Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Richard Vaughan, PhD Researcher Sport Integrity, University of Canberra

Warren Buffet once famously said: “you only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out.”

In this context, the US government’s decision this month to withhold its annual funding to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), has exposed WADA’s reliance on the nations with the highest numbers of elite athletes as it aims to lead “a collaborative worldwide movement for doping-free sport”.

The US has taken issue with WADA’s decision not to appeal the China Anti-Doping Agency’s finding of “no-fault” following the contamination of 23 Chinese swimmers in 2021.

The international community promotes “clean” sport for fairness between competitors and to protect the integrity of the competition, and athlete health. Yet ironically, the very body tasked with safeguarding these values is itself under scrutiny.

The problem: who pays to police doping?

This month’s announcement that the US Office of National Drug Control Policy has withheld its 2024 payment from WADA highlights the fundamental conflict for WADA.

The US contribution of $US3.6m ($A5.8m) amounts to 13.6% of the budgeted $US26.5m ($A42.7m) from global governments.

WADA’s hybrid public-private structure reflects the balancing act between the national governments on one side and the International Olympic Committee (IOC), representing the sports movement, on the other.

Catherine Ordway, one of the authors here, has long argued the 50-50 funding model between the IOC and the national governments creates “a fox guarding the henhouse” scenario.

This is because WADA relies heavily on funding from stakeholders, some of which have had the highest number of doping cases to investigate, such as Russia, China and the US. This in turn creates serious challenges for WADA in maintaining its own independence and impartiality.

The danger is that WADA could be strong-armed into making decisions to suit major funders: if you are being paid by the organisations that have a vested interest in the outcomes, it could create a fundamental conflict of interest.

The annual contribution due from each national government is proportionate to the size of their elite athlete pool. The IOC pays for the other half of the WADA budget, on behalf of all the international sport federations.

The deficiency in the WADA funding model was exposed during the long and expensive investigation into the “institutionalised manipulation of the doping control process in Russia” following the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympic Games.

Although in financial distress, WADA could hardly beg one of its biggest funders, Russia, for more money to help it unearth the breadth of the fraud.

Instead, it led to WADA seeking private funding for the first time in its history.

A system open to manipulation

The US funding withdrawal is just one example of how WADA’s reliance on national contributions creates vulnerabilities.

This precarious system limits WADA’s ability to enforce anti-doping measures equitably. For example, smaller nations without robust anti-doping infrastructure are more reliant on WADA. Yet reduced funding hampers the organisation’s ability to investigate violations, test athletes, research new ideas, implement education programs effectively, and expand the function of new initiatives, such as athlete Ombuds.

The risks go beyond under-funding. If a government does not pay its contribution, this has a double impact as the withheld amount will not be matched by the IOC.

If other nations follow the US example, WADA’s financial model could collapse entirely. The United Kingdom and EU countries are reportedly being asked to reconsider their financial contributions.

The question is clear: how can we build a funding model that protects WADA’s independence and maintains trust in the system?

Read more:

