: it will never be the same.

Mehmet Ozalp is affiliated with Islamic Sciences and Research Academy.

– ref. After 54 years of brutal rule under the Assads, Syria is at a crossroads. Here are 4 priorities to avoid yet another war – https://theconversation.com/after-54-years-of-brutal-rule-under-the-assads-syria-is-at-a-crossroads-here-are-4-priorities-to-avoid-yet-another-war-245538