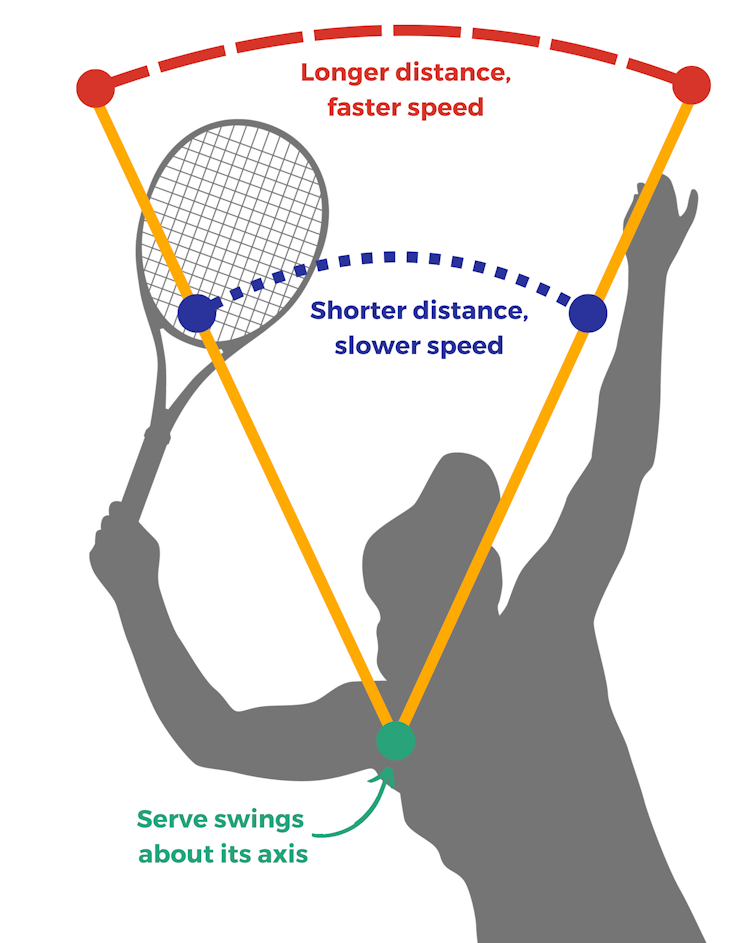

Tennis is facing an existential crisis over doping. How will it respond?

Innovative solutions for clean sport

There is widespread agreement that WADA’s current funding model is flawed. The real challenge lies in designing an a system that guarantees independence while fostering accountability and transparency.

Beyond current WADA efforts to secure private sponsorships, and support from philanthropic foundations, here are our proposals:

1. An independent global trust fund

A neutral, independently managed trust fund could be financed by a small percentage of global sporting revenues, such as broadcasting rights, sponsorship deals, or ticket sales. This would create a more impartial funding base.

2. Expand WADA’s social science research grant program

WADA recognises that social scientists play a crucial role in designing solutions for “wicked” problems, including doping, and has established a social science research grant program to support the science research program.

Rather than limiting research to “athlete behaviours (and) the social and environment factors that influence athlete behaviors”, the grant program could be expanded to look at WADA’s governance, accountability and funding from perspectives including behavioural economics, governance and public policy.

Additionally, social scientists can analyse WADA’s internal structure to identify inefficiencies beyond funding, ensuring anti-doping efforts are as effective as possible.

Since January 2024, Ordway has been a volunteer member of WADA’s social science research expert advisory group, which reviews the grant applications on behalf of WADA. Ordway does not have any research projects that would be eligible for funding under the proposed reforms.

3. Progressive athlete contribution model

Professional athletes could contribute a small levy from their earnings to fund anti-doping efforts. This model would promote athlete “ownership” of clean sport and increase investment in fair play.

However, many player associations argue that until there is revenue sharing (from event broadcasting, ticketing and sponsorship), especially in the Olympic context, and a greater voice for athletes, that this option is a non-starter.

With the WADA code consultation process well underway, for stakeholder approval at the sixth World Conference on Doping in Sport in November 2025, this is the perfect moment to act.

The urgency for change

Without bold reforms, WADA’s credibility and the integrity of sport itself, will remain at risk.

The stakes could not be higher: fair play, athlete safety, and the future of global competition all hang in the balance.

It’s time to take decisive action to remove the fox from the henhouse.

By building a funding model for the future, WADA can be properly resourced to fulfil its mandate as the organisation established to support clean and fair competition.

The future of sport may depend on it.

![]()

Richard Vaughan is an Olympian. He receives funding from Sport Integrity Australia towards his PhD research. He is the Vice-President of the Badminton World Federation (BWF).

Catherine Ordway has advised in anti-doping policy since 1997 and previously worked for Anti-Doping Norway (2001-2005) and the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (2006-2008). Catherine currently serves as a voluntary member of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Social Science Research Expert Advisory Group. She was a member of the WADA Education Outreach team for the Manchester 2002 Commonwealth Games, and the WADA Independent Observer team for the Rio 2007 Pan American Games. The University of Canberra has a Memorandum of Understanding with Sport Integrity Australia, which includes the anti-doping PhD research being conducted by Richard Vaughan. Catherine is Richard’s primary PhD supervisor.

– ref. The US has exposed the World Anti-Doping Agency’s precarious funding model – https://theconversation.com/the-us-has-exposed-the-world-anti-doping-agencys-precarious-funding-model-247